Jill Moser

“Poetry should be one of our “Human Rights”

. . . its subversive: subversive and vital.” Roland Barthes

As Jill Moser recounts it, one of her early exposures to contemporary art as a young adult was trekking into New York from the near suburbs to watch films at Anthology Film Archives. “Michael Snow, Brakhage, Maya Derren . . . Jonas Mekas was my hero.” It is, of course, a list of names that we now acknowledge as the cannon of American independent filmmaking. It is a list that outlines the formulation of a cinematic practice of lyrical form, an elision of narrative and the explosive presence of abstraction. To have watched these films is to have been immersed in the mid to late twentieth century poetics of cinema.

It was this exposure to such cinema that Moser credits with leading her toward her painting practice. It was, for her, a cinema that counseled a “meditative way of looking that is non-narrative.” It was a cinema that induced “an evocative experience of looking that was without language.” For Moser this cinema evinced a range of subversive and vital strategies for deploying and experiencing visual signs. And it stands as a testament to an ongoing engagement by such cinema, very much shared by Moser, with the wily ways of meaning making where the visual and linguistic collide.

Thus it feels somewhat ironic, or important, or relevant or all of the above, that before art school, that is before an MFA, Moser studied semiotics at Brown. This was the 1970s, a particular historical juncture, where semiotics was as a virus in some quarters of the American academy. An import, a ‘French’ notion that nuzzled up to language and linguistics, to the study of cinema, to the writing of history, to the practice of psychoanalysis and shuffled them all around outing the sign, the word, the utterance, the shot, the mark as not transparent, givens but as sites of contested possibilities drenched in unending layers of connotation. It is this particular filtering of language and sign making that shaped Moser’s early work. And language, as writing, as graphic icon, as bearer of meaning, as a bundle of loose lipped conventions we all share and trade in has always, and continues to be a model in Moser’s work.

