Curtis Mitchell

It is said that Warhol once said, “I just happen to like ordinary things.” This is not something one imagines Curtis Mitchell saying. When Mitchell has his way with ordinary things, objects purchased in the day-to-day transactions of consumer culture, he is using them to forcibly recant the adamantine grip of kitsch upon American society. Often times, in their encounter with Mitchell, these “ordinary things”, the purchased objects, will become broken, soiled or ultimately vandalized. Plumbing fixtures, furniture, rugs, sometimes fine art objects find their way into his studio, and thence become damaged in some manner. Sometimes it seems that Mitchell has tried to repair, modify or improve the object. A men’s club wing chair is repaired with a disorganized rainbow of duct-tape; an “oil painting”, which could be a copy of a Malevich cross, (in fact it ‘could’ be an original) is similarly held back together by an insane medley of tape while an aquarium, minus its tropical fish, is glued back together with one is not sure what.

In one suite of work anonymous snapshots are enlarged to giant (for a snapshot) proportions, whereafter they are, to use Mitchell’s word, “ruined”. They then appear to the viewer as abstractions of chemical stains. Ghosts, not completely destroyed by Mitchell, peer at us from deep within the surface. The images slide in and out of, not so much focus, but more between poles of abstraction, representation and death. Or, on point, an Elvis un-sighting will show a poster of the mid-American demigod torched and massaged with, “Equal amounts: Dirt, Makeup, Toiletries, Varnish . . . eye shadow, toothpaste, glue, shaving cream, soap, moisturizer, lanolin, hand cleaner.” Elvis is sanitized, glamorized and deleted in a single movement. With a related sequence, Meltdown, every household chemical under the kitchen sink is applied to, “photographs of light, completely black monochromes,” recasting the monochromes as frenzied, unwound skeins of lurid color. In all this Mitchell is harnessing both a romantic attachment to the ruin and a regression to the practices–better put, poetics–of the juvenile delinquent. It is thus Mitchell’s method to create his own ruins (and in his words “improvements”) all the while being mindful that the ruin he has at hand is contemporary America.

At two stories in height Mitchell’s studio architecture begets theatrical metaphors, it allows for site lines and balcony views. Currently in the studio there is a pack (or packs) of dogs. They are the skins, pelts, of plush toys stretched across slender frames. The pelts sag. The pack appears hungry. Viewed from on high –a parapet running along three sides of the studio allows for an ‘as the gods’ perspective into the twenty foot high, or deep, space with a brick like stone floor– the pack prowls across the space. Black fur set off against red brick floor sharpens the visual relief. The pack is closing in on something? Projected across the pack at a lowish level Mitchell runs Rachael, a video loop of a love scene between Rick Deckard and Rachael from Blade Runner. Thus layering the pack within the visual field of the projection while simultaneously ghosting the faux dog’s shadows upon the dystopian space and time of Los Angeles 2019.

This is a video device Mitchell has worked with many times. The discrete spaces of projection and viewing are collapsed. Fourth wall safety is abolished. The viewer, turning back in the cave like space, is blinded by the projector. Platonic shadow scenes play out in one obedient direction, while rebellious unchained viewers’ turn back to find themselves among the pack of dogs.

It is always a mournful terrain, that of the artist in relation to animals. Beuys trod it incautiously with his dead hare and more so with his less than wily coyote. Douglas Gordon’s elephant, playing dead, is invoked by Mitchell in tones of a ritual pilgrimage: he took his son three times to visit the Gagosian installation. While Bruce Nauman’s animal pyramids, surely, stalk the background of any contemporary artist’s unconscious. Mitchell’s lament is of course at a remove. It is the kitsch stand in for the animal, the stuffed toy, that he anti-taxidermies. His is a winner-takes-nothing emptying of the plush, tender comforting feel of such toys. A back to zero potlatch where you are left on your own with the synthetic pelt, your unmet emotional needs and the packs’ apparent hunger. Meanwhile, off to the side, away from the pack of dogs, in an ante room, Mitchell shows us a white rabbit stuffed with, or more accurately tortuously stretched over a giant log. Horrific, sadistic and funny it could, indeed, be a cousin of Wile E. Coyote hoisted on his own Acme petard.

