Dahlia Elsayed: Words to make maps by

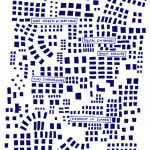

A day in the studio begins for Dahlia Elsayed with the un-redundant technology of carbon paper. Sitting at a small ribbonless 1970’s typewriter Elsayed will free-write whatever comes to mind. The mechanics of the operation are that invisible sentences (remember, “ribbonless”) wind out across the blank page as Elsayed selectively depresses the keypads and, responsively, the typebars slam the paper. Elsayed remains blind to her effort until she removes the page from the machine and then reveals to herself the carbon-copied version from behind the blank page. The whole scene is redolent of a character in Beckett at struggle with the spooling nature of a language that needs to be corralled and parsed.

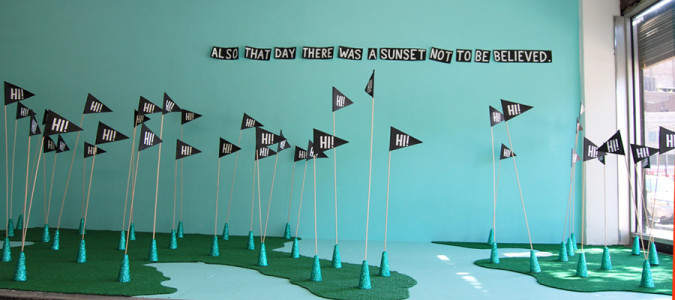

Elsayed trained in a hybrid creative writing and painting program at Columbia. She was a poet with a painter’s studio trafficking in dislocated words and images from maps, road signs and nautical flags. Unsurprisingly language remains central to Elsayed’s visual project and words, as written, painted or drawn by her, are enthusiastically visual things. At times the words feel like a phrase from the middle of a sentence, lost or orphaned. At others the feel is of a hail to the viewer in a frank mode of direct address; “Hi!” as on thirty spindly flags arranged across the gallery floor. Throughout her project claims are made, renounced and then re-announced for a dual provenance in painting and poetry. This claim directs her dialogue between the quotidian poetry of found words and the rallying of the same within organized texts. At times Elsayed is the anti-grammarian. Parts of speech are sundered from one another. A phrase that should connect, say, subject to verb, pauses in expectant space. Or an independent clause from a complex sentence is granted way too much independence and hovers apprehensively awaiting a subordinate clause.

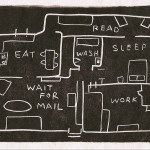

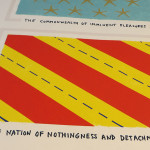

Consistent with this attention to language one finds that throughout the work there is a deliberate tactic of treating the labels, directional signs and devices borrowed from cartography as concrete entities. It is a ploy that foreshadows a calculated confusion between sign and referent, a sort of anti-semiotics where such devices colonize sculpture or painting as literal things in themselves. One sculpture, for example, executed while traveling through the southern states of the USA is a long dotted line on the ground –sharpie on paper– marking where “The South” begins. Inscribed in the actual landscape the cartographic convention trembles with mythic, historical and cultural freight.

And so, sense of place being important to Elsayed, it is no accident that flags, that most conventional claimant of place or territory, recur in the work. Winter of 2008, atop Independence Pass in the Rocky Mountains, the artist installed a series of flags made from tissue paper. Titled, Till The Consummation of All Things, the sculpture tried to hold its ground in an arid, tundra depression at 11,000 feet. Something of the mystique of mountains and their summits is evoked in all this, the place where one finds ones guru, or where god dispenses tablets of wisdom. But yet, gods and gurus aside, at 11,000 feet in the winter, the wind is easily strong enough to disintegrate tissue paper. Thus, Valhalla’s flag made its relatively brief claim upon Colorado’s geography, and so too did flags offering “Heroic Thrusts”, “Magnetic Pull” or “Some Great Thing.” In such manner the psychological and topographical meet in flag borne phrases, visually echoing across mountain valleys as the paper disintegrates and scatters. Elsayed cites William Carlos William’s epic poem Paterson as a reference for her practice in general. She shares with him a talent for using a musical language to scatter emotional hollows across space. For Williams that space was the page where he offered poetic reportage of a ravaged New Jersey city. For Elsayed here it is Independence Pass with that name itself resounding within her poetry come sculpture.

