Ann Shostrum at Elizabeth Harris

Something has to be done about the acreage of camouflage fabric loose in this country. Thankfully Ann Shostrum has taken a shot at it in her current show at Elizabeth Harris. It is true –yes, yes, yes it is true– that, beyond the camouflage, there is much in Shostrum’s work that employs and highlights the traditional domestic and craft practices of women. And it is true that this has dominated the conversation about the work. Thus Shostrom deploys a broad range of fabric types which are sewn, layered, quilted, and embroidered. There is also a, perhaps less acknowledged, tempo afoot in the work in the way these fabrics are marked upon by means various. Wherein there is a frequent sense of soiling, of violence and of assault. Her wax-resist methods, for example, employ a blowtorch. And there are stains that allude to bloodletting. And then there are those bed sheets that will never, ever again be clean.

Interestingly, and inevitably I suppose, despite all the things Shostrom does to these fabrics as she works them over there is always the remains of the found image. That is, via the already existing pattern, motif or image printed on the fabric, a world of allusion or meaning resonates and is captured for the artist’s redeployment. And in this we get the feel for the artist as someone who trawls through goodwill stores and discount fabric bins –imaginative eye at the ready– for, now a scrap of scrim, now a remnant of floral giddiness, all to be stowed for later realignment in the studio.

An example: Framing Strawberries, 2009. While a decidedly atmospheric and abstract use of dyes, wax-resist, bleach, embroidery and paint upon a colored and patterned fabric lays claim to the greater portion of the work’s real estate, the left bottom quadrant is insistently a tangled feast of facilely rendered, printed strawberries tumbling from their punnets. This blatant retaining of the original fabric’s imagery, while surrounding it with a Ross Bleckner-like field, does more than the title suggests. There is a knock about fight between abject and carnal pleasures with each section of the work holding forth its rebuke to the other.

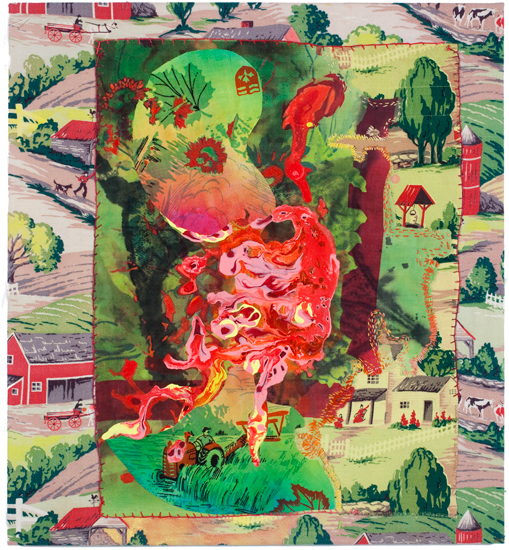

Again in Yield, 2010, the found images of the fabric print activate the surface of the artifact we are scanning. There are barns, horse drawn carriages, tractors and wishing wells that would make Grandma Moses proud. These images in turn frame another piece of found fabric with a similarly pastoral iconography blanket-stitched within the larger rectangle. The immediate effect is of a child’s quilt. Bucolic images, paired with stitching techniques and the overall scale of the piece, 25×23, readily assemble such associations for the viewer. And –curiously enough– the kitsch resonance of both the Framing Strawberries tumbling print and the Grandma Mosesey, Yield, is dispatched, left at the door as the traditions of quilting and the reveries of picnicking anchor our readings. Yet, rendered within the inner frame of Yield, through dying and painting, is an abstracted form of intestinal tracts, splatters, drips, drains and floral patterning. It is hard to fully say what is rendered here by the artist. The difficulty in reading, in this context, becomes a stain on vision. It operates as an obtuse disruption of visual knowledge and pleasure. We thought we knew what we had but we are losing our grip upon it. Assuredly it is not Holbein. It is not anamorphosis. But still it is soiled knowledge. It is as if, as we pin down what we think we know, what we have determined from a reading of women’s craft, fabric weft and iconography, that Shostrum tells us she is hiding it from our view. Uhuh! No you don’t! Go away. We’re in hiding.

Which leads me back to that camouflage. Much has been said about the relationship of camouflage to the practice of painting and to the formal devices of modernism and beyond. “It is we who invented that”, Picasso famously opined upon seeing World War I camouflage. And there seems to be a metonymic logic at work that says figuration jettisoned –or severely traumatized– by modernism, somehow conspires with human figures deliberately disguised to commit violence. I am not so sure that this is the filter through which Shostrum’s use of camouflage should be read. Or, more accurately, I would suggest that is one of the filters. Another –very, very, very importantly– is rural America. Because it is the case that Shostrum divides her time between New York City and rural Pennsylvania . To wit America’s happy go lucky cross hairs culture is her back yard. And it is the case that camouflage is the textile pattern of choice for much of rural, working class America’s cultural outings, aka hunting and ice fishing: (I swear on my parent’s graves I have seen this: men ice fishing dressed in full camouflage outfits.) When ‘camo’ is not about deep cover, when it is not about disappearing from view, when it is not about hiding from those dangerous deer and mackerel, what is it about? H’mm? I’m fairly sure it is ornament. An ornament of masculinity. And masculinity is the problematic trope of American culture that Shostrum introduce into a body of work cradled in “the traditional domestic and craft practices of women”.

Cubism refracted point of view. It is an oft told tale of the Twentieth Century dawning upon the realization –fostered by Freud, Picasso or Joyce, take your pick– that human subjectivity was in fact a little off kilter: decentered we have come to say. With the first major kill-fest of the century loyal or not so loyal (c.f. numerous mutinies along the lines on both sides) subjects of various crowns, republics and Duchy’s, thanks to camouflage, morphed