Pop goes the Easel

Pop Art and Its Progeny at the Lyman Allyn Museum curated by Barbara Zabel

by Howard Foster

There was never anything “gnarled” in Pop art. There was no matted undergrowth. Though there may or may not have been a rebuke of advertising, there was still always an unctuous mirroring of its perfect surfaces. And more than any of the other contemporaneous genres pop art mimicked the commercial world’s attitude to success: only the conspicuous counts, and money more than talks—it won’t let anyone else get a word in edgewise. This suave style held sway perhaps until Paul McCarthy and his student Mike Kelly came along with their gothic replaying of Disney and adolescence, when all that was loud, repulsive and hilarious finally erupted through the cool of Pop. (“What about John Wesley?” you are thinking. Quite right and given the revisionist thrust of the show—see below—it is surprising that he is not included. Well, you can’t have everything.)

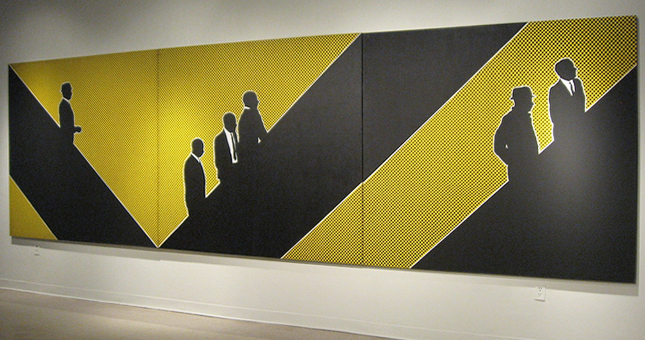

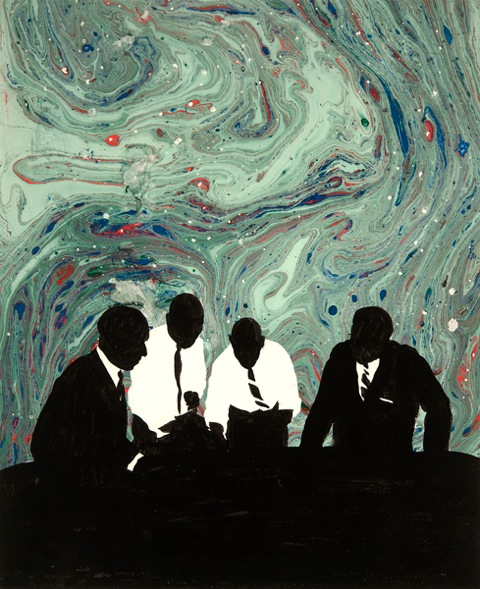

But to say that there was no visible underbelly in earlier Pop is not to say that there was no repressed. One of the really valuable achievements of this exhibition, curated by Baraba Zabel, is that it brings to the center formerly marginalized Pop practitioners—including, of course, women. Zabel focuses on four: May Stevens, Idele Weber, Marjorie Strider, and Nikki de St. Phalle. Of these, Weber is clearly of particular interest as she is represented by twenty works as opposed to one or two or three for each of the others. Zabel argues that whereas Strider and de St. Phalle adopted a male gaze, Weber kept her female point of view as she presents men “in their working environments,” their grey offices. The flattened affect of these anemic spaces is conveyed by the use of near silhouette rendering with patterned borders and backgrounds, a subtle domesticating and possibly trivializing of the subject matter. Sometimes the backdrop is so lively—as in one swirling, paisley, almost hemoglobal expanse—that the black and white featureless “suits” should clearly know real life lies elsewhere. Other times these “zero men” are limned against a checkerboard. One senses that Weber was having fun with concurrent art movements such as lyrical abstraction and op art, even minimalism, but in an odd way she also points to what would truly become the first movement to be dominated by women: pattern and decoration painting. Also prescient is a 1960 work, “Flower Girl,” not included in the show. It features the usual black silhouette form but this time of a woman, from whose flattened mound of Venus blooms, in full color, a blazingly orange flower. Still it is not always a withering gaze aimed at the men in the grey flannel suits, for in these pictures Weber often employs a frieze format to depict her monochromatic business men and as much as this suggests a sort of endless interchangabelness among the cast of characters it is also classicizing and confers dignity on them as well as creating an air of simple cultural observation, an uninflected recording for later civilizations.

