Lenore Malen

New York City, Central Park. Four animals, a horse, a goat, a lion and perhaps a Dalmatian, make their way as a team, seeming to rappel without ropes, across a rocky outcrop of 450 million year old schist rock. The blocking of the figures evokes the dance of death scene from Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. The pinstripe skyscrapers in rear bring to mind Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. The setting, Central Park, deploys, tragically, Olmsted’s culture performed as nature. We would do well to remember that Bergman staged his opus as a chess game between a returning crusader and the figure of Death as the bubonic plague ravaged Europe; that Hitchcock invented for his film a compass point that simply does not exist, while, with Olmstead, nature is nothing more than an echo of an anthropomorphized projection. As we sift and connect these dots, as we do for the above the very messy calculus we all know this will not turn out well. An end game is in at hand.

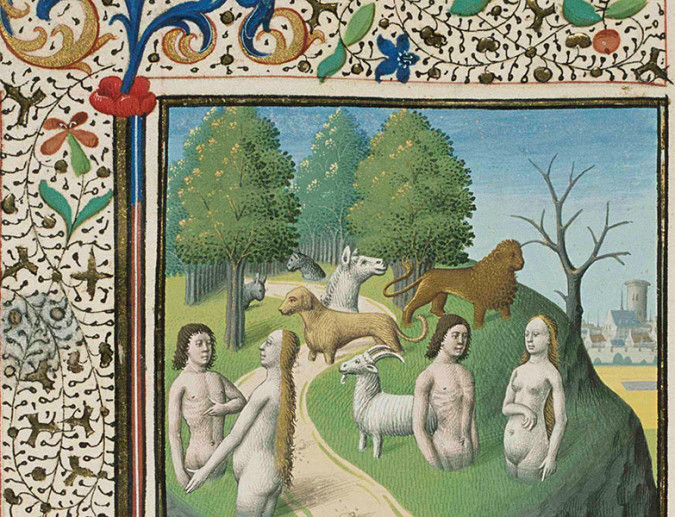

Approached in medias res in the studio this is an initial take on Lenore Malen’s current project, a multi layered and multi part film project titled Scenes From Paradise. Screened for us by the artist in her studio, provisionally arranged as a three-monitor installation, the work unconsciously, unknowingly, came to resemble the three altars of a place of Catholic worship. (Maybe prayer can save us, but we have our doubts.) The entire project has evolved over the past two and a half years out of Malen’s chance discovery, as she browsed the web, of a medieval manuscript illumination. The artist of that illumination, The Maître Francois, worked in the service of The Duke of Nemours, producing the rarified knowledge of the less literate, but in its own way knowledge filled, 15th century.

The Illumination Francois produced inscribed knowledge for his patron with a tale of beginnings. It reveals autochthonous creatures, four humans and six other animals, birthed from the substance of the earth itself. And though the landscape looks rather prim one must suppose that this is the famous primordial muck from which animal life comes into being. That there is no immediate or apparent hand of God visible in the image seems important, even though ones atheistic joy must be tempered somewhat by the recognition that in the next ‘frame’ the devil is present thus implying his manicheistic opposite. Nonetheless the democratic (sic) emerging of all the animals, human and non human, from the muck does allow one to ponder in whose image is whom being made and for that matter, by whom in this pristine paradise. In Malen’s project she acknowledges that the narrative destination is the time before The Maître Francois’ illumination, the time before Eden. Malen will, in Scenes from Paradise, narratively, return Adam, Eve and the menagerie spied in Central Park to the pre-pre lapsarian, primordial muck. It has the feel of a last chance gambit.

Malen has before now seized upon the look and feel of utopian and dystopian communities. In the late 1990s she conjured up the New Society for Universal Harmony from the Eighteenth Century ruins of Franz Mesmer’s original Société de l’harmonie universelle. Mesmer’s original society sought to explore and promote Animal Magnetism, an intangible and mysterious force said to influence human beings and deployed by Mesmer in his treatment of patients. In Malen’s reincarnation the society took the shape of a secular community made available to the viewer through documents and recordings of simulated clinical encounters. These were delivered to the audience by a series of performers and performances realized through photography and installation. In 2005 the project culminated in an eponymously titled book to “archive” Malen’s reinvented society. Therein there was much evidence of the beguiling apparatus of treatment and arcanely posed patients. The tenor was of mysterious alchemical science. The whole hummed with a notion of redemption through community while visually the echo was of Charcot’s photo documentation of his Salpêtrière patients.

