GREG DRASLER

There is a moment, if memory serves, about halfway through Godard’s Pierrot Le Fou, where his camera is following Belmondo and Karina as they scarper across the cliffs overlooking some gorgeous Mediterranean inlet. They are on the lam; someone is dead, killed. I do not recall if they are being chased, probably. Tension mounts, (that is, as much as either the viewer or the director of a Godard film will be invested in narrative tension) and, without cue, without warning, Godard stops following them. He allows the camera to track back, slightly retracing the ground it has already covered. He brings the camera to rest, to pause, overlooking the land and seascape. In the rush of narrative, we lost this moment of plenary bliss; the aesthetics of nature, coded by culture to be sure, are summoned to stall our pell-mell forward rush through narrative. For a short while we gaze, with Godard, upon resplendent beauty. There is a clue hiding in here about to how to think through Greg Drasler’s new series of paintings, titled External Drive, currently at Betty Cunningham.

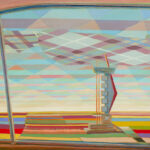

Drasler has, for a while now, as a painter visited the road. The road’s idiosyncratic byway architecture, its signage, rest stops, bus stops, its broad vistas and, above all, the automobiles that ride you past all of the above have been the iconographic mainstay of his work. These cars of Drasler’s, that hold the center of his paintings, they are not exactly fetishized but they nonetheless present with a curiously, ambivalent demeanor. Appearing somewhat disassembled they often convey a sense of stage sets or exploded diagrams of cars. Mostly they are models that predate the artist. They are elaborate ornaments from a mythological automotive past, objects of spellbinding elegance beamed in from 1940s or 50s Detroit, where they were voluptuously overdesigned. Typically, the car’s windshield or windows will operate as a framing device within a given painting. As such they situate a point of view, locate an actual or implied horizon, and give us a point from which the rendered scene is observed. Thus, a viewing subject, correlate to the viewer of the painting is inscribed within the landscape.

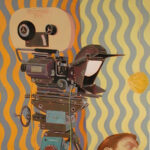

Much of this work has labored to reframe the road trip, allowing us to see, and just about hear, the artist’s conversation with Robert Frank, Jack Kerouac, Edgar Ulmer, Walker Evans (indeed there is a 2010 painting titled, For Walker Evans) and the meandering cultural thread they collectively wrought about the American landscape. Crucially Drasler’s images are assertively not about urban culture. They are about the territory, and its traversing, in between such destinations; and also, they are about how the aforementioned photographers, filmmakers and writers concocted what they did. An example: in 2015 Drasler organized a painting –organized in the sense that it is composed of seven 11 x 14 panels joined end to end– that is cinematic in implication via title, via frame-by-frame articulation and via –slap bang in the center– a close-up allusion to Hitchcock’s Psycho. The painting’s title? Bates.

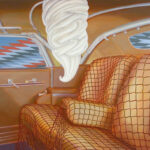

In paintings from around 2010-2011 the interior space of these/Drasler’s automobiles was vividly present; inevitably so, given, again, Drasler’s use of the exploded diagram device. These interiors forcefully showered the viewer with visual data, a whole stash of visual incident, novelty, and sign. Incongruous ruptures in the fabric of this realistically rendered interior space catapulted associations in sundry directions; a corn cob dangles from above, a swirl of maybe ice cream dangles center frame, a Speed Graphic camera (Walker Evans’?) lounges in the trunk. The corn, the ice cream, and so on, do not so much reveal or consolidate desire, or suggest conclusion, rather they obscure. Their disruptive presence credentialed though it as modernism’s favorite trope –or Surrealism’s dissecting table– flummoxes the wish to keep going, which is the wish of all odysseys and road movies. Thus, while nothing was ever actually missing from these paintings, indeed there was always a sense of overabundance, even too much, there was also always a deliberately engineered sense that something was amiss. And, while this is all going on, Drasler went on to render the lavishly upholstered and patterned automobile interiors that could almost sooth the viewer into believing in the promise of automotive luxury, said promise being the road movie of 1950s Madison Avenue.

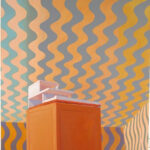

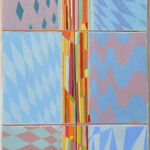

With the above as points of departure we can track a move/shift, in Drasler’s work, across perhaps a decade, perhaps a little more, where he steps –this is a very literal way to say it, I know– from the inside of the automobile out into the landscape itself. The work in External Drive gives us the broad vistas of the American open road. However, as if through entropy, they are collapsed into abstraction. From within the automobile abstract patterning, spawned from the textiles and xxx take on a life of its own. The seductive plaid interiors, the upholstery and fabric patterns within the represented space developed an incandescence that usurped the predicted photogenic lure of the American landscape. This is not an entirely new tack for Drasler, to some extent it is a strategy we can see as early as 2006, that is even before Drasler had taken to the road. A suite of paintings titled Wiggle Room presaged this threat that pictorial representation would ultimately be overwhelmed by abstraction.

