Urs Fischer at the New Museum

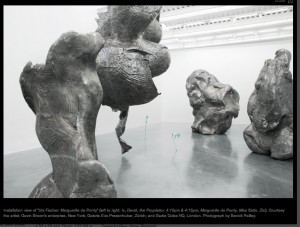

This is Swiss artist Urs Fischer’s first large-scale solo exhibition in America. That’s surprising in that, given the publicity that has surrounded this show, notably in the New Yorker, it seems as if he has been around forever. Perhaps the last gasp, until the deceased is once more resuscitated, of the profligate decade of overspending, typically bad-boy Fischer’s pieces take over three whole floors, as well as a small alcove in the stairwell, overlooked by many museum visitors. On the top floor, aluminum sculptures are suspended by chains, dangling only an inch or so off the ground. These large grey metal masses look at first like twenty-foot blobs, but closer inspection reveals the faint outline of enormous embedded fingerprints, as if some giant had flung off wads of wet clay mid-fumble and set some gallery walls around them. In fact, the clay was a mere bagatelle originally, a mindless rolling and shaping of clay between the fingers. The giant came onto the scene when they were blown up many, many times their size and cast.

Amongst these dauntingly large, organic-looking pieces is a larger-than-life plastic lamppost—melted a la Kippenberger, matte pink, looking like something from a twisted Dr. Seuss. Also nearby, easily unnoticed, is a low-to-the ground installation of a duffel bag and a birthday cake with feasting slugs floating above a subway seat. The cake spins as well as floats, in a sort of surrealist non-sequitor. What to say? The “if-you-see-something-say-something” suspicious package collapsed onto the more pleasant surprise of a birthday party, both ultimately leading to the inevitable end of an insect feast?

Moving onto the next level a real rotting, cucumber, carrot and hot dog prepare the viewer for a real croissant dangling at eye level, complete with real butterfly resting upon it, so small in the large space the unwary could easily walk right into it. Echoing the “drunken” lamppost above, a piano and bench seem to have deliquesed into an oddly matte melted tableau in lavender. The color is reflected and upgraded in the room, also a shade of purple, the gallery walls having been wallpapered with photographs of themselves. Outlets, directional signs, even air vents are all only two-dimensional images pasted right on top of the real thing. A portion of the ceiling, including lighting, has also been disguised by a flat version of itself. This is the famously and expensively lowered ceiling documented in the New Yorker feature, the demand which apparently confirmed Fischer’s status as genius.

Fischer has made fantastic use of this floor. There is the pure optical treat of the mutually enhancing purples of wall and piano sculpture; elsewhere there is a small punched-out hole in the wall. When a visitor gets close enough, a rubber tongue shoots out. Mothers and children yelp in surprise, gasp and laugh with embarrassment while security guards tote up yet another reaction.

The final floor is surreal beyond the others. Here Fischer’s attempt to “create hallucinatory environments” is made especially good. Mirrored boxes, covered on each side by huge and detailed photos of objects recorded from several points of view fill the space. Some images take up the entire box shape, leaving a greater or lesser mirrored margin. There are applied photos of decks of cards, VHS tapes, Dell computers—all larger than life, reducing the audience to an Alice-like tininess. Dozens of these pieces fill the floor, a refreshing twist on other “found object” art. Instead of lying on top of tables like artifacts, these objects have taken on new forms, blown up exponentially, two -dimensional on three -dimensional shapes, or vice versa, if you will. The show is involving, perplexing, fascinating, and best of all, a head scratcher.

Alexa Strautmanis