Later in the 2000s Malen turned her focus to beekeeping producing a body of work under the heading I am the Animal. Contra reinventing a collapsed micro-culture, as in the New Society for Universal Harmony, Malen in I Am The Animal wormed her way into an existing subculture of beekeepers and ultimately into the culture of bees. Malen learned to be a beekeeper. She tended her hives and communed with other beekeepers in the Hudson valley region of New York. Malen spent a great deal of time observing hive behaviors and hive culture. In Malen’s own words, from an interview with Amy Schlegel on the occasion of her show at Tufts University Art Gallery, “You could call I Am The Animal an attempt at a reverse anthropomorphism, re-imagining human culture as a hive, if that were even possible.” Initially Malen produced a 22- minute documentary about the beekeepers in the Hudson Valley. Later the work spooled on into a broadly immersive video installation promulgating the undoing of anthropocentrism. In many ways these two earlier projects presage the network of concerns approached by Malen in her current Scenes from Paradise.

It is of course the case that in the studio one encounters work in ways particular to that setting. Work remains unfinished. Work is not necessarily presented in the final planned order, if such exists. Work is offered as in process, still evolving. Currently Scenes from Paradise exists in six or perhaps seven parts. These parts have various relations of dependence and independence from one another and how and in what conjunctions they will be screened is at this point a fairly open question. One of our first memories of this project in the studio is of Reversal. Reversal is one of the segments, a video, realized like many another video, through recorded images and synchronous recorded human voice. However, in Reversal, the transparency implied in that pedestrian description of video is in short order conjured into an entropic collapse of politics, meaning making and borderline territories between species, classes and cultures.

The voice in Reversal is a speech rather than a conversation. It is a monologue delivered in a sort of Pig Latin. Though more really it is like hyper-speed English back-slang, wherein the entire text is delivered in reverse, thus emphasizing the normally invisible coded nature of language. Both back-slang and the speech in Reversal bring to the fore codes that exclude and promote boundaries. They create insiders and outsiders, boundaries where permeability and impenetrability dial back and forth. And in this body of work it is boundaries between species, and the way such boundaries are engaged, that preoccupy Malen. Overall, the images of Scenes from Paradise flare up with and continuously replay humans mediating animals. Humans dress up as animals, they mimic animals, they image animals on phones and pads and in costumes. And in Reversal the central performer both dresses as an animal –more or less– and speaks the speech Malen imagines animals might need to deliver.

Unintelligible in the extreme the speech in Reversal is, nonetheless, transfixing, offering a meaningless erotics of human-ish, animal-ish sound. It is somewhat like grunting toward or at ones pet or infant for an extended period of time, and it is all transcribed for us as scrolling English language subtitles across the trinity of screens form right to left. (Above is a single channel extract.) And, though the text is not itself in reverse, its reverse movement from right to left catches one off guard. It places one in a haltingly unfamiliar proximity with ones own process of reading and making sense. On the center screen is the performer delivering the monologue. She wears a headpiece, come BDSM prop, made from bright red rope while her garments are white. To the screen on her right a medium-shot is held on one of the carriage horses that transit tourists around and through Central Park. The white horses’ bridle strongly resembles the speaker’s headwear. To the speakers left, a montage unravels. There are carnival scenes of stuffed toy animals and bouncing inflated ones. There are images recorded at the butchers –meat galore. And there are outtakes from the Soviet space program, grainy footage of Laika spinning into zero gravity. The conceit that informs Reversal is that the speaker is a horse from the 15th Century manuscript culled by Malen from her web browsing. The speaker is animal-kind’s representative declaiming a list of atrocities perpetrated against non-human animals by humankind. The text of the speech borrows from, and parodies, the speech delivered by Dilma Rouseff in 2013 at the United Nations General Assembly. It is the speech where Rouseff famously, notoriously denounces the United States for spying on its allies and friends in the wake of Edward Snowden’s revelations. A contemporary politics of betrayal is sketched out by Rouseff’s backwards/forwards speech and, to be sure, by the luminous emotional charge of the location where it is given: the United Nations General Assembly. (A location used, COINCIDENTALY (?), by Hitchcock in North by Northwest for a famous backstabbing scene.) In the end, with Reversal, what some humans do to some other humans is a placeholder for a historical litany of inter-species destruction and domination.