Then on another site line one catches a glimpse of the tiger. It is a work in progress where Mitchell is, as yet unsure of the terminus, unsure where it will end. The tiger waits sequestered, lingering in its corner. Lank fur come derma, like the dogs’, is draped across a frame that deliberately does not flesh it out. Hungry? For sure. As a piece of work the tiger will resolve –or not– but in the moment its stationary pose standing in the corner, like a punished child, seems to mark out the varied emotional territories of the studio in the daily practice of its occupant.

Video of Jennie Nichols and Bonnie Rychlack interviewing the artist in his studio. Camera by Tania Cypriano

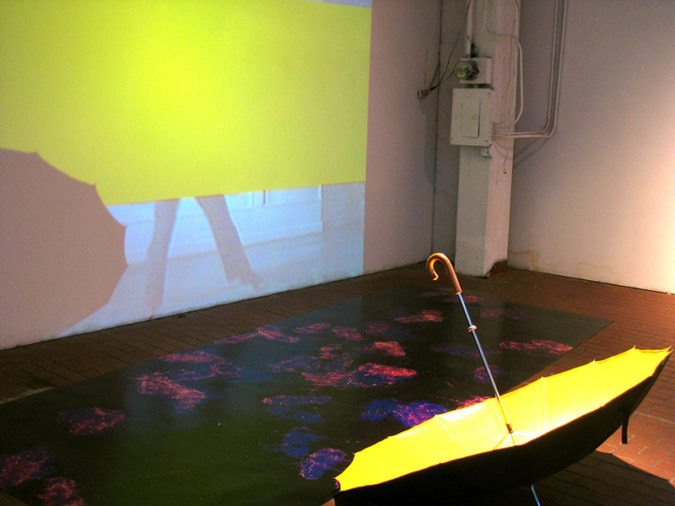

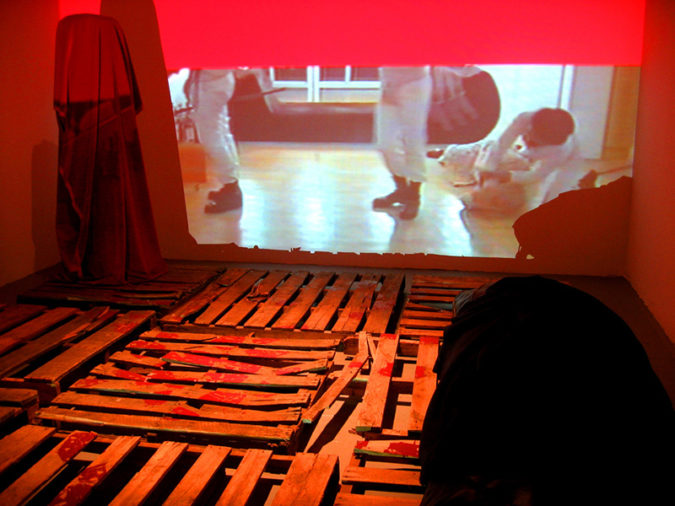

Long ago Clement Greenberg warned that kitsch offers “a short cut to the pleasures of art.” Implicitly we seducible viewers are oblivious to the wiles of kitsch, swept up as we are in its easy pleasures. The classical cinema of Hollywood is an obvious touchstone for this and in his video installations Mitchell thus takes the necessarily long route around such cinema. In an ongoing series of video installations, generically tiled Personas, Mitchell simultaneously literalizes and unmasks the processes of identification and suture in classical cinema. The pleasures of psychologically throwing oneself into the fiction and participating in the constitutive moment of ones own moribund Hollywood subjectivity is explicitly played out in the installations. Looping short and, variously, famous or notorious scenes from Clockwork Orange, Reservoir Dogs or Singing in the Rain the video is projected in the exhibition space—similar to the current projection in the studio across the pack of dogs—in such a manner that the spectator’s shadow plays across the scene, obscuring the image but also literally incorporating the viewer into the filmic moment. Meanwhile the face of the performer on the screen is barred from view by a broad digitized stroke of color. On the floor large format C prints representing the dance steps of the actor—McDowell, Madsen or Kelly—invite the viewer to ghost the performer’s movements.

