TALK TO THE HAND

Hands are well known for picking noses and pockets, giving fingers, reaching across oceans and the like. In the 1960s some were making peace signs. In 1968 one of Richard Serra’s was catching lead. It takes a little help from the title to grasp (sorry) what is actually happening. Off screen someone is dropping or tossing small, flat rectangular sheets of lead and on screen a hand rises to try and catch each one. Sometimes the on screen hand succeeds sometimes not. The on screen hand becomes increasingly dirty, one fears also hurt and scarred. The same action is repeated over and over—maybe 150 small rectangles of lead are tossed. At around three minutes, cut, it is all over. Serra’s early films (1960s – early 1970s) have always been more mysterious than his current breathtakingly greedy sculpture. In the shadow of such sculpture Hand catching lead (1968) feels pleasingly domesticated, particularly in this small screen presentation. But, and I suppose this is a very Serra thing, Hand Catching Lead still occupies a masculinly tough corner in this deft group show of nine artists at Lynch Tham.

Talk to the Hand is the show’s title. And there is much sense of action and gesture. Hands are making meanings, signaling things to other hands and non-hands alike. Carlo Ferraris in an untitled 20 x 22 inch digital print stations six figures, all male, all white, frat boys is the feeling, standing in a low walled courtyard, arms raised, index fingers pointing skyward, out of frame. The figures mostly wear summer shorts, two are shirtless; it feels like the beach is close by. And because we know not why, or at what they point, their gesture is full and empty, simultaneously. This is the device behind the show—isolating the gesture from the context. Does the gesture hold up, hold water, catch lead so to speak, or does it wander off down the viewer’s chain of associations. How strictly coded after all is a hand gesture? Words slip and slide along their confounding way, gestures too? Or, are the gestures more a rehearsal for the word to come? In this print Ferraris exiles strictness of code and ushers in conundrum. Partly because there is much else beside gesture—costume, location, performer, etc.—and partly because of the particular gesture itself. The performers seem caught in medias res as they make their gesture, maybe they have not finished yet. If in the next frame they were all to unfold their remaining fingers, they could be mimicking Kiefer mimicking the banned Nazi salute. So, gestures have boundaries to be cautiously approached. Tip the hand one way, gets you hello; tip the other, gets you a pile of controversy.

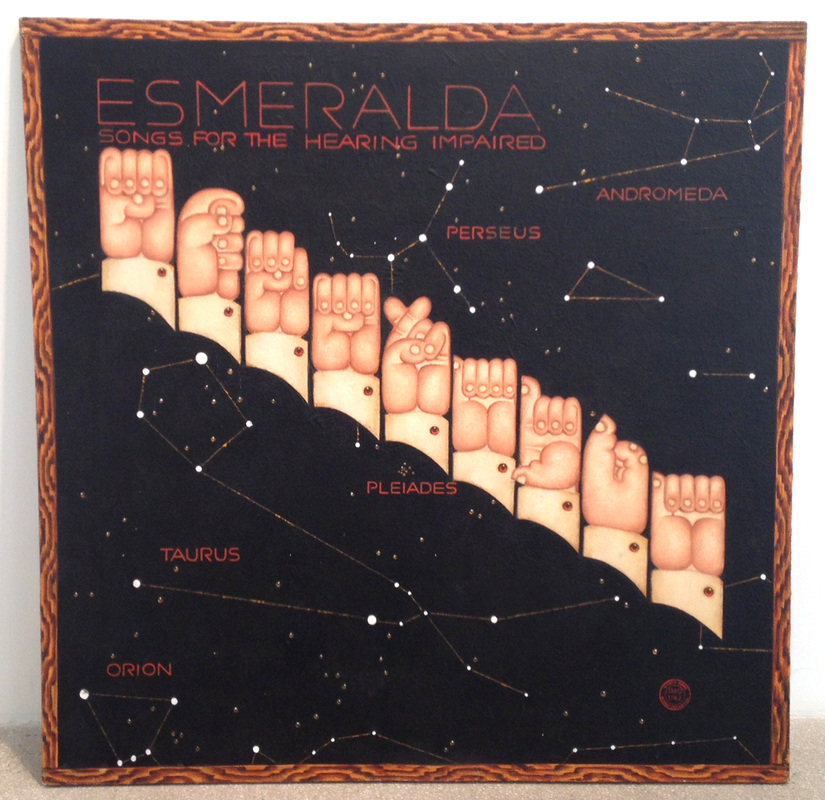

For a more solidly encoded sense of gesture’s meaning one might turn to ASL (American Sign Language.) And, as it happens, a show about hand gestures could do no better than include one of Martin Wong’s hand signaling ASL paintings from the 1980s. Wong’s self taught, painter-as-chronicler of a ferocious East Village, that has long ago been disappeared by gentrification, found time over the course of the years to generate an ongoing series of works based in ASL. Esmeralda: Songs for the Hearing Impaired, (1982) spells out, in highly stylized renderings of hands the name Esmeralda. It’s just a name, of course. Yet, one cannot help but think of Quasimodo’s love, Esmeralda, and her Gypsy bohemia as a corollary of Wong’s East Village life. Tragic, dangerous and unfair as the place—either place—was, one could imagine Quasimodo who was, of course, deaf, as one of the singers, or listeners Wong had in mind. Rescuing gypsies, or chronicling their lives, both were a foolhardy and often heartbreaking vocation for all involved. And all the lives here, both fictional and not, ended tragically.

