Arthur Simms

Citizen Simms: Unpacking Arthur Simms’ Studio

As Citizen Kane draws to a close –I am thinking of the penultimate scene, the scene before the “Rosebud scene”– the camera pulls back to allow the frame to become filled with the fillings of the vast storage at Kane’s Xanadu. Kane’s scavenging come hoarding slowly fills the frame –fills all the space there is– squeezing out the presence of art and history, squeezing out the tiny little actors at the bottom of the frame. Abundance, it seems, squeezes out the particular. For those trapped within the diegetic space of the film the “Rosebud” enigma will remain unsolved, unseen as the credits roll (And thereon for an eternity of re-screenings). But for the attentive spectator much will soon be explained.

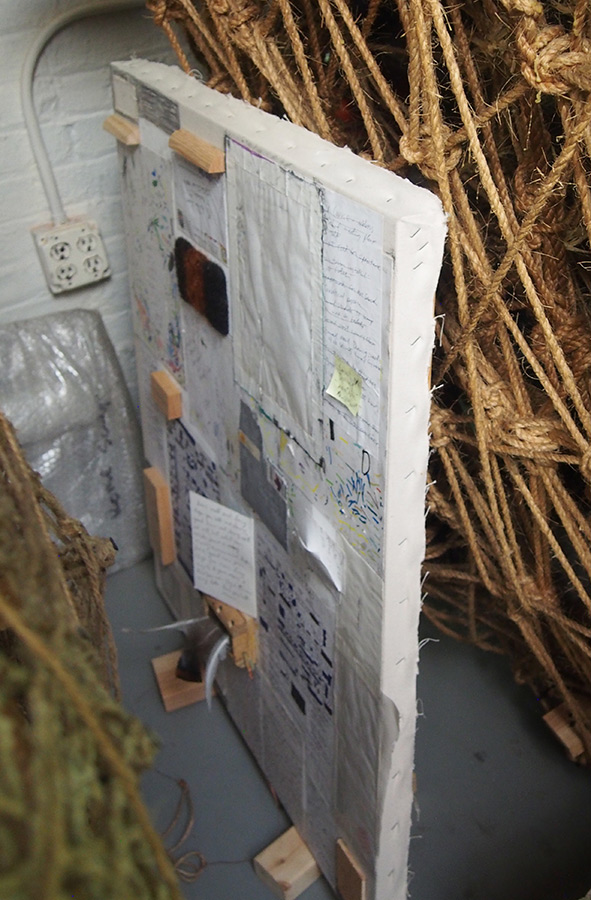

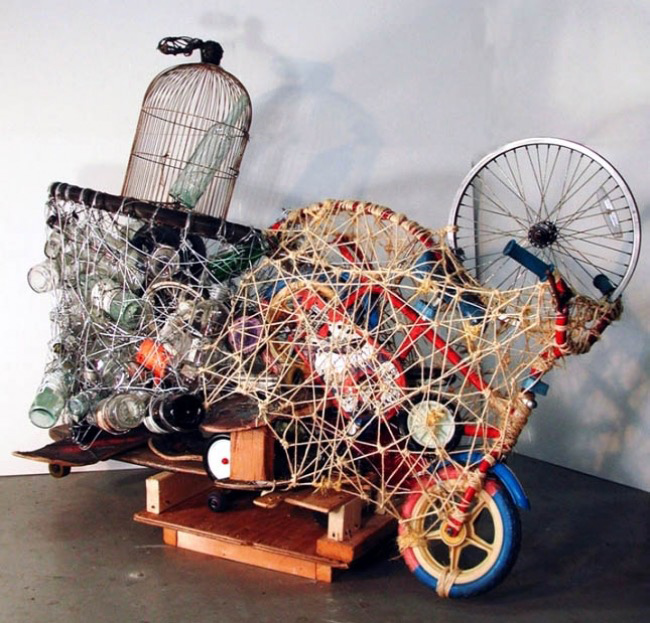

In a way, if you squint, (or if you crave cinematic similes) the opening ‘shot’ one gets on entering Arthur Simms’ studio bookends that penultimate shot in Citizen Kane. Round the first corner in the studio and close to forty years of Simms’ work crowds toward the visitor. In “Kane” the plundered antiquities and art are boxed, crated, unseen, unknowable. And we as viewers are retreating from them along with the craning camera. With Simms we are moving in toward them. Moving in for the close up, engulfing ourselves with each step we take. In Simms’ studio there is a dearth of crates but there has nonetheless been much swathing and wrapping. For Simms the wrapping of objects is both an essential technique and a prevailing figurative device. It has evolved, over many years and many sculptures, to be a mainstay of his studio practice. For Simms wrapping is part of what transitions objects into sculpture. Thus he wraps these objects, sometimes tenderly, sometimes brusquely, with wire, or with rope, or string, or sheets of glassine, scraps of lumber, stretches of aluminum foil or newspaper.

In the studio

At Xanadu someone has presumably catalogued and recorded what is in all those crates. Or they could be empty; they are just props. Still and all the spectators will never know. And it is not very important anyway. The kitsch revelation in the final scene will do the emotional heavy lifting. Contrarily, in Simms’ studio it feels clear that this is wrapping and not, say, just the surface or patina of his sculpture. And it is very, very certain that this all has nothing to do with the pragmatics of crating to ship or store. It feels clear that there is an inside to the sculpture. Some thing has been wrapped. But more than that, the action and presence of the artist is embalmed within the wrapping of the object. In this sculpture there is an object but there is also the history of an act. There is a yesterday, and an unconscious. In this way the work is loud with an occulted presence.