Flags again, but with a very different sense of place. In 2012 Elsayed installed a project at The Newark Museum. Thirty or so yellow nylon flags lined the intersection of Central Avenue and Washington Drive where the museum stands. The text upon the flags was a “reworking” of lines from John Cotton Dana’s essay The Gloom of The Museum. Dana, a Progressive Era cultural populist who founded The Newark Museum, demanded democratic access to cultural production and consumption. He included contemporary American commercial products in the museum as folk art. (Most famously he ushered plumbing into an art venue two years ahead of Duchamp when, in a show titled “Clay Products of New Jersey”, he displayed two porcelain toilets from the Trenton Potteries.) If in Till The Consummation of All Things Elsayed’s flags heroically waved messages to the truckers and tourists braving Independence Pass in winter, here in Newark a “flag poem” as Elsayed has called it, hails, exhorts or converses with Newarkers in phrases and paraphrase from Dana asking that we “study our tea cups”, or “show ourselves plainly”. The Danaesque move that Elsayed makes, the one that all but trumps Dana, is to actually step outside of the museum into the democratic space of Central Avenue. While this work is not precisely interactive, while it is not exactly social practice, it does nonetheless prey upon the organization and context of cultural space, social encounter and spectatorship. Elsayed’s flags loiter at a distance from the museum fraternizing with the public at large. In this way spectatorship becomes something like an enforced democratic task rather than a chosen option. Importantly this is not a form of spectatorship invented by Elsayed. She is simply, and quietly, appropriating the mode of address of advertising, or urban signage in general. The difference being, that Elsayed’s flags do not participate in the normal functions of such signage; the artist is not selling us stuff. Rather she is depositing terse, koan-like pronouncements into the cluttered and all but accidental discourse of public space.

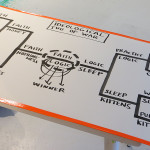

Not all of Elsayed’s work is flag borne. In 2013, while on a visiting artist residency at Austin Peay State University in Tennessee, Elsayed organized a much more direct foray into performance come social practice with an Ideological Tug of War . In the end the whole event was also a way to get to a poem but en route dozens of people participated in competitive struggles between pairings or dyads of opposites authored by the Austin Peay students. Thus money combatted passion, work was pitted against sleep, puppies against kittens and so on. In a knockout tournament the categories, anthropomorphized by teams of students competing in a tug of war, vied with each other across a muddy campus field. The final poem –there are many minor poems along the way in the form of T shirts and such– is the annotations of the performance come competition. This poem takes the form of the scorecard of the knockout eliminations and as such is a sort of automatic writing largely out of the control of the artist. If kittens had pulled theory across the line in the mud, instead of losing out to sleep as they did, the poem would have been entirely different. Here, then, the artist is skulking around words that are quite intentionally not hers. She is all but stalking random words in order to pin them down as an image. Nothing as obscure or arcane as a caligram is sought, Elsayed is out for quotidian word-scraps, the left-overs.

When not from her free-writing or journals (more on them below) the point of origin for Elsayed’s text will often be incidental, thus she embraces vernacular sources. There are the already noted road signs, but also she plunders menus, weather reports or sports announcements. Frequently, in her paintings, sculpture or installations, the tension, both visual and textual, is anchored by the sense that there is no internal agreement between the elements: in fact, no anchor. The words have rushed in from the middle of nowhere to be affirmatively present. Affective resonance chimes through this presence. There is a shifting in emotional registers as the words appropriate their newly given context. The words jostle for our and each other’s attention. Just think of Independence Pass with all those flags waving to each other as well as to the truckers; geography is remade into anecdoted topography as Daniel Spoerri et al might have put it. And the words just keep on creeping up on you, they keep on inhabiting physical and mental space as if poetry just spontaneously happened.

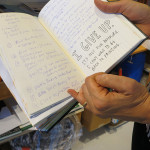

As much as place resounds in Elsayed’s work so too does history. Home from Colorado mountains or Tennessee, in her studio, located in the house where Elsayed grew up in New Jersey, the studio walls are lined with the artist’s own archive in the form of journals. Journal writing (and drawing and doodling) being an activity that Elsayed traces back to her teenage years when “punk slogans” were the poems de jour. Where that teen archive morphs into the artist’s one is not precise (and probably not important). However the back catalogue weighing the studio shelves down, folds the entire activity into a private, affective yard stick of the world that is gradually, over the years, accessed as a piece of the artist’s public voice. One could think of it as a circular migration from journal to studio and back again, wherein partial annexations of the journal-writer by the studio-artist body forth in paintings, poems or sculptures.

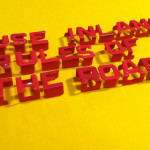

Sharing shelf space with these journals, salvaged from a restaurant on the aforementioned trip to Colorado, Elsayed has stashed many boxes of plastic letters. They are the stuff of very functional reader-board announcements. The doodads that could be used to tell us what is for today’s lunch at day camp, say, or, which room for eye tests at the DMV. For Elsayed they are not exactly non-functional, nor are they envied for their redemptive poetic power. They are, though, grist awaiting deployment in future poems, come texts, come sculptures. In the end it is not that Elsayed takes the notion of “functional communication” too seriously or not seriously enough. It is more that she deliberately courts something like the rustle of aphasia as a way of testing the limits of language’s musical range.

Congratulations Dahlia!

Very enlightening!

Love your work.

All the best.