MATT FREEDMAN

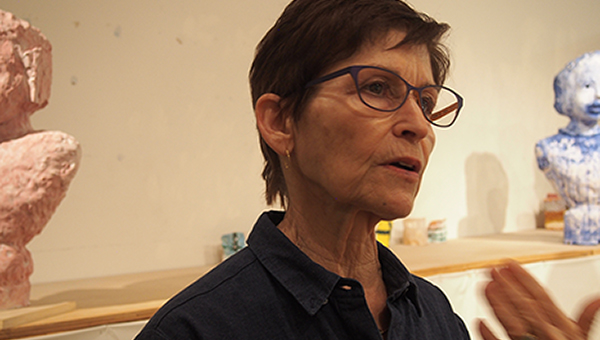

Earth receive an honored guest, our lightening sketch artist is laid to rest. But hey, not so fast. When Matt Freedman died on October 24, 2020 he left behind a studio brimming with artifacts; seems the artist was not quite emptied of his poetry after all.* And that the first image of Freedman’s studio should put one in mind of a still from the closing sequence of Welles’ Citizen Kane settles comfortably if one lets it. Shot from above the image gives us Jude Tallichet, Freedman’s long-term partner, accompanied by friends, all enfolded by the contents of the artist’s studio as they look up toward the craning camera. Seemingly neither the fictional titan of American cinema nor Freedman ever threw anything away.

Matt Freedman’s studio from above with half of the storage boxes opened, cleaned and sorted — ready to archive.

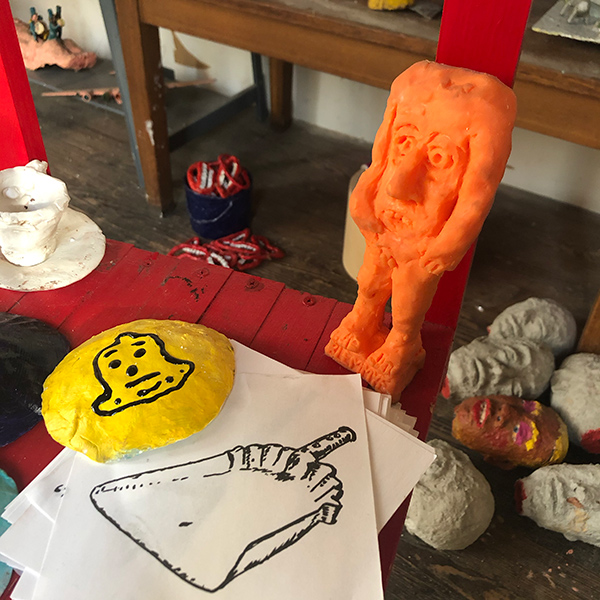

Beginning in January, 2021 we made a series of virtual trips to Freedman’s studio. Tallichet was the guide. On her phone she tracked a video visit through the work-crowded space. Pausing as an object seized the attention of any one of us. The feel of the visit was —as one might expect— not exactly celebratory and not exactly mournful. Extemporaneous associations sprang up in attempts to figure out, or simply remember Freedman’s intent from object to object and piece to piece.

Golem

As we toured, as sightings of remembered pieces accumulated, and absent a starting point identified by Freedman it seemed that a useful place to start thinking about the work he had left in the studio was a show from 2012. That year Freedman mounted a show at Valentine Projects in Ridgewood. Like much of Freedman’s work the show in question relied upon a swirl of research that threaded histories into and around one another and montaged disparate cultural spaces into dialectical collisions. The show’s theme looped around the history of where the artist and his partner lived, a former synagogue in Queens, New York (the very space we were virtually visiting). It feels somewhat contrary to Freedman’s mode of work to identify a ‘center’ to such a project –again the centrifugal swirl of information is the texture of the work– but if The Golem of Ridgewood, as the show was titled, can be seen as possessing a focal point it would be the eponymous film that was screened at Valentine and now has a permanent home on Vimeo.