Haim Steinbach’s sculpture is the most gesture-resilient or is that meaning-resilient work in the show. A shelf piece from 1990, it offers up two identical “female mannequin right hands”. These hands are presented blandly, foursquare to the viewer, found objects made of wood, as is their purpose built, veneer-laminated base, come shelf. Each hand has the fingers and thumb at very slightly different angles, almost unnoticeably so. One thumb is bent a hair more sharply than the other, but that’s about it to distinguish them. Looking on one fails to find Pinocchio-like life or ASL hints. The response to ones inquiring gaze remains pretty blank, there are no intimations of robotic life with the hands that are built to mimic real, “female . . . right hands.” Mannequins can, so they say, signal an uncanny presence of life, or a sense of death, which is supposed, too, to be uncanny. Yet Steinbach’s part-mannequin resiliently remains a blank and silent non-sign. Wooden fake hands rather than point, lead, if anywhere, downward with their wrists returning to the shared materiality of their wooden base, which is, as a veneer laminate, a kind of faux wood anyway. Un-realness absorbs un-realness back into itself. The piece becomes the foil to the notion of gesturing. It is the awkward moment of not knowing what to do with your hands. In the end what happens is, I think, that the act of presenting steals the show from what is presented. In that move gesture, as in a hand signaling something, is occluded, put out to rest, while the conceptual ‘gesture’ of the man behind the scenes is ushered forward.

Alona Weiss’ found object is a performance. A piece of political theater complete with cartoon wherein she finds the gesture—both hand and political—in Benjamin Netanyahu’s much ridiculed appearance at the United Nations in 2012. (Netanyahu was in fact there to talk about Iran’s nuclear program but he upstaged his political argument with his performance.) The scene is the one where Netanyahu’s finger points, jabs at the Looney Tunes-style image of a bomb grasped in his other hand. This whole affair is less about a singular hand gesture and more akin to a pantomime routine. It is all gesture and overacting, commedia dell’arte without the masks. Weiss returns Netanyahu to us in a small print on paper wherein she has protected the innocent or guilty by obscuring his face. The effect is to ham up the gesture, and that bomb, evermore. The faceless face and the bomb visually rhyme while the haloing effect of the ink on paper surrounds and seems to insist on pointing at the pointed finger.

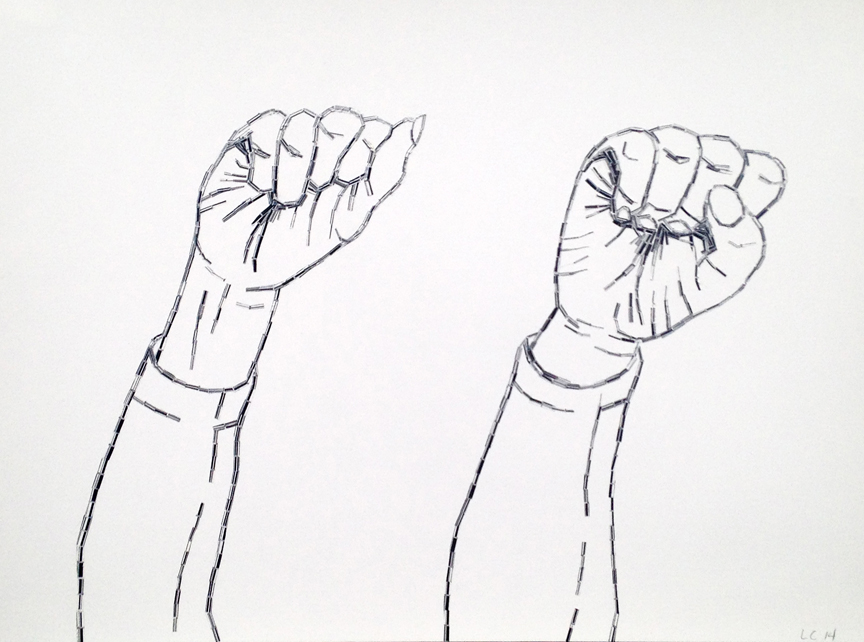

Luisa Caldwell assuredly works to undo the utility of the object she has found just about everywhere. Bar codes, in all practical terms useless to most of us, nonetheless, maintain a relentless authority over our lives. Caldwell, with a perversely retro technology, presumably an Exacto Knife, slices and dissects them to use as the means with which to draw. (One wonders what a scanner would read from these bar codes now?) Part collage, part line drawing the dissected bar codes are used by Caldwell to render two gesturing hands at the terminus of two forearms. If anatomy counts for anything the arms seem to belong, each to a different person (check out the thumbs). The work’s title, G and D, (2014) sent me scurrying back to check my ASL guide to find no concrete link there. But, that was a blind alley. Whereas, G. and D, the nonalphabetically organized letters of the title, are the real clue. Turns out that Caldwell is glossing upon a photograph, Dan Wynn’s 1971 all but agit-prop portrait of Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes to wit G and D. At first glance it seems like Trotsky disappearing from history at the business end of an airbrush. Caldwell is depriving the photograph—photography—of the naked thereness of its visual revelations. She is concealing the already revealed. But she is also positing that the photograph is merely the scaffolding for the gesture. It is a gesture to wave around beyond this historical moment in 1971 perhaps. Gloria and Dorothy offering their clenched fist salute to revolutionary struggle is a gesture not owned by G and D more than by anyone else. It is a gesture that can get freely passed around, all be it that that does not happen frequently enough.

Tracking close to 50 years worth of artists (from Serra in 1968 to Caldwell in 2014) who use signing, gesturing and gesticulation, Talk to the Hand comes across as a show that cannily talks about silence. The show does not propose that gestures constitute an actual vocabulary so much as it gives a nod or wave to the limits of words. Talk to the Hand posits hand gestures as—almost—a system for knowing when not to speak. Hand gestures are there when we know words just will not do the deed. Intuiting that the word’s claim to fullness will just get you in a mess of trouble one should have the smarts to fall dumb.