Utopia in Red Light District

W139 was the venue for Now Babylon, a site-specific show that researched the topic of Utopia. The exhibition was curated and produced by New Sculpture Department (NSD), who invited ten more artists to join them for the occasion.* The title is derived from New Babylon, the Utopian project from the 1950s of Dutch artist Constant.

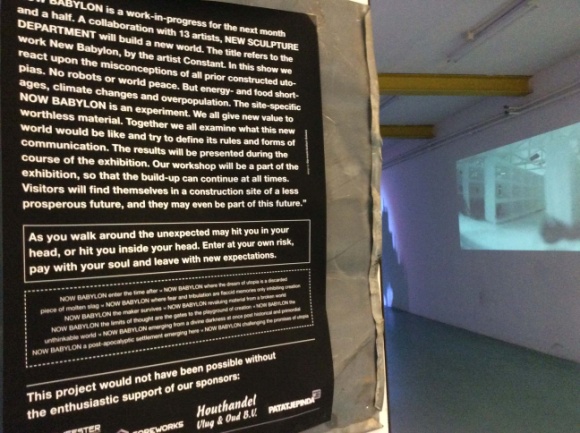

W139 is situated in a narrow street in the Red Light district of Amsterdam. I visited the show on a busy Saturday afternoon and parked my bicycle on the sidewalk near the entrance. In the time it took for me to lock my bike securely at least a dozen persons who passed by were caught off guard by a terrible noise close by. It sounded as if a ton of metal scrap had fallen from the roof onto the sidewalk, and one was lucky not to have been crushed. The interval between one sound explosion and the next one was too long for the startled individuals to be able to locate where it came from. A visitor of the show, however, would eventually understand that a big metal cube positioned right behind the entrance door produced the noise. The sculpture sent out a double-edged message: the sound was frightening if it exploded right behind you but everyone who had located the source chuckled at this contraption which flew up a few inches with every screech, as if startled by its own noise. Scary and funny. The double edge would turn out to be a red thread throughout this show and is one of the reasons why this was a fascinating exhibition. When I visited, the exhibition was under construction; it took shape while the gallery was open to the public. One felt the energy and the drive behind this project.

Inside, one continued down a wide corridor in which a video and more sculptures were on view. At the end is the entrance to a second space, which had a second level gallery alongside the walls. You entered this space “at your own risk”, said a rickety sign near the entrance gate. When I stood there I heard a soft voice coming from a cubicle high up and I noticed a gatekeeper inviting me to step forward, into what looked like a campsite, playground or wood workshop. It definitely also looked like an exhibition room. There were clever sightlines and the sculptures, tools, found objects, video, and sound interacted in surprising ways. One example was the connection that I assumed between four objects: a high wooden tower hovering a few feet above the floor; an observation post at the opposite side of the space; an open timber construction between these two which was suspended from the ceiling and in the middle of which was a chair; and three megaphones. The group seemed functional in an odd way: someone might be strapped onto the chair and would then face the tower, a second person might occupy the observation post and watch the chair and the tower; from the megaphones a third person might be giving instructions or admonitions or might simply be singing a song. I imagined a ceremony of sorts. Not a pleasant one by the way – chair, megaphones and observation post suggested an interrogation.

On ground level there was a makeshift coffee corner, a cosy nook with an easy chair and stuff to read. Above the café was a sign with large letters that spelled out NUKE EM. It reminded me of General Jack D. Ripper in Stanley Kubrick’s film Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb shouting that we must ‘Nuke ‘em dead!’ On a table was a book: Chanting Down Babylon by Dani Gal. Gal researched the plane crash in the Bijlmermeer district of Amsterdam which took place in 1992, and the impact it had on the residents, mainly migrants from Suriname and Africa. The two references in this mini installation: one funny and the other utterly grim, gave it a double edge. Ambiguity was indeed a crucial characteristic of Now Babylon. What seemed innocuous (coffee shelter; playground; smooth metal box) was also unsettling (reminder of a disaster; interrogation site; firecracker). Little was spelled out, much was suggested.

What does the exhibition clarify about its relation to Constant’s New Babylon? In 1978 Constant reminisced on his utopian experiment of two decades earlier: “At present the trend is extremely formalistic; the experiments are all purely formal by nature. Now, as opposed to the days of New Babylon, an artwork is almost by definition without content. And that is something I opposed. […] it is pointless and futile to fight for a purely formal renewal of art. I don’t want a new art form. But the time still isn’t ripe for the collective culture we thought was dawning in those days.” (Constant, Catalogue Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam 1978).

There are obvious parallels between New Babylon and Now Babylon, e.g. experiment, Utopia, collective culture. But similar concepts have different content. In Now Babylon I sensed a longing for Utopia rather than an ideology from which utopian ideals are construed. A post World War II mindset is indeed different from one that is framed by the financial, ecological and political crises of the present time. NSD’s project is less a radical rejection of earlier utopias, Constant’s included, than a redefinition: utopia is a work forever in progress, of which the inherent incompletion is not a sign of defeat but an open invitation to whoever wants to join in. NSD has a hands-on approach to artistic issues, in contrast to the more intellectual and theoretical approach of Constant. The collective culture that Constant speaks of is taken quite literally. Now Babylon is ‘the making of’ Utopia, so to speak. It is light and playful, and serious – homo ludens is the guy who is hammering alongside you, but he or she is very conscious of the plight of the present world – of “energy- and food shortages, climate changes and overpopulation”. If anything, Utopia will imply “a less prosperous future” and that in itself is not a bad thing.

For all its hands-on characteristics, Now Babylon operates as a (scale) model, enabling one to imagine a place, a situation, of wider scope. It invokes that place or its atmosphere – that is why here, of all places, I had to think of a traditional Japanese garden. It is in this metaphorical light that I interpret NSD’s message to the visitors of Now Babylon: that they “will find themselves in a construction site of a less prosperous future and […] may even be part of this future.” A critical observation in connection to the exhibition may be that it would be a non-committal gesture to build “a post-apocalyptic settlement [and to] examine what this new world would be like and try to define its rules and forms of communication” from within the safe confines of a gallery. But as I see it Now Babylon presents models of social behaviour. The sequence of tower – chair – observation post – megaphones is an example. Another model was presented in the video right at the beginning of the exhibition. One saw ant colonies scurrying through miniature corridors and walls of their dwelling. The formicaria were in fact scale models of locations around the world, sites with accompanying soundtracks of natural and manmade disasters, defining a new sense of the apocalypse. Watching the ants ceaselessly running back and forth I could not but see their activity as symbolic of human behaviour. Opposite this video was a proper scale model, a miniature two storey building. Nothing doll-house about it, it invoked a war zone, vandalism and abandonment. It was good that these two works as it were introduced the exhibition. “No robots or world peace” in Now Babylon. And no false romanticism either.

*http://w139.nl/en/article/22378/now-babylon/

quotes are from the W139/Now Babylon website, unless indicated otherwise

photos: Anouk Wouters, Dineke Blom

©Dineke Blom, 2014