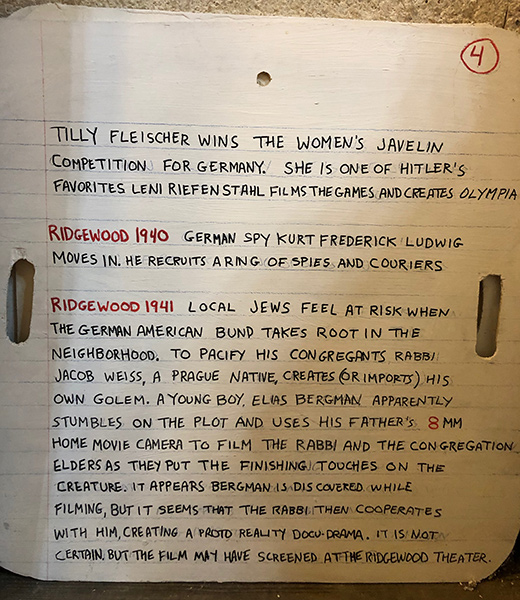

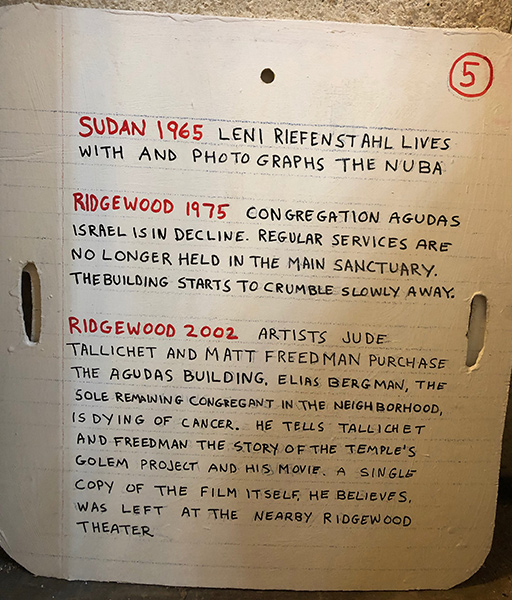

To get a fuller sense of the churn of the references and furrows the show engaged with, one could note that the timeline Freedman situated the film within begins “Eden−6000 BCE: G-d fashions Adam from the dust of the ground, and animates him.” And ends, in as much as it does so, somewhere around, “Ridgewood, Queens−2008-2011: Guided by clues in what remains of the film, Freedman and Tallichet recover parts of the lost golem.”

The conceit subtending both the film and the gallery installation is that, circa 1930s into the 40s the pro-Nazi, German-American Bund is establishing a presence in the Ridgewood section of Queens, New York. Thus, but let us have Freedman’s own words fill us in . . .

Local Jews feel at risk as the German-American Bund takes root in the area. To reassure his flock, Rabbi Weiss creates his golem. A young congregant, Elias Bergman, stumbles on the plot and uses his father’s 8mm home movie camera to film the rabbi and the congregation elders as they put the finishing touches on the creature. . . . From the surviving footage, it appears that the boy is discovered while filming. Perhaps considering the uses of newsreels as propaganda, and presaging the role of moving-image documentary in disseminating information about the death camps, the rabbi then allows him to film openly.