Simms’ first began wrapping sculpture around the late 1980s. Left Foot (1989–1990) is the first he recalls. That there is no extant image of this piece illustrates one of those tales that chart the long haul of many artists’ lives. Simms had to vacate his studio of the time. The sculpture, too bulky and cumbersome to move with him, was defenestrated by, well, as he puts it . . .

“I paid a couple of strong young men who lived upstairs from me to help me take the window frame out and then we pushed it (the sculpture) out the window into the back yard.”

Voila the work occulted into the gloomy history of New York artists’ struggles with real estate. The literarily, and evocatively titled, Crossroads, St. Andrew, Kingston, Jamaica, 1961–69, (1992) is the work that Simms identifies as “based on the Left Foot sculpture” Standing ten feet high and five feet wide it is only half the width of the original. (Try to imagine the original exiting that window.) Between the capacious scale and the evocative literary title there is much territory there for an artist to hide a great deal.

Simms confidently points toward Jackie Windsor’s Bound Square from 1972 as an important landmark in terms of wrapping objects. But, like many artists who have been in the studio for the long haul, Simms is dialoging with multiple strands of art history and these pop up hither and thither as one walks the studio. Jackie Windsor’s particular post-minimalist trajectory, with its self-aware knowledge of recent art history, which it both mines and pushes back against, seems important. As do her eschewing of the hardness and industrial metaphors of minimalism and her embrace of process. Likewise the mark of the hand and the history of the actions carried out by the artist are all crucial in Simms’ work.

Yet the history of wrapping is not just Windsor. Wrapping is the decisive overdetermined device of Simms’ daily practice. In speaking of the wrapping Simms invokes, alongside Windsor, Minkisi figural objects or sculptures originally found in cultures along the Congo Basin. More oblique than Windsor’s wrapped corners the contents of the Minkisi are not merely enigmatic, or concealed they are also powerful materials or spiritually charged substances. So if Windsor is wrapping something, putting it out of sight (a certain version of masculinity perhaps?) Minkisi are wrapping materials and objects that offer a cadence of occult power. For Simms, an intellectual and cultural see-sawing back and forth allows him to coax a studio dialogue out of post minimalist sculpture and traditional Kongolese artifacts. On top of all this there are also abundant references to cultures of native America and an ongoing scrutiny of certain Italian Renaissance figures and traditions.