In this newest body of work the abundant, and nominally, realistically rendered, patterning of the interiors is challenged by Drasler’s handling of what we might label the meteorological and agricultural patterning of the exterior world; the sky, the landscape of fields and pastures is, as it were, cloned by the automotive interior. And while abstraction, especially in the more vertically oriented paintings serially titled There and Back, (2023) could be said to dominate as a representational mode, it is still and always chewed around the edges by the not yet eliminated, never forgotten world of objects and images. If anything, there is a reciprocal chewing of edges –abstraction, pictorial image– as if each were hobgoblin to the other.

It is this chewing around the edges of abstraction and pictorial space that in many ways gives the work its intellectual heft. It is here that this question of point of view, of the observer, and the foundational effect of the representing of space for a viewer gets its workout. Remembering that the protagonist of the road movie (See Ulmer’s Detour [1945]) is the subject dislocated, the misfit, the social exile who is not psychologically or socially, or, in Drasler’s recent work, pictorially situated with a fixed point of view or subject position. We find ourselves at a crossroads where the whole history of the subject constituted in and through subjective point of view is set aside. Importantly, history is on Drasler’s side, many a road movie is not about a hero who finds answers to questions that provoked the odyssey. Rather the genre is often about an aimless wandering, a terminal dislocation for the protagonist. Few protagonists, after all, actually meet their sphinx.

Could it be that unsatisfied with what he finds in the source image, or the history of the American odyssey of the road Drasler just invents stuff? Is the iconography of the American road worn out? Probably not to both questions. There are amendments to be made, probably regarding both questions. Grace, perhaps lacking in the visual vocabulary of the odyssey, seems to be in the wings yet to make an entrance. (She’s been there for a while now.) Abstraction is as a redemptive angel hovering in the sky, and the fields, offering its service as a place amply able to absorb one’s projections. Anyway, it is not that Drasler’s images ever exactly careened across the landscape. Rather they cautiously, but assertively, reframed it; look just here, not there was always the suggestion. And, in following that suggestion, vision was abruptly interrupted. An apparition of a twist of ice cream, an extra steering wheel arrested both visual and, for want of a better term, narrative experience.

If the spectacle of the road beckons with a promise of something across the horizon, out of reach, then the mundane objects invoke the rupture between heroic odyssey and quotidian experience. The objects constitute glances of the everyday, glances away from the odyssey of the road. These objects do not vitalize the landscape, they confuse it, puzzle it. So, it is not the case that Drasler’s point of view ever really stabilized a scene, gave it to us as known world unto itself, available for us –after all, he is not a landscape painter– rather it wove the puzzles of perception, ornament, decoration, cognitive disruption, and lessons in art history into a wary tangle. If we hold on one hand that the logic of the odyssey or the road movie’s trajectory is forward, (remember the destination sign on Ken Kesey’s bus read “FURTHER”) then these seeping abstract patterns are like stoppages, interruptions of a narrative flow. Pauses on an implied narration through the United State which effectively ransack an iconography that, for the better part of a century, reflected the United States back upon itself.

This is where Godard sneaks in through the back door. That pause in Pierrot Le Fou, the abstract skyline, or the corn cob, in Drasler’s paintings, they are not exactly a stain on vision, not exactly pointing to another place of authorship or narrative law. But they are a way of refusing to play the game, they do sideline presumptions and rules about narrative flow, road movie logic or American iconography, all, I think, by being in awe of aesthetic bliss.

I think the experience for the viewer here is like tackling one of those hidden picture puzzles. The ones where you must identify all the animals hiding in the drawing of the forest. It calls for a shift in one’s experiencing of narration in cinema or in how one organizes visual knowledge in a painting. One toggles back and forth between differing modes, the whole picture and the hidden other pictures. And so, you get the beautiful landscape over the Mediterranean, rather than the narrative denouement, the abstract sky in lieu of America’s heartland. But can we welcome them in as benevolent intrusions that court a certain quality of visual pleasure? The sort where we are almost, but not entirely sure about what we are looking at.

So maybe we should dump Godard for now. Let’s talk about Nabakov instead. The line above, about aesthetic bliss, that’s his. It is from his memoir, Speak Memory (1951), and I think I am remembering this one correctly, in discursively addressing himself he asks, “Why write?” He doesn’t miss a beat. Prompt, concise, on the button the answer is “Aesthetic bliss”.