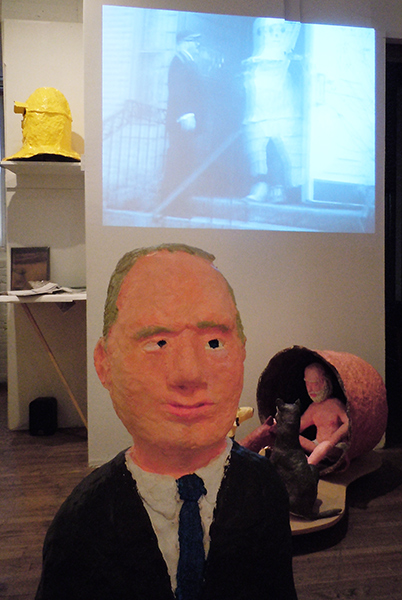

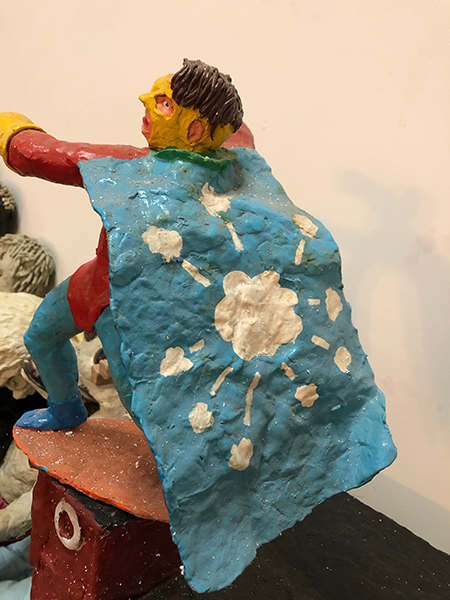

As Freedman’s narrative has it, using an extant remnant of that film he and Tallichet are able to recover fragments of the creature itself, fragments that have been dispersed and concealed throughout the synagogue that Freedman and Tallichet now call home. The golem’s sword is found in an out-building, the head and its accompanying helmet had been secreted in the building’s attic space, in the garden they dig up the left hand, and on and on, until the whole morselized creature is fit to be reassembled. And in the show at Valentine the creature was there, standing tall (minus hands) sharing space with, half scale figures representing the important historical moments that intersect Freedman’s timeline. Now, in a recursive move, the golem and its armor have returned to the synagogue where they were conceived.

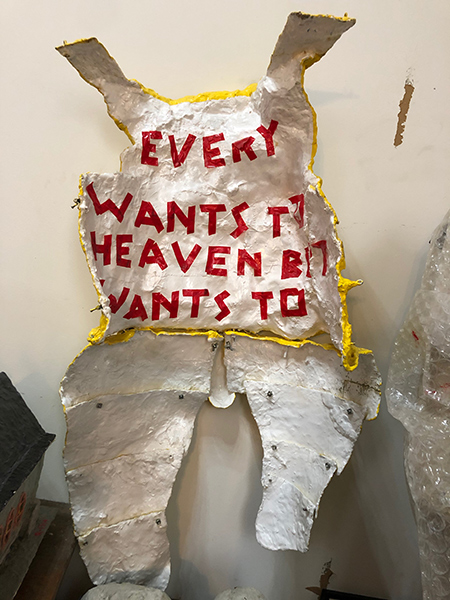

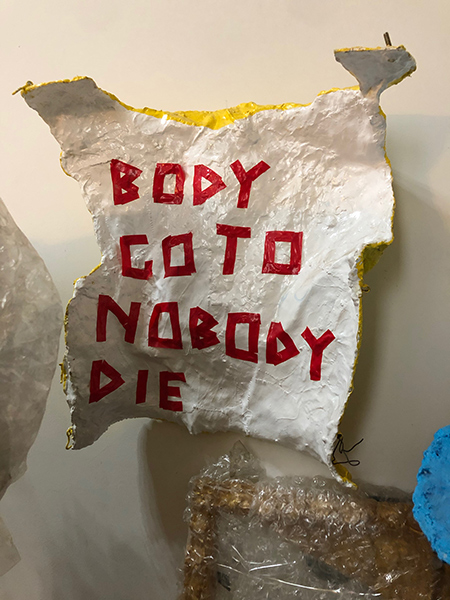

No longer lost, the golem bides its time in Freedman’s studio. It is now disassembled, again, into its various parts and there it ‘lives’ along with the remains of the other artifacts that he produced for the show. The golem’s tortured poignancy signals immediately and resiliently, as Tallichet’s camera tracks through the space. For the show at Valentine the golem was naked, shorn of its armor. Here, in the studio, it is reunited with that armor. It is armor that is painted bright, bright yellow on its outside and set casually leaning against the studio wall. Set in that manor it now reveals the more subdued, dully painted inside that an audience would normally not see. Thus within, nominally invisible and unbeknownst to the viewer in a normal setting, a legend is inscribed by hand in bright red paint, it reads “everybody wants to go to heaven, but nobody wants to die”. Freedman’s golem knew irony.