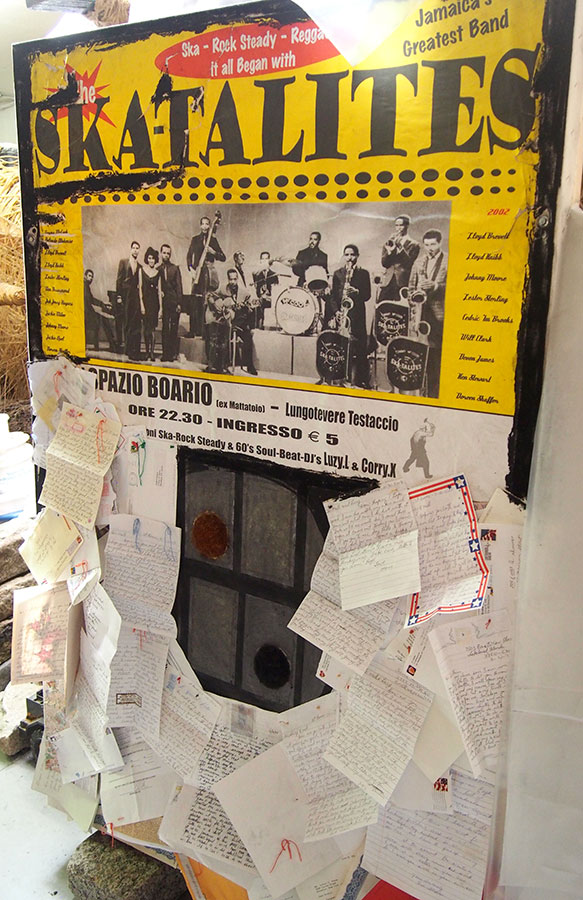

Diaspora

However, around about here, in the studio conversation, Simms does invoke the importance of diasporic African culture. His own Jamaican birth, ancestry and emigration to the United States are all a piece of this. (As is the vigorous presence of a large Skatalites poster in one sculpture —more later.) And in the studio there are sculptures that excavate the imagery of African-American traditions, bottle sculptures being one example. These evoke cultural wisdom and habit but also work formally to bring subdued local color to a frequently monochrome body of work. Such formal tribulations and historical, thematic concerns interpolate throughout the work.

In as much as any diasporic community is founded in the experience of loss, thus grief, there is a thread of the mourning ritual in the experience of Simms’ sculpture. Etymologically the word diaspora roots itself in dispersal and scattering. Collectively remembering –perhaps even lone remembering– proposes a reparative narrative which is, in turn, a means of binding together the scattered. But the diasporic narrative is also a shroud. It stands in for the missing, the lost home itself. It stands for something usually not attainable, perhaps not even known or imageable. Or something that is, for reasons various, difficult to talk about.

Wrapping in Simms is, perhaps, kin to the use of the blur in some post-war history painting. Richter is the obvious touchstone here, the blur as hazy memory, uncertain history, obscured or hidden history. Because Simms’ wrapped objects peek out, bulge revealingly or are visible from canted points of view there is a lack of clarity —vision is hazy and blurred. There is, then, something about the provisional and the contingent knowledge put before us by Simms in the act of wrapping and the enigma it enshrouds that hits the right note. Simms shies away from certainty as both a studio process and perhaps as a political necessity. We are never quite sure what or why the hidden is so. A scramble of affect accompanies the act of hiding. Shame, guile, aggression, retribution and much more are all there. The narrative –if that is the right word– of loss, dispersal and mourning is never complete and encircled. Loose ends, like frayed lengths of rope and string, abound in the studio.

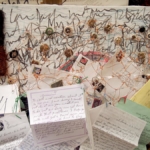

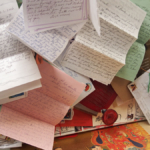

By way of example, there is a synecdochic parable of loss that Simms articulates across a series of recent works. The work is composed of ten pieces that Simms has completed as, in part, a mourning dirge to his deceased mother who was born 10/10/1924. The tens all resound with one another as if to invoke the rhythmic occultism of numerology. The pieces themselves feel votive. Very little is fully hidden. It is a public display. Simms shows us the letters written to him from his mother, the old I.D. cards of his and hers, that Skatalites poster. He includes patches of his own hair to affect an autobiographical brew. And while the arrangement of these objects creates —akin to theatrical blocking— site lines and blind spots, it is nonetheless the case that within the corpus of the artist’s work these ten pieces constitute a movement of revelation, even a secular annunciation. He makes himself, his personal grief, very visible. Makes his immigrant family’s connection across time and geography deeply important. And the travels, the movement of the artist’s mother from Jamaica to New York when Simms himself was merely 7 years old is, of course, a thread of the diasporic narrative. Personal history plays out as a representation of global history; the two wrap and re-wrap one another.

