James Casebere at Sean Kelley

James Casebere has for a long time worked by producing photographs that are in close enough proximity to a photograph of the thing modeled, i.e. not the model itself, that we the viewer are left a-pause toggling back and forth between recognition and misconception. This is, by his own acknowledgement, that canonical modernist device of establishing a critical viewing distance from the experience. Over the past 25 years he has given not an inch, nor a tone, nor a prop more –nor less– than needed to situate one at this interstice where sign; referent and atmospheric lode prey upon one another. Even the elaborate enough plumbing alluded to in the flooded scenes from the 1990’s maintained an economy of means, of what’s there –just enough. With his new series of photographs, collectively called House, he’s –damn it– gone and moved to the suburbs and there’s a whole mess more to deal with.

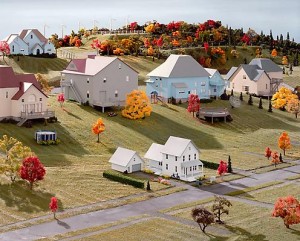

At the last Whitney biennial Casebere was represented by two large format color photographs. Far less claustrophobic, in any immediate sense, than his prior work these were expansive images of Dutchess County New York. They showed a wealthy suburbia of farms given over to subdivisions with Mcmansions littering the green and pleasant land. Now at Sean Kelley those images plus 4 more from the same suite are hung in the large back gallery. A selection of 12 earlier black and white, smaller images from 1978 through 1992 occupies the smaller front galleries and over all the installation provides a mini retrospective of Casebere’s work.

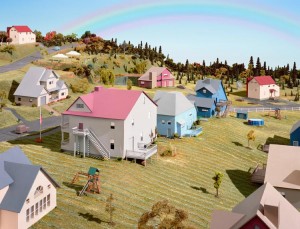

The Dutchess county images involve a newly spacious sense of architecture not just as site, but as sited in the outdoor – which is definitely not to say the natural –world. Thus there are aerial views. There are evergreen trees and deciduous trees. There are images that betray the season per the foliage color. There are backyard play sets and front yard flagpoles. There are above ground pools, trimmed lawns, pastel hued houses with roofs of many a pitch and eave, and there is even, oh Lord! a rainbow.

Despite the (artificial) light of day that Casebere is shedding on these models he is still dragging us where he always does, into an un-homely world of the scene feeling just right-just wrong. There are two reasons why the drag is less immediately apparent this time round. First, because the models Casebere makes of Dutchess County NY do, sort of, kind of, just enough, resemble the models a real, real-estate developer might use to trap us. They might be the actual pitch to our nesting desires. Second, and this is related to the first point, the models are as playthings of childhood, erector sets, Lego communities, fun little venues wherein to project ones wishes and fantasies. And so Casebere’s suburban scene does not become disturbing until we try to explain to ourselves the details, that is, the components of this idyll. Fumbling around in those fantasies, those projections of ours we come up against a hollow sounding question; what utopian longing can we, after all, claim to have seen satisfied by an above ground pool?

But probably I am wrong to frame the rhetorical question in this way. It is probably the case that the above ground pool, the manicured lawns, the many-eaved roofs in some reverse movement that has escaped me, activates utopian longings. It is perhaps the case that they are some architectural-sculptural-photographic correlate of the “useless details” of Roland Barthes reality effect. The useless details that; In Barthes words “seem to correspond to a narrative luxury, lavish to the point of offering many futile details and thereby increasing the cost of narrative information.” And in doing so here they narrate the cost to culture of a particular American utopia. Cutting ones way out of the thicket of signs has been a singular talent of Casebere in the past, where he pared down the architecture –the information– to bare whitewashed bones. Here the excess of information, lavish to the point of futility, turns ones head.

David Lynch dissed similar utopian aspirations of small town/suburbia in Blue Velvet. With time and elaborate plotting on his side Lynch assembled a catalogue of Gothic indictments that split the veneer of suburbia. Casebere does not go, like Lynch, for the lazy ways of surrealism or even the overly –er?– ‘Symbolic’. Even Casebere’s mawkish rainbow with its nod to Oz and a battery of hidden wizards does not really try to fracture the veneer. And that is the important, and I think, saving –over and against Lynch’s overwrought judgments– device of Casebere’s Dutchess County images. He lets the veneer stand. No grubs and bugs beneath (cf. Blue velvet) the trimmed lawns. The veneer stands but resonates emptily, without hidden secrets.

So were we paying attention? Well maybe not. Casebere wants to suggest a second chance of doing just that, paying attention. Awakened from the reverie of utopia’s pitch we might discover nothing beneath the manicured lawns; not beach, not paving stones just bupkis. But also Casebere has chosen to pay attention to the few embellishments and exaggerations he, or suburbia, has made. In this House is different from a lot of Casebere’s prior work where architecture that was, for sure, loaded with the heavy freight of imprisonment or institutionalization, squared off against the viewer. But it was also only ever the sign of said architecture. It showed the barest bones of resemblance to the space referenced. In House the models are far less, how should we say, shoddy, than they have been in the past. A seamlessness envelops House that is made all the more pungent by the absurdity of what is represented: a pastel hued theme park of seemingly topiarized houses adrift in mesmerized nature.

House brings to the foreground the manufactured ambitions of the petit bourgeoisie. As such we see that the accoutrements, the play-sets and flagpoles, the useless details of suburban life, hang themselves. Casebere’s masterfully choreographed rainbow is the final nail. At first glance the rainbow had seemed to me to be a sign too far. A slip up where the obviousness of the rhetorical gesture undid its power. But sitting with it awhile I came to relish its un-embarrassed perversity. Which end of the rainbow this is one can barely say. Besides we have never been let know what is at the other end of the rainbow. The one where there is no pot of gold. Possibly there is lot of firewood.

James Casebere

House

October 29 through December 4, 2010 at Sean Kelley