So can animals and humans speak to one another? Yes obviously is the answer, but the question put thusly belies the complexity of notions like speech and “one another”. Clearly Reversal’s horse has much to say to humankind and if we pay attention to the scrolling transcript we might get the message. Jean Cocteau, a fan of reverse action in his films, certainly thought that the estranging effect of revealing things in reverse would force the viewer to know them better because of their unfamiliarity backwards. Malen amplifies the estrangement by reversing the audio track instead of the image. In watching her bees, and in reading about research on bee culture, Malen came up with no definitive answer about who gets to speak to whom and who might understand whom. But the question itself of the distinction –human to animal– comes to seem built on shaky ideological and metaphysical grounds. Invoking Giorgio Agamben Malen describes for Amy Schlegel how we modern humans animalize certain parts of human life and define what is human as that which cannot be animalized. “Such exclusions allow us to create a non-human human, a monstrosity that we are allowed to do anything with. This made possible the concentration camps, and now Guantanamo.” For Malen, in Reversal, obscuring and reversing meaning, makes meaning making much meatier. Much more hangs on the bone than simple riddles to solve.

* * *

Back in New York’s Central park those animals from the manuscript illumination are still making their way across Umpire Rock. These animals as we have called them, as viewers will see them, are of course actors, actors clad in cheap, kitschy one piece suits –like down at the heels astronauts. Of the four characters two are in bright pink suites and two are in yet brighter yellow ones. We know they are animals because each human face is concealed by a cheap, plastic party-store animal mask. These four plastic faced bipeds are Malen’s gloss on aboriginal beings caught at the Ur moment of existence as they issue directly from the earth. In this sequence, subtitled The Reason Of The Strongest Is Always The Best, Malen directs her actors’ slow passage across the giant rock. New York skyscrapers foreclose the proscenium’s rear, dappling the rock with shadow and glare while the animals tread with a cautious if not awkward gait. It is the natural caution of animals one might suppose. But it is also the caution of one who is not comfortably from here. One who does not belong in this place. And the place, the place that this is, is one can think, key to the whole project of Malen’s. It is a question of place that shapes and haunts each separate video component and the total assemblage of Scenes From Paradise. It is the sense that there is no place of return. No route back to the pre-lapsarian. The lost animals are only awash in a list, a scattershot, of cultural references. They turn a corner from one enacted cultural scene to the next and so on until, ominously, curtain call. The mini-references are peppered throughout. Already checked off are Hitchcock, Olmsted and Bergman. On screen Rafael Viñoly’s towering 432 Park Avenue looms above the park and the animals. Designed around what is described by Viñoly as “the purest geometric form: the square, and inspired by a trash can.” The building’s street address says to New Yorkers as much as they need to know, while the wealth-scale of entré to said address will be anything but hidden by its shadow profile. Like a sundial counting down to midnight, Viñoly’s shadow will chase the animals out of Olmsted’s phony Eden.