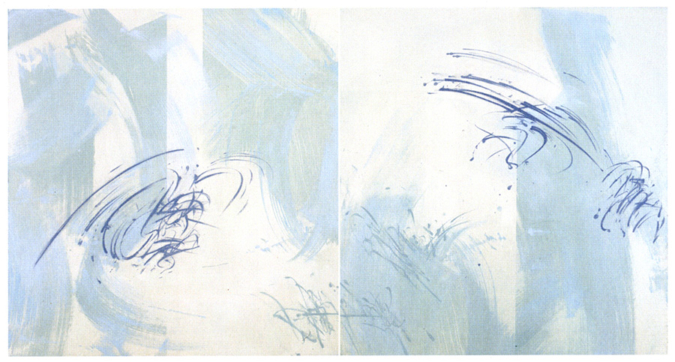

Naming Game

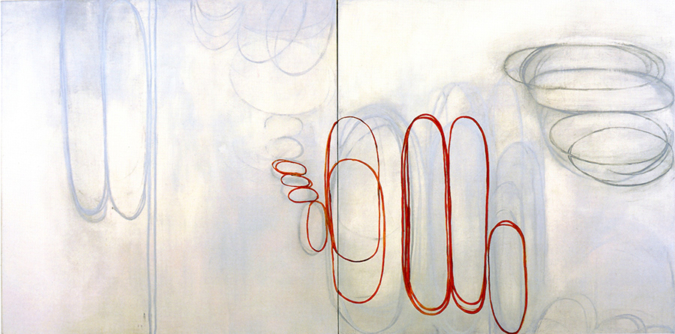

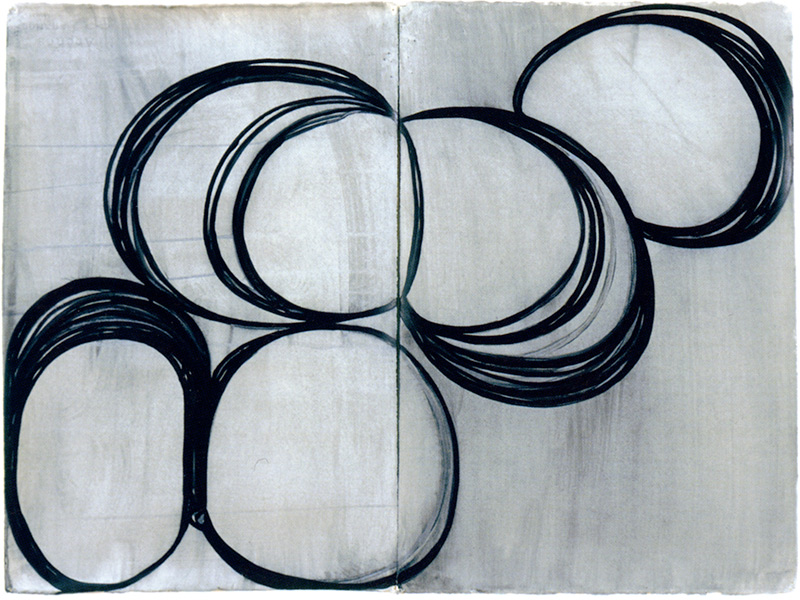

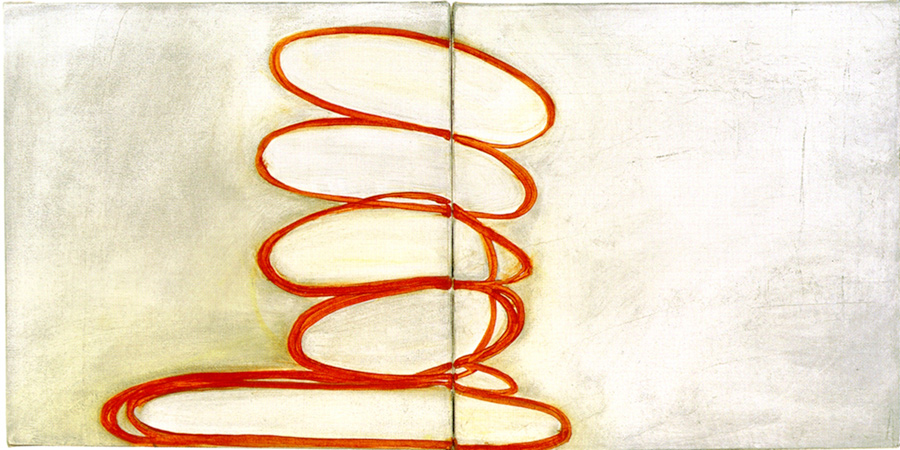

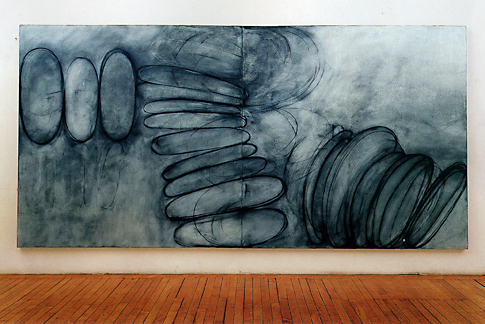

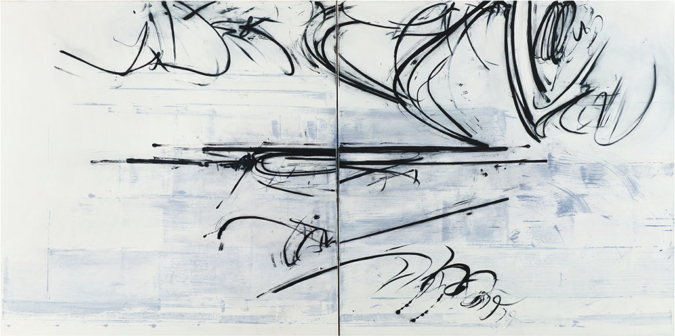

A studio visit is a rummaging affair. One digs with the artist through the past while being surrounded by the present. Time loops prevail. The loops wind back and forth through long-standing concerns and bump into present preoccupations. Naming Game (2001-2003) itself is a body of Moser’s paintings from the early 2000s. Diptychs, nine pairs in all. Some are as large as 5 x 10 feet, “stage like paintings” the artist has called them. Some come in at homier sizes, as small as 12 x 24 inches. Moser, perhaps as a mourning gesture —having just stopped teaching at Princeton where many of her closest colleagues were writers— reached out to a range of writers to collaborate with her on the project. There were critics like Lilly Wei and Nancy Princenthal. And there were other artists like Catherine Lee and David Humphrey. The result for Moser was to be the paintings, while the starting point was for each collaborator to line Moser up with pairs of words, thus generating a babble of voices to be heard or, indeed, seen by the artist while alone in the studio. Rules were wide open. Some participants came up with systems to find words, counting 20 words down in randomly selected pages from Nabokov’s Speak Memory. Some were found in punning and playful associations. The range is wide; there are conflicting words, alliterative words, unreal words, fighting words. The words shimmer or detour through different modes of telling, meaning and signing. They are like street signage but they are also the spoken word. The choosing seems to have high tailed in sometimes balanced and sometimes bumpy directions. Moser knew the writers. One imagines her hearing their voices, discerning their accents. For the artist one can only imagine to what extent, and how quickly, the words become graphic icons while remaining as aural impressions.

In this way Moser was delivered of a deliberately goading and teasing vocabulary. Her interlocutory tack was to roll with the connotative punches, playing off the words. Sometimes this would be a visual or iconographic play. Sometimes affect laden associations bounce into ones mind. In Bloom Shadow, 2003, subdued grey forms mimic the more prominent rust colored shapes of the foreground; a back and forth agonistic tryst plays out about who has the form and who is the shadow. In Stone Split, 2002, the pile of ovular spaces marked out by scribed lines adumbrates a mini henge. With Full Before, 2002, the boundary