Formally Simms favors a textured surface. Lengths of twine or rope wrapped and spread into contours of texture by what they enclose. A fluffy, furry surface emerges that is not, in fact, entirely opaque. The impression could be of grisaille that paradoxically obscures. Thus, as already noted, in the sculpture you can sometimes make out what is hidden and sometimes not. In many cases part of the sculpture is not wrapped at all. In plain site a giant egg, beneath it a tightly wrapped form, a box, that may, or may not, hide something.

With Simms the act of making disappear, of hiding, is a horizon for the possibilities of knowing and telling. Secrecy is itself, a horizon for who gets to say —who gets to have a voice. In Citizen Kane if the viewer pays attention to the very end Welles tips his hand, reveals —‘Rosebud.’ Even for the boy wonder of Hollywood, the system of classical narrative pleasure demands this be so. Simms is painted into no such industrial-cultural corner. He tenaciously clings to the obscuring of knowledge, to the almost, but not quite said. In this way Simms controls the knowledge dial; who knows what and when. There is no spectacular entertainment to this, no abracadabra moment where the lady vanishes, as with Welles. Rather, the relationship of the viewer to the knowledge dial is pushed into the fore; we know we are not knowing everything. As viewers we are planted before the object, aware of enigma, of hiding and ambivalence, but also we are beguiled and seduced by the available surfaces and objects —eggs, knives, roller skates, toys— all of which shift and change with angle and point of view. For Welles there is no horizon, no enigma, Rita Hayworth is either in the box or not.*

So wrapping what?

In an early work Lucy Fradkin Meets John Delapa Or Gregor, 1992 Simms wrapped a painting of his own. It is not possible to see the painting. That is, one cannot gain a frontal view that would align picture plane and viewer. One can see the, by now, aged and somewhat battered corners of the painting as they poke out from beneath and behind the hemp rope wrapping. In this instance wrapping is a stand in for history lost or erased —but not entirely so. We do know that the Lucy Fradkin of the title is Simms’ long-term partner while John Delapa remains shrouded by the “or Gregor.” As for Gregor, that luminously solo given name in the title, Simms freely acknowledges the allusion many to most readers will assume (thus not very hidden), i.e., Kafka’s Gregor; that dyspeptic, decentered, transubstantiated subject of European modernism.

In an early work Lucy Fradkin Meets John Delapa Or Gregor, 1992 Simms wrapped a painting of his own. It is not possible to see the painting. That is, one cannot gain a frontal view that would align picture plane and viewer. One can see the, by now, aged and somewhat battered corners of the painting as they poke out from beneath and behind the hemp rope wrapping. In this instance wrapping is a stand in for history lost or erased —but not entirely so. We do know that the Lucy Fradkin of the title is Simms’ long-term partner while John Delapa remains shrouded by the “or Gregor.” As for Gregor, that luminously solo given name in the title, Simms freely acknowledges the allusion many to most readers will assume (thus not very hidden), i.e., Kafka’s Gregor; that dyspeptic, decentered, transubstantiated subject of European modernism.

How do we move form the memorably decentered subject of European modernism to the destroyed subjectivity and history of dispersed peoples? I have not been able to find any etymological connection between disappear and diaspora. But they surely sound like they have to be cousins. To disappear, disperse, go away, be gone. Surely? There are many reason why one might see less than clearly; reasons why one might hide something, not know something —like Gregor and his identity. We see unclearly perhaps because history is unendurable (or that, and too shameful; Richter’s dilemma), or perhaps because knowledge is painful, because identity has for too long been used to oppress one.