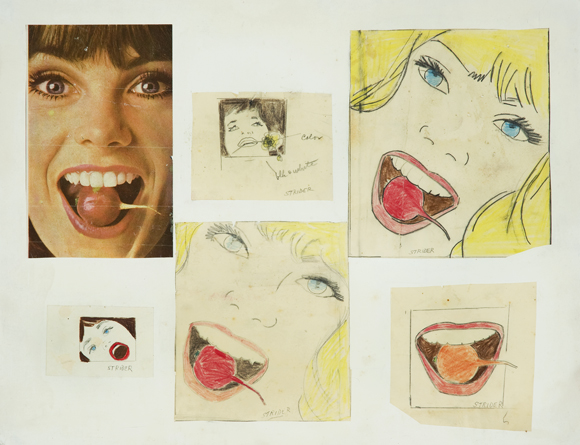

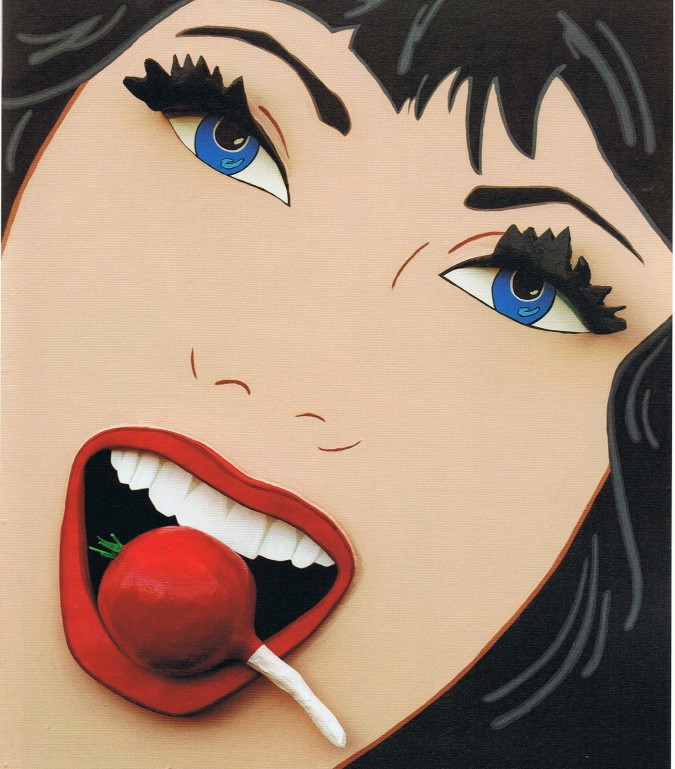

Zabel looks to May Stevens as the only overtly political female pop artist, although her “Big Daddy”—an impressively scathing work that makes the hairs on the back of your neck stand up — comes almost a decade after Weber’s, when “feminism, anti-war, gay rights and black power movements” have begun to unfurl their banners. Marjorie Strider, on the other hand, is represented by three works from the early sixties, before the support of like minds had organized, in the last days of unchecked sexism. Her “Girl with Radish” dates from 1962 and if you didn’t know better you would assume it was a Wesselman , as you would for numerous of her bikini clad and unclad girls, her open lipsticked mouths of this period. The curator claims that, like Nikki de St Phalle, Strider is showing how men see women. Putting a radish where some of her male peers would place a cheeky cherry is sly satire. Especially because it looks so much LIKE a cherry. But what is interesting is that, as time passes, Strider seems to pass up the sex for the food. She chooses the radish. All those receptively open mouths, those pearly white teeth, it seems, were hungry for something to chew on. So, what we cannot see here is how images of eggplants, asparagus, tomatoes, peas and peeled oranges take over in two and three dimensions. Along come works of erupted containment—a purse, a cardboard box, packages of Nestle and baking soda, all oozing an unidentifiable goo. The “slick” of Pop has turned to slime. The move to “low” domestic imagery, the concern with breaking out of confinement, and the ooze suggestive of bodily fluids point to another future woman-friendly style—the abject.

Zabel seems also to want to establish a legacy for these early pop artists and so includes works by Barbara Kruger, Carrie Mae Weems and Nancy Davidson. Of these, Davidson seems most at home in the pop category, her relationship to Nikki de St. Phalle being as strong as to Oldenberg. And with Davidson the interesting question of whether women should be “allowed” to appropriate a male point of view also arises. Having used her weather balloons for decades to depict the fragmented and fetishized female form, recently the artist has concentrated on the rodeo, a subject matter about as macho as it can be. So, first of all Davidson researched the matriarchal infrastructure of the rodeo circuit, thereby unveiling another repressed element. Her large balloon installation, “Let her Buck” is part of her “Cowgirl Dust Up” project. “The rodeo cowgirl . . . did things which were unacceptable,” says Davidson. This work comes closer to the parade celebration than earlier work does, which makes perfect sense since the carnivalesque has always been a draw for this artist. However, in recent exhibitions in New York, Davidson also included more abstract sculptures that seemed to bioengineer a saddle into a new life form or comically stretch out rodeo body parts—long legs, for instance—into a cartoon of bow-leggedness. Paired at one point with her sculptures was a video, “All stories are true,” a near documentary, but mainly lyrical look at male bull riders. Undue emphasis on the “maleness” of this film would miss the subtler point it makes in the context of the rest of the work. Here the male figure is subordinate to an actual stud, the powerful and dangerous bull, and the cowboy’s accoutrements—the fringe, the tassels of his dandified presentation—equate him with the corseted and ruffled inflatables Davidson calls her “daughters.” Meanwhile the bull itself with emphasized views of its buttocks and the graceful framing of its balletic manoeuvres also connects to the “girls.” Gender is made fluid in this most manly of competitions.

The other valuable contribution Zabel makes with this exhibition is to give a taste of how contemporary Pop manifests in its global appearances. What is Pop like filtered through the lens of Hispanic commemorative statuary? For this she gives us Luis Jiminez. Through the politics and style of Chinese poster agitprop,? The Luo Brothers. What is the new version of Chinese export porcelain? Li Lihong’s ceramic “McDonald’s—One Hundred Kids Play.” As with the contemporary novel, the recent inclusion of formerly subaltern cultures into the tradition gives it new vibrancy and relevance.

“Pop goes the easel” actually has nothing to do with the demise of easel painting which, at least according to art historical myth was accomplished by Abstract Expressionism. But who could resist that title, when, as Zabel points out, Pop art was expansive in ways that were not merely physical . It was “On the road” like Kerouac, and gave the kiss of life to a moribund portraiture practice– these are useful and pertinent observations Zabel makes about Pop. But, as already noted, it is the unearthing of the buried, the willingness to look closely at the overlooked, that is so very felicitous in this impressive exhibition.

Howard Foster