line demarking the two panels of paper strikes through the disks rendered, linearly, across that boundary. A maudlin tensile sigh is almost audible. One panel yanks disk from disk violently rending the ovular harmonics. While in First hand, 2003, large at 68 x 136, there is a tilt toward the chaotic and the frenetic, the loud, loud action of a pinball machine rattling close to “game over” cannot be far away.

This body of work is not exactly call and response, not exactly communication by return post. But, for Moser, the relationship between panels of a diptych –or from mark to mark within a painting– is key throughout her work. It is like the articulation of language, the immanent is put to work and a relation emerges between elements. And in that relation a space for working out something like an affective payload emerges.

It comes as little surprise then that in conversation Moser will remark that not infrequently her work has been based on “language models.” And pretty much in the same breath she will invoke Roland Barthes. Barthes enters the conversation both in general, as mandarin figure per semiotics but also quite specifically in terms of his volume A Lover’s Discourse. In A Lover’s Discourse Barthes uses a particular, to my knowledge unique, form of citation. He abandons the formal established practices of notation or footnoting while invoking the haunting, and inevitable (his point I think), presence of other authors, other voices in his own text. In the margins of his pages, for A Lover’s Discourse, dangle single words, names, Werther, Winnicot, Heinne. These are not formal citations of a quote or even a readily available influence in the adjacent text. They are better thought of as spectral presences, or emotional satellites drifting in the writer’s mind, which accrete to the given text. For Moser, like Barthes as a writer, this is what it is to be a painter, awash in ghosts. In Naming Game she conjured up the ghosts via a simple invocation of friend’s voices. But the haunting stands as enduring fact with or without such invitation.

The puzzle that Moser chooses to tussle with is how a brush gestured across a surface can be detoured to produce signs that an other will extract meaning or affect from. Put another way the question would be, how can she control, or better, shape the relationship between so many voices. Of huge importance for Moser, was the fact that although much of the theory of semiotics mulled over in the 1970s came packaged with Continental Philosophy a seat was nonetheless reserved at the table for C.S. Peirce. Reading Peirce ushered in a more nuanced notion of semiotics that allowed for, what would become crucial to Moser, the indexical sign.

