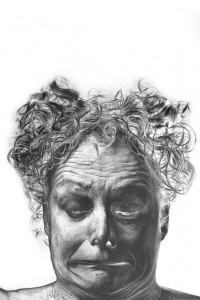

Susan Unterberg at 16 East 84th

No sooner uncoiled from the sock in the gut delivered by Susan Unterberg’s powerful new portrait photos—with their contorted features, hair literally standing on end, they are horrific, hilarious, inscrutable—no sooner recovered than the viewer is almost immediately besieged by a teeming mass of unswerving allusions, as difficult to shake as a mob of pursuing zombies. Therefore: madness incarnate or madness encultured? In effect, Unterberg has created a hybrid creature (heightening the frisson of monstrousness, all hybrids seeming at first unnatural), grafting the rhetorical onto the tangible. Mysteriously manipulated, the photos are like silverpoint drawings executed with a stylus scalpel sharp, every line of skin, virtually every cell and certainly every hair so distinct as to be reptilian. On the other hand, the theatricality of the facial expressions is clearly constructed. Mask-like in the sense of being exaggerated, frozen grimaces, the photographs recall a host of documentary moments in the history of the psychiatry/art nexus. Because it is the same face run through a sequence of emotional permutations, the set has the feel of a typology along the lines of Franz Xavier Messerschmidt ‘s bronze busts of afflictions, character traits and passing states or Gericault’s portraits of mental patients, commissioned by the psychopathologist Etienne Jean Georget so that his students could use facial traits to classify patients into various categories of monomania.

This leads us naturally to Charcot’s hysterics and the classic photos at Salpetriere clinic, a notorious topic for feminist work. As Hilary Robinson, among others, has reminded us, Charcot’s documentations were “staged,” and compiled images of different women with only fragments of hysteria symptoms so as to create a more comprehensible cycle for the clinical picture. And that brings us to the crux of Unterberg’s project. Although gender ambiguous, these are in fact self portraits, and, by the artist’s own admission, portraits about a woman aging and turning . . . demonic, unrecognizable, ungendered. (Mary Kelly’s “Interim” also connected Charcot and aging women, appropriating his words for the captions of her photographs of “hysterical” fashion items, but Kelly’s lingo is Lacanian and Unterberg’s lingua is franca.) Whereas Gericault seized on irrationality as a Romantic’s riposte to Enlightenment rationality, Unterberg’s investigation heads in the opposite direction, seeking to unravel the myths of the post-menopausal woman’s dangerous instability, although both artists share an anti-idealist stance. This is especially interesting in Unterberg’s case since her work has often submerged the grotesque in a species of classical poise. Her early probing of the unholy family romance of mothers and daughters and fathers and sons did this superbly. Since then, an interest in gothic subjects—insects, animal eyes—has often been balanced by cool palettes and compositions. Or by juxtaposing two antipodean bodies of work, as she did in the group of thumbs aping erogenous body parts paired up with a collection of pale moons in orbital eclipse. Here the cooling effect is provided, paradoxically, by normally revolting imagery—a set of photographs of jellyfish, signifying the unequivocally beautiful, pulling their retinue of silken cords and lacy, undulating ribbons. They float and evanesce like angels trailing beatific exhaust fumes.

Meanwhile, their luscious translucence contrasts significantly with the companion petrified images. Surely it is no accident that the vernacular for jellyfish is “medusa.” With their writhing locks and distorted expressions, Unterbergs’s head shots could not be more gorgon-like. Grisaille, the latter look to be carved out of stone. Masonry, dry point, etching, solarization—using the latest digital techniques, the works reference some rather outdated technologies, thus allowing the gender and age consternation to rap on the temple door of western art. Most pointed is the evocation of Man Ray’s experiments with solarization. It is less than ironic that so many of his portraits, often criticized as surrealist woman bashing, reinforced a highly constrained “feminine” and sexual ideal. Nary a middle-aged woman in sight. Catapulting herself into the similarly antiquated but still powerful role of the crone or the hag provides Unterberg some residue of oracular, vatic power, albeit as a sibyl who is also rather a cut-up. The overwrought Delphic cackling, “know thyself,” is tinged with a wry self-mockery.

Famously, the medusa’s head, with its nest of hair, is said to stand in for the female genitalia (no surprise that Medusa herself is seen as variously ugly and beautiful). Conversely, but in perfect keeping with Unterberg’s ungendering, she embodies both male and female qualities. Some women have adopted the image of the medusa as an emblem of their rage—and it is impossible not to think of Cixous’s famous 1975 tome, “The Laugh of the Medusa”—but Unterberg’s images may be more comically apotropaic than venting. There is the posing—as much like a child making faces as anything else–which adds a comedic touch. The restraining factor in the goofiness of this play is the fact of the subject’s age. She is no child nor is the role child’s play. The “vile bodies” of the funeral liturgy may not be actually visible, but mortality, senescence, and dementia are nevertheless the ticklish particulars, and their reality may be expressed in the hyper-vigilant inventorying of each individual strand and follicle. Ultimately, however, the artist purposely blunts any expression of fear or inner turmoil in these riveting works; she is deliberately taking on the archetype of the older woman. If Charcot believed that hysterics were defined by their susceptibility to hypnosis, Unterberg replies with a parody of the sort of contortions demanded by the stage hypnotist. She performs a valuable de-hypnotizing. She is wide awake.

Hans Georg Schneider