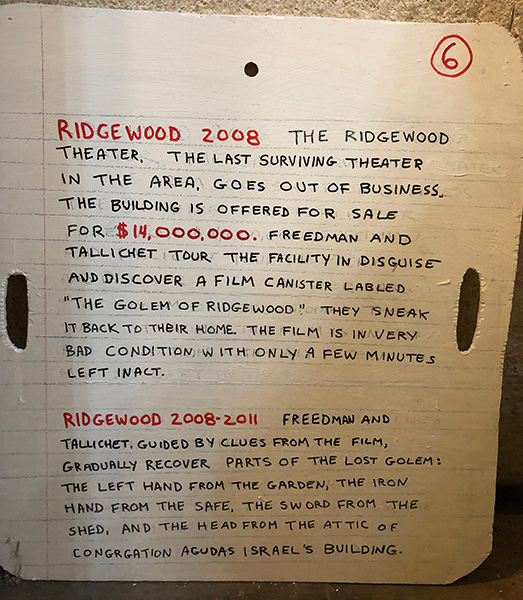

Stacked against that same wall rests a series of hand painted reproductions of notebook pages. In the show, The Golem of Ridgewood, these paintings functioned as, more or less, wall labels for the show. They, more or less, guided the viewer in their understanding of the assembled artifacts. And it is a case of more or less because in these notebook pages Freedman circumnavigates the solar system. He does this not because he is lost, but because there are so many important and captivating things in the solar system that will lead us to encounter the golem exactly where he wants us to. Thus, in this journey, Berlin, the Olympics of 1936, collides with Troy in 1183 BCE where Petroclus wearing Achilles’ armor slays 47 Trojans, then on to Prague 1550 where Rabbi Judah Leow creates the original golem that, according to legend, also wore Achilles’ armor. Next, to Rochester, New York 1932 where the standard-8 movie camera is released for home use which then allowed Elias Bergman to film the golem of Ridgewood in the first place. Which in turn allowed Freedman and Tallichet, in Ridgewood 2008, to find a copy of that film at the soon to be demolished, last remaining theater in Ridgewood. And so it is also important to know, per the history of Ridgewood, that Diogenes is not only a Brewery founded in Ridgewood, Queens by German immigrants who worshiped at the nearby apostolic church, built in 1910 but sold in 1914 to Jewish merchants who founded congregation Agudas Israel, aka the building where Freedman’s golem now resides.

But Diogenes was also a founder of cynic philosophy who, reputedly, made common cause with dogs rather than humans and mimicked dog behavior. Thus he, Diogenes, made the cut and was in the show at Valentine surrounded by a pack of dogs. In the studio, now, Freedman’s model of the Diogenes Brewery shares table-top space with his model of the synagogue itself –both in the Valentine show. While high up on a top shelf, now seen from a Dutch angle she would probably have endorsed, is a half scale figure of Leni Riefenstahl, filmmaker-witness-semi author of Hitler’s 1936 Berlin Olympics. And, if she could tilt her camera down a notch and pan to the left, she would catch a shot of the golem’s armor open to reveal its ironic inscription.

For the show itself, at Valentine Projects, the viewer processed through the space, somewhat like a museum and, diligently paying attention to the wall texts, the inventory of the show could be digested less pell-mell than in the studio. The poster for the show itself, an image of the creature’s helmet prefigured the actual helmet, shown at a slightly higher plane in the gallery’s sign-in area. Processing past this, the golem’s shoes were to the left, whereafter one found oneself facing the film fragment itself projected onto the gallery wall. Grainy and streaky it evoked its history of loss and recovery. And then at a turn away from the film, passing Leni Riefenstahl with camera at the ready, one faced not the golem itself, rather one found oneself face to face with a comic foreground; one of those images of a body with a hole cut out to put your own head through (which Freedman was so fond of [see below]). Put your head through the hole and for $3.00 you could walk away with a polaroid of yourself as the golem throttling Hitler and Mussolini. For Freedman the sense of carnival, the feel of the midway and vaudeville were never far away.