One of Moser’s early heroes, Stan Brakhage, may have led the way. True, he perhaps cheated somewhat, in that he did not trail a brush, or a pen, or in his case a camera lens across anything. In his first cameraless film Mothlight (1963) Brakhage takes two strips of clear leader stock. Between these strips he sandwiches, variously, wings from dead moths but also flower petals, blades of grass and small scraps of other flora. Upon projection a frameless stream of seeming abstraction –but, importantly, not actual abstraction– slides before the viewer.

One is struck that there should be naught to tell only moths to show. The film should be a species of poetryless ‘realism’, a clatter of Indexical signs. Yet, because the actual referent is used to make the sign, and because the work pays no mind to the demands of film frame-size or any technical demands of the mediating system of camera and projector one cannot help but feel that the whole project of semiotics is somehow bamboozled by Brakhage’s esoteric practice. What should be “The footprint in the sand, the sign about which Robinson Crusoe makes no mistake” is instead a confounding territory of ghoulish slippage and hallucinatory blurs. On top of it all the now abstract footprints in the sand give way to a subversive poetic terror at the thought of the moths drawn to the light of Brakhage’s projector and consumed therein. In Brakhage’s hands the indexical sign turns deeply enigmatic.

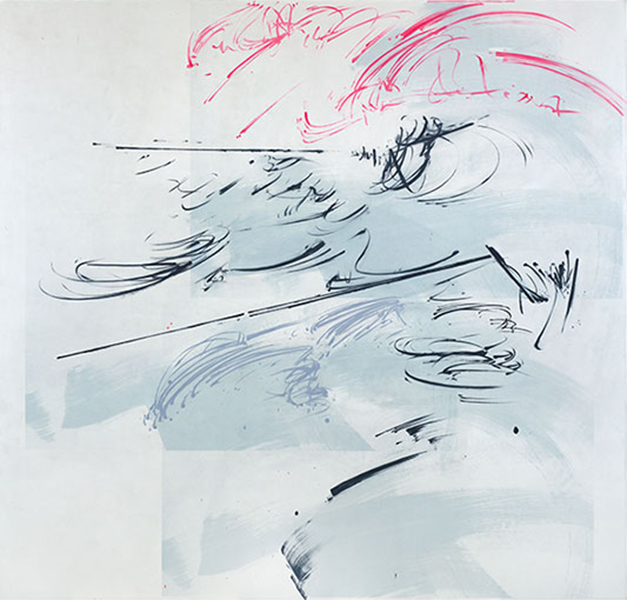

The point here, relatedly, is that Moser is taken, very much taken, by the idea that as a painter “you are documenting something as you are expressing it,” you are “recording as you are describing.”As in Ink & Murmur (2016) the gesture of Moser’s wrist or arm movement is traced upon the canvas surface. Which is to say that the mark on the canvas is the trace or index of the artist’s physical gesture.

Moser is showing us, ever so quietly, that this is an indexical sign of the artist’s hand, but she is also pausing in awe (or dread) at its complex openness. There is a nod to Brakhage here for sure. But it is also a nod to the enigma at the heart of Moser’s self-described process.

“Improvisation plays an important role in my work, but my decisions are not random. As a painting or drawing develops it gradually reveals its own logic and stance. It suggests certain possibilities that I then work with. But it is really through the teasing of form and gesture, each insisting on the other, that the image emerges.”

And so it is that the painter’s body and the signs it makes work together: Moser’s own words, “. . . teasing of form and gesture each insisting on the other.” There are multiple layers of dialogue at play, routing backward and forward in time and history. Jean Laplanche has argued that all communication, all utterances, all signs drift not just across or through the enigmatic medium of language but they also loop through psychic time and idiosyncratic history. Signs sent to others, to oneself, are never clear and precise. For Laplanche it is this enigmatic traffic, not repression, that situates and forms the unconscious. In Moser’s studio practice the relationship between the mark, the historical frame, the title and the painter’s body preserve, as Laplanche has put it, “the sharp goad of the enigma.” The marks on the canvas’ surface are leased out to Moser by herself for her own enigmatic soliloquy, come monologue, come dialogue.