Dispersal is of course a movement, usually an involuntary movement. It is perhaps a movement that truncates cultural and social continuity such as that is. Plastically, in the studio, movement is a nagging and repeated presence for Simms. As Simms notes there is often-to-always implied movement in his sculpture. Many pieces incorporate found objects that originally moved. There are roller skates and skateboards. There are ice skates and bicycle wheels. There are homemade wheels and toy cars with wheels, dolly wheels and on and on. Often, usually-come-always, these wheels are close to the base of the sculpture. Close to, but importantly, not the base. Which means, of course, that they cannot function as wheels. The great lumpen sculptures cannot glide away. The wheels are part of the podium, which qua Brancusi, another touchstone for Simms, elbows its way into the picture to become part of the sculpture. Movement is, then, stalled by Simms’ placement of the wheels just above the floor and within the podium-come-sculpture itself.

Movement is itself a catalogue of possibilities. Is one on the run, escaping, chasing, hunting, emigrating or just walking the length of the studio? It may be an apocryphal tale but it is said that Brancusi began each day by sweeping the studio floor. Beginning at one end of the studio he would traverse the space encountering and cleaning the clutter of his past days work. By the time he reached the other end he was working, having slipped, without notice or loss of stride, into the mindset that shapes studio-time.

Studio-time is the practice of musing upon —becoming lost to?— the work of others, the work of art history and, per Brancusi’s studio stroll, the affective history of one’s own daily practice. It is a species of affective movement that oscillates between the centrifugal and the centripetal. Can we think of studio-time, very optimistically, as a regrouping of subjectivity and one’s place in history? Think again of Richter nursing German history through those blurs and forgettings to become, what, more visible, somehow more say-able or forever un-say-able?

For Simms movement and wrapping collide loudly in a series of works from the early 2000s. In these pieces toy cars and trucks stand in for big cars and trucks as well as being toy cars and trucks. In Red Truck, 2006, the toy is vintage, rusted, dinged and wheeless. In Mini Cooper, 2002, it is a yellow eponymous car; in Red Mini, 2003, a red one; while in Red Cooper, 2004, another red version of the car is crushed by a single huge stone (to scale, a boulder) with a child’s play ball attached above it all.

The concatenating device is the crushing. Like that giant cartoon foot from Monty Python; a huge pile of stones crushes each vehicle from above. The ‘scene’ is not animated, as in Monty Python, but freeze-framed as if from a YouTube video of the most unfortunate and improbable road accidents imaginable. Wrapping is strategically present; the stone pile is wrapped and then in turn wrapped onto and containing the vehicle in its wrapping. The sleight of hand here is that nothing is concealed. The calamities that might occur out of sight in other, larger wrapped-in-rope pieces, say, are here in the foreground. The tone is comic-dire. The old rusty toy truck exudes antique charm. The Mini Coopers sheen a kitchier plastic mien. All are crushed to immobility by the artist negotiating a semi-sacred ritual exchange between knowledge and loss.

Like all scavengers, Simms’s libidinous attention is drawn to the abandoned, to the flotsam, seeing in it unmet potential, unnoticed use value. The enigma of what it is that is wrapped, bleeds out and makes the wrapping itself enigmatic. A seemingly ritual act of concealment births a seemingly ritual object. In the foregoing a model –a toy car– becomes the vehicle of history, and wouldn’t you know it, it is rather difficult to maintain or track its movement. The train of history is derailed by Monty Python: perfect.

Where does that leave us?

So we all know things disappear. History disappears. Identity disappears. Simms dances a foxtrot around remembering and forgetting, around things being lost or even stolen and found. His things are hidden and disappear —almost. You could think of his sculpture as displaying a deliberately clumsy sleight of hand as a gesture to say, “I made something disappear, but reappear on my terms.”

History has no shape until we describe or write it (or sculpt it). Simms’s history of migration, scavenging, traveling, finding, losing, making is written into his corpus. “The hysteric suffers mainly from reminiscences,” said Freud (and Breuer). The collector is perhaps not sure what he remembers or forgets, not sure what is present, past or hidden, over there behind that other thing. But he knows he must collect.

_______

www.https://arthursimms.com/home.html

Loved this article and my artist and friend Arthur Simms. Brilliant writing and work.

We all have a Rosebud but you’re the winner.

Miss you.

Best,

H

i Love Arthur’s work. Profound and meaningful