* * *

Malen trawls wide culturally. In another of her Scenes From Paradise Malen borrows her title, Four Saints in Three Acts, from early Twentieth Century, dramatic modernism. Malen’s take upon Virgil Thompson and Gertrude Stein’s opera is played out on the rooftops of Long Island City. In the background the Long Island Expressway plunges into the Midtown Tunnel (or read the other way –left to right– the tunnel spits out Wall Street parasites on their Friday afternoon ride to the Hamptons) as Thompson and Stein’s opera resounds to the challenging sound of the 7 train atop what used to be the factory buildings of New York’s manufacturing base. That such Bohemian modernists as Thomson and Stein have always played in proximity to the masters of ‘finance’ may not be Malen’s point but it is a fact that should surely not be lost sight of. First staged by Chick Austin at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford Connecticut Four Saints in Three Acts was an important element in the cementing of American Modernism and elite patronage. Austen’s influence upon the development of Modernist practices in theater, dance and fine art reticulates across the urban landscape from Harvard and Hartford to Park Avenue. So yes Thomson and Stein supervised a clash of classes with Austen’s patronage and the induction of plebian instruments into the orchestra. But Malen’s setting ramps up the clash while drawing class, willy nilly, along into the territory of the latest war of social survival in the urban rubble of the anthropocene. For Malen the opera is delivered in a voice over recording while a lone player, dancing across the rooftop, voices a solo rendering of the signature line of the opera, “there can be no peace on earth with calm”. The actor is positioned at screen left, while a visual counterpoint of a giant electronic billboard, hovering above the tunnel entrance/exit, blinks relentlessly at screen right, as it peddles “All Natural Chobani yogurt”. Thence, surely, the circle closes around any and all nature culture dialogues.

It is in Chobani sponsored ‘natural’ moments like this, as the Wall Street rich speed through the morass of Long Island’s one hundred and eighteen mile suburban blight toward their manicured Hampton’s nature, tended by undocumented Latinos, who are hated by their unemployed white working class neighbors who are relentlessly told they are middle class people, that the full mien of Malen’s layered cultural and political project unfolds. As Malen observes, speaking of her earlier project, I Am The Animal, ‘the real subject of the film is the breakdown of boundaries between human and animal, organic and inorganic, the biological and the technical that leads to the realization that “there is no human and there never has been” and that “the human is not a given but rather is made in an ongoing process of technological and anthropological evolution”. For Scenes From Paradise we must surely add that political and urban evolution specifically of New York City are also important terms of that human-making equation. Malen is herself quoting Cary Wolfe as she recognizes that there are no sustainable boundaries. Boundaries are, rather, a magic confection born of ideological needs that have by now worn thin. Thus there is no returned-to-nature to be pulled, rabbit like, from a hat or a political movement. It –nature– has been changed utterly. (We are still awaiting the terrible beauty??)

* * *

In what might be the concluding chapter of Malen’s project Adam and Eve make their first entry into Scenes from Paradise. The Ur protagonists of human history can be found on a sheep farm near Ghent, New York, which stands in amply for Eden. The two proto-humans wear wonderful full-frontal nude suites that, with deft modesty/censorship, display the humans’ un-embarrassment with their ‘natural’ bodies. The other animals, from the original 15th Century Illumination, are also there in the guise of a small flock of gamboling grey sheep with whom Adam and Eve interact. As Malen muses of Adam and Eve in this sequence “They learn to be human going about it naively, . . . they interact with the sheep. They react to objects, . . . they sit and talk. . . . they name the animals. They die.” It is a closed system of no hope.

That Scenes From Paradise is overwhelmingly about a complexly shaded eco-catastrophe is a given that is ever present on Malen’s screen. That a class driven, economics driven, north-south divide driven potlatch has been played out is a given. And potlatch has always had the risk, the catch, (its given), built into it, that is, you might just give too much away.

Again, no rabbit from hat, rather there is a need to reinvent what we mean by and use as nature going forth. That the style of Malen’s intervention has a Planet of The Apes feel to it (perhaps it is the down at heals astronaut’s suites) is no coincidence. Knowing, understanding the nature/culture toggle switch plays out on precisely the cultural terrain where images come to represent lived experience is the key. And so sitting in Malen’s studio, watching Scenes from Paradise, we became aware of the reflections of the video images on the studio floor. They conjured up a flickering afterimage of nature, nature not quite lost. But also they brought to mind human optics. The image on the floor was, after all, upside down. Like the image on the human Iris before all that heavy lifting, brainwork is done to turn it right side up. The suitably confusing question, then, might be, what work is to be done turning what which way up?

More of Lenore Malen’s work can be seen at: http://lenoremalenblog.com/

Fantastic piece….I am reviewing her for the Brooklyn Rail and only wish my review was a brilliant as yours….congrats……