Indeed it as if Moser were resolving, retroactively, the enigmas posed by Brakhage et. al. as they disassembled cinema’s clear narrative lines. She is deposing (in all senses of the word) puzzles lodged in her unconscious since sitting in the darkened rows at Anthology Film Archives.

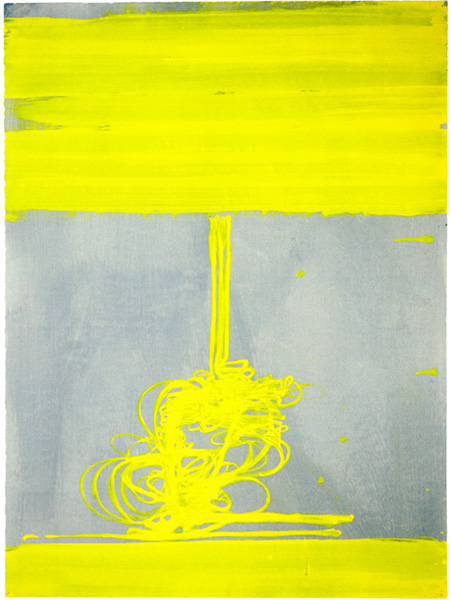

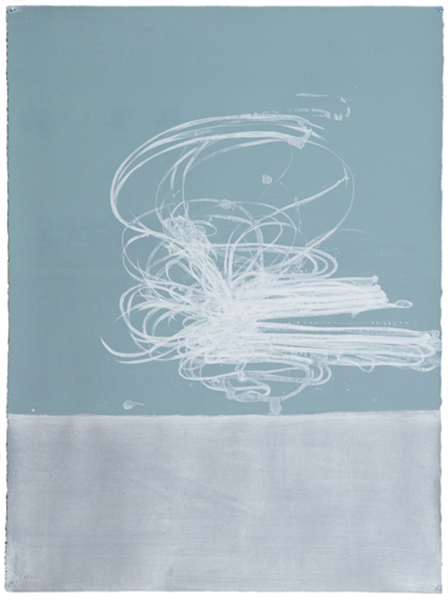

Stills

In Stills a series of 20 paintings from 2006 Moser pushes her cinematic unconscious to the fore both by dint of the collective title but also by the montage like presentation as a sequence where the viewer tracks back and forth from panel to panel (or frame to frame, could we say) grasping at the jump-cut like spectral space between each rectangle. Though, for Moser, the actual cinematic organization of frames in sequence on rolls of celluloid is not the necessary or exclusive reference point. Moser has long been a fan of George Herriman’s Krazy Kat with its often disorderly narrative journey for the reader around the page from frame-to-frame, panel-to-panel. Indeed in Stills if you squint, you can imagine Moser paying homage to Herriman’s graphic chops, his frame filling graphic strides and his talent for showing a brick in motion and coming to a halt at Krazy’s head. As if Moser’s marks were, here, loaners from Herriman’s post-apocalyptic landscape, (noodling as it surely does through the synapses of Moser’s memory) while the fractured language of Herriman’s characters could be muse for Moser’s again and again toying with language’s routing and re-routing of meaning.

So an image or line appears and a lure is spun out with the sure knowledge that some other image, line or frame will follow. But in quite what relation we cannot predict. Brakhage led and teased with titles, Mothlight. In her way, so does Moser. “Stills” directs us, leads us down a path, but faithlessly so. We don’t quite get what we have been led to expect. There is a spooling out on the painted surfaces that is not retrieved by the titles. Instead there is a poetic sideways shift. And insistently the mark that signals its own making, signals the gesture of the body that made it. There is a continuous working through of mark and gesture. Her practice, at the point of contact, standing at the canvas, is a form of dialogue between instant and gesture. Her action resolves as a gesture stretched through the duration of the mark.