Mitchell has said he wants to remove the anxiety from his experience of the kitsch. But he is also disciplining kitsch, refusing to be bullied by it easy satisfaction. To kitsch’s easy promises Mitchell counters with obstacle and delay. In the Personas series there are literal obstacles, ‘props’ extruded by the projected image it seems. An umbrella, shipping palettes and such litter the space. One’s own shadow, incorporated yes, is also one of these obstacles. Also the pieces are silent: audio off. One is left silently sort of viewing the film clip while sourcing the sound track from memory. One’s own interior ‘space’ is annexed and true absorption and narrative pleasure is adjourned. Mitchell relies upon the familiarity of the films he uses to defamiliarize them.

Frequently Mitchell will return to objects, strategies or devices he has already used. As he puts it, “I just figure no series is finished. I’ll always keep going back to this stuff.” Rugs, and floor pieces that allude to rugs are a case in point. In the past rugs were burned, then painted then sent to the dry cleaners. The conundrum of floor and wall, whereon does the rug belong, is implicit but it soon fades from ones attention and the rugs take on the personality of paintings or tapestries. In the earlier pieces Mitchell seemed to be navigating between the romantic drowning pool of a Rothko and a jazz riff on petite bourgeois taste for ‘oriental’ rugs. Recent rugs, hanging currently in the studio, are being addressed differently; Mitchell is unraveling and unweaving them. Again the sense of the artist-made ruin is there. But the accent is different. These rugs are being un-made, not simply destroyed. This is cultural production in reverse. Banal or neutral as home furnishings, they are the sort of rug one buys in Target or T.J. Max; not ‘oriental’ investment rugs. The un-weaving redeems these rugs. They are more interesting now. Mitchell adds layers of texture, mystery even history. He adds the history of ownership and marks the object with traces of desire, or need. His anxious, tic-like, whittling of the weave and aggressive tugging at the weft mark the piece with affective freight. These are now narrative rugs, the Bayeux tapestry sans iconography. They are the story of the artist defending his studio from the invasion of kitsch.

So what is one to do with all those ordinary things that Warhol liked so much? Mitchell has long ago adopted a scorched earth policy. There is his dark trope, tirelessly at work, of undoing the life-world of the lower middle class. But while the emotional register of kitsch is argued to be shallow, narrow or limited; this undoing of the object brings an emotional depth to both the object and to the artist’s project. The damage done by the artist evokes a certain anxiety. One feels protective; of what or whom is unclear. There is a sense of vulnerability; for what or whom it is uncertain. In that kitsch fails to engage the shifting complexity of human needs it can only offer ersatz indulgences to gratuitously manufactured desires. Kitsch has no redemptive power. Think of all those plush toy rabbits Mitchell has used up over the years. And recall that the Hare, once a Christian symbol of renewal and resurrection (cf. Beuys), ends up each spring as a glut of chocolate Easter Bunny Wabbits. It is a form of symbolic ruin and destruction that we all love because, well, chocolate really does satisfy desires. Mitchell is, then, basking in, or searching for, the gloaming of petite bourgeois taste. However, he knows that petite bourgeois taste is resilient; even so, Mitchell is determined.

More of Mitchell’s work can be seen at http://www.curtismitchellart.com.

This is a wonderful overview and long overdue!! Bravo!

More evidence of your wicked subversive head. love it

Outstanding commentary Curt. Very intuitive. Hope you are well, my friend.