In its way the studio, as left by Freedman is an allegorical memorial to the way his thinking -and practice- as an artist worked. We could think of The Golem of Ridgewood as a frame story that leads us to all the other stories that are the content of his studio. All the side turns and major arteries of his thinking and practice as an artist, writer, curator are there. The studio, as he left it, has the feel of the intellectual churn that drove him and it does not feel as if it is going to settle down quietly or quickly, (it needs a show). The history of his work and his preoccupations flicker and hail from the various groupings in the space.

It is worth noting that there are non-golem figures in the studio, too. Avatars of Freedman himself in some instances. Freedman’s own self-declared avatar holds a commanding presence in the studio. It is tall and silver, it is topped by something resembling a giant topknot of orange-yellow hair, It’s mouth is gaping and scarlet, its posture lumpen, top heavy and ungainly as if it might topple. It stares or glares across the studio at a pair of bobble-head sculptures of Freedman that relay a flatteringly handsome image of the artist. These handsome heads, cast from a model of Freedman crafted by artist Lisa Levy, bob around on bodies modeled on the biblical beggar Lazarus, sores and all, while simultaneously reminding one of the kitsch, bobble-head mementos of sports teams. And, that there are two bobble heads points us toward his work as a curator.

Twin Twin

Twin-twin, a series of group-shows about or in memoriam to the twin towers pops up frequently. Those shows, and the train of Freedman’s thought –puzzling through, trying to find a way to speak to the trauma that they represent– emerge in squirreled away pieces throughout the studio. It was never the relatively straightforward geopolitics of why 9/11 happened that fascinated Freedman, but somehow the twinness of the towers took on an extra weight after the attack. The image of the towers as twins becomes all but an occult symbol. In the crowded group shows Freedman organized around this theme, the twin motif emerged unbidden in pairs of clocks, doubled models of The Empire State Building, facial hair shaved to represent the towers, twinned gumball dispensers, a double stack of bureaucracy as represented by banker’s boxes. There was a hammer with the twin towers modeled upon its shaft, as if a spontaneous growth to memorialize the event. The associations of the many artists Freedman invited to participate ranged widely, indeed encyclopedically. In the studio Freedman’s own fascination with the motif ricochets around the space. An oval, ornately framed print, that just might be a reproduction of a Fragonard, is repurposed by Freedman as an 18th century Rococo rendering of the towers on fire. It casually leans against a flat-file, beside it sits a thrift store painting similarly adjusted. His own preoccupation with model aircraft, a passion since childhood, collides with the 9/11 events; on a lower shelf where a plastic model kit of a plane is almost invisible one notices that the twin towers protrude from atop its cabin. Or, greedier for space and out in the open, a large white wedding cake appears. At first it had seemed that the wedding cake’s tiered layers must be derived from paintings we have seen of the tower of Babel –Verhaecht or Bruegel. Yet in Tallichet’s recall the cake followed on from the twin-twin shows, atop the cake are the twins, the joined couple, antithesis of Babel. And yet those tiered layers still do seem to rise akin to a ramp. In the end, in a Babel-like way, the twin-twin shows were about everyone trying to say something about the same thing, but saying it differently.

Endless Broken Time

And then there is the non-studio, or the studio that Freedman brought out into the world in his performance series with Tim Spelios: Endless Broken Time. In these performances Freedman’s prep and presentation had the same stone skipping energy as the narrative of his Golem show. This time the show was a montage of words, percussive beats, drawings, drum solos and the artists’ bodies present before the audience. In its entirety the piece demonstrated that the literary space that makes most sense in Freedman’s world is the encyclopedia.