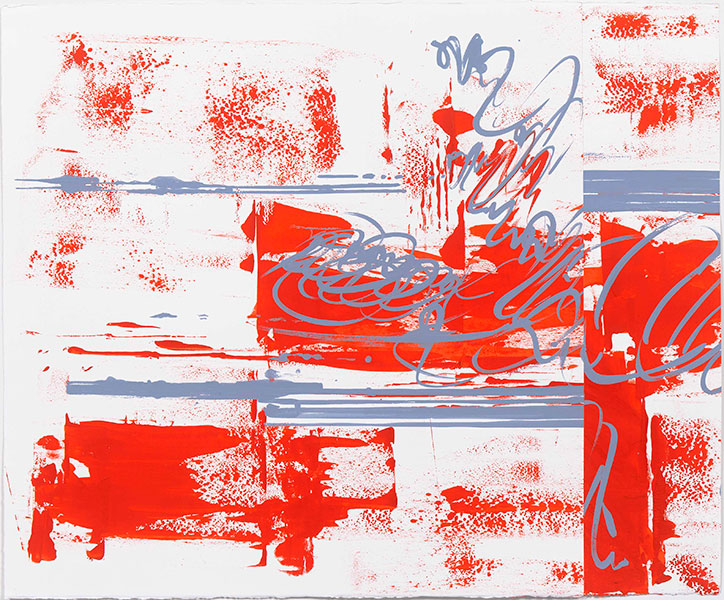

Play Replay

Moser’s most recent work, collectively shown under the title Play Replay (2017), also reprises cinema references. In its way it even takes us there through its the implication of its overall title: Play, Photoplay. . . . More specifically the individual titles of the pieces Vertigo, Screen Test, Tracking stand like Barthe’s margin notes in Lovers Discourse, as signposts toward a spectral presence. No clarifying explanation is given, but the marginalia clings to the main show imbuing it with history and copious reference.

In these paintings there is, arguably, less and less visual information offered. One is aware that one series of marks, possibly the foreground, signal the hand or wrist movements that made them, as in the already mentioned Ink & Murmur (2016), while the other presence on the canvases tends to be a stain or fog like background applied through a silk screen printing process. Body gestures are clear while vision is blurred. At times the foreground marks imply cursive script, even the signing of a name. At others it is Herriman’s borrowed marks —usually signaling some violence— all over again. In speaking of these paintings Moser explicitly identifies the mark as the trace of the physical, bodily gesture that made it. And she directly cites 1970s avant-garde cinema as precedent. Minus the moth wings we are dancing with Brakhage again. But Hitchcock and Godard are also quietly (maybe not so quietly?) with us. Her insistence on the clarity of the indexical is there, assuredly. Yet the emphatic unconscious presence, recycling back and forth in both psychic and studio time, is a cultural haunting of cinematic histories.

If we are to take Laplanche at his word it is in the enigmatic status of the messages bouncing back and forth through time, and still yet to be resolved, that our unconscious toils. Moser’s gestures along with her titles, along with her decades long fraternization with cinema return to those enigmatic signs to rework and re-mine them again and again. There is a refining process in this. As the meaning or narrative comes to be known or fixed she undoes that fixing. Just when we knew that dead moths were dead moths she turns them into the line that signals the passage of Ignats’ brick toward Krazy’s head.

In some quarters of psychoanalytic practice there is a notion of ‘returning the signifier.’ A word from the analysand’s utterance will be returned to him or her, shorn of context, by the analyst. Usually it is not a word that would seem to have much conscious or unconscious psychic freight. This gesture is a technique for derailing sterile narration, for opening up the analysand’s associations. It restores the enigmatic status of language.

This captures something of Moser’s process in the studio. Well worn, familiar, echoing voices and signs are returned by her to the canvas’ surface in dialogue with other passages and sequences of paint. She disrupts her own painting discourse, her own rich history by redescribing it as she records it.

Studio photographs of Jill Moser by Lauren Pascarella

www.jillmoser.net

Insightful essay and loved seeing how the work has evolved!

Jill, this is such a wonderful walk through your thoughts and paintings, an insight into painting that keeps the medium, and your studio, fresh and continuous.

Romanov, your in-depth revelation of Jill’s artistic process gives this analysand hope.

Love every stroke and interplay

Wonderful language