Endless Broken Time was a series of more than 50 performances presented between 2015 and 2020 usually at Studio 10 in Bushwick, Brooklyn. In a recurring, but subtly shifting over time, presentation, Freedman performed as a lightning sketch artist, while Spelios marked the tempo, and underscored the verbal presentation with his percussive accompaniment. On occasion Freedman would accessorize his appearance with a hat or exceptional shoes, but mostly he stood before the audience casually attired in street clothing, while Spelios sat adjacent to him at the drum kit. Standing erect in the fore of the usually compressed performance space, large pad of paper dangling around his neck, Freedman would illuminate with charcoal drawings –executed upside down– the layered material that he ruminated upon, connecting dots to breadcrumb trails that led down rabbit holes of awe inspiring clusters of humor and all-encompassing knowledge. As each drawing was executed, and as the next idea was ready to be illustrated, a sheet of paper was torn from the pad. Forty-five to sixty minutes in, the entire performance space was strewn with discarded drawings. The topic might begin with autobiography, the house Freedman grew up in Chicago say, but pretty soon he found a way to align corrupt Chicago politics in there. Thus, big picture and small picture were sat side by side, allowing Freedman to offer himself as a connoisseur of unexpected connections.

Inevitably Freedman managed to bring cultural history and idiosyncratic memory into the monologue. Not infrequently this would mean reminding us of the persistent appeal of some element of kitsch that we had either forgotten or never actually known –Cassius Marcellus Coolidge the self-taught artist who patented comic foregrounds, again, those images of a body with a hole cut out to put your head through, like the one used in the Golem show– would be a concise example. For Freedman the twist he offered to this was that the drawing dangling around his neck became a comic foreground that he could then yank upward to place his own face within the drawing, turning himself momentarily into a mermaid or a fisherman.

In these varied ways knowledge, memory and intellection became vaudevillian spectacle. While the bigger point was that knowledge itself, and not just in the internet age, is a labyrinth of repeatedly intersecting vectors that can be endlessly adjusted depending upon the most recent collision of, well, memory. It was all a bit like the endless broken time of clinical psychoanalysis. (And, perhaps relevantly, perhaps not, Freedman’s father was a Freudian psychoanalyst.)

The performances of Endless Broken Time have been archived: https://www.endlessbrokentime.org/

Tim Spelios maintains an Instagram account that extends the project: https://www.instagram.com/endlessbrokentime/?hl=en

Monsters

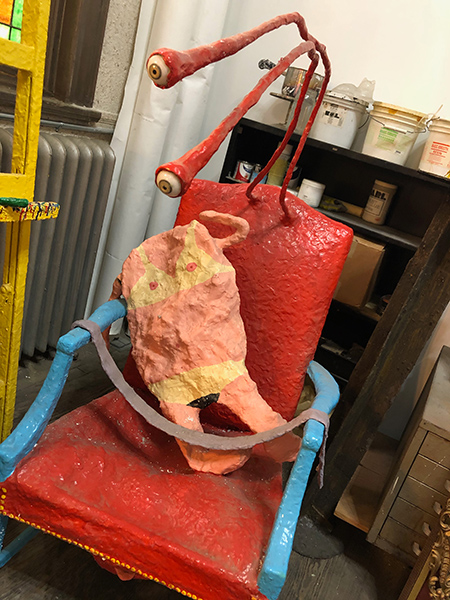

Meanwhile back in the studio itself the monsters are waiting. Some are comic, the “Low Monster” is low, close to the ground, and has LOW painted across its back. The picnic monster contains cups and a blanket. These are monsters that kids could love, and this is art that includes ‘jokes’ in its list of media. Even though, generally speaking, not a lot of space is allowed for outright jokes in serious art unless they are rebranded as subversive or ironic humor. So, as much as the Golem show toyed with the conceits of a museological project, and Endless Broken Time mined the traditions of vaudeville –illustrated lectures, lightning sketch acts– this suite of monsters, including the “Low Monster” and the “Picnic Monster” court Freedman’s long relationship to cartooning. Freedman had first worked as a cartoonist way back in Chicago in the 1980s and he stayed connected to it as mode of presenting ideas and narratives all the way through in his journals, including the published journal of his illness, Indolent but Relentless (2008). But here, now, in the studio, the cartoon rhetoric achieves three dimensions. Plaintive facial expressions –sad, sad eyes– inhabit the dimensional space that we inhabit. The funnies have come, not quite to life.

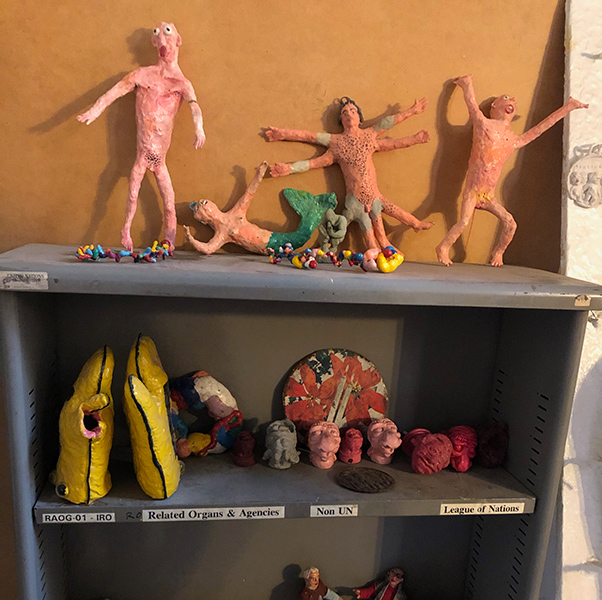

These monsters are very clearly un-golem, as in no supernatural act or incantation is going to animate them. They are fabricated from hard plastic, epoxy, implanted with taxidermist’s eyes and painted in bright enamels, gloss color unspools in and on them. Posed as on-the-move they remain cruelly static, paralyzed, even as one extends one’s empathic gaze. They are exiles from a landscape of cuteness that they nonetheless invoke. They are the sculptor’s version of God making things, no actual magic, just hard work. (It is important to remind ourselves that Freedman was, on top of everything else, a figurative sculptor.) Historically, they stem from the Clumpism show of Freedman and Paul Rhoades. Clumpism, being a comedy act –you could call it a cartoon– art movement spoofing the -isms of modernist art history that Freedman and Rhoads concocted. It ran with the tradition of much of the historical avant-gardes in that its posture was oppositional and bratty, allegedly beginning with a staged fight in 1979 at a Leo Castelli opening. The video of Freedman touring the pre-opening at LIU gallery in the 2009 Clumpism show sets the tone of erudition and entertainment melding their project.

Another tranche of monsters eschews the enamel paint but doubles up on the taxidermist’s props. The realistic yet artificial eyes and teeth redouble their power by being combined with thrift store, hand me down clothing, the shiny and the tawdry shake hands. These monsters are cadaverous and crepuscular. Sometimes they are watchful –through distended eyes. In one particularly disturbing case a monster-child, as signaled by its garment, has for facial features –surfacing again like an OCD intrusive symptom– the twin towers. These all are of a more recent vintage and one could readily think of them as try outs for the golem’s helpers. But if a golem is modeled on human form, brought almost to human life, these creatures are more of hybrid. They are perhaps humans shape-shifting with another animal form. As such they constitute a bestiary where each figure bears some ambiguous allegorical lode. Some are companion animals, dogs. At a turn they can also seem very undomesticated, wolves. The taxidermized elements, the teeth, the eyes, speak of a state beyond life, as if they, like us, know about death. In the studio, now shorn of original or intended exhibition context, they are like a group of Freedman’s studio-friends; his own delectable creatures. So, if a golem is of the earth, if it becomes live as flesh, Frankenstein-like, while an avatar is –in a pre-gamer world at least – ethereal, perfect, of the heavens. These guys can’t make up their minds, they don’t know which way to turn. Their home might be, probably is, a child’s dream landscape.

Perhaps Auden can help us here –as he did in the opening paragraph of this essay with a line from his In Memoriam to W.B. Yeats– this time with his other magisterial, memorial poem to, who else? Freud of course:

. . . he would have us remember most of all

to be enthusiastic over the night,

not only for the sense of wonder

it alone has to offer, but also

because it needs our love. With large sad eyes

its delectable creatures look up and beg

us dumbly to ask them to follow:

they are exiles who long for the future

Now, longing for the future becomes the saddest of problems.

Matt Freedman died October 24, 2020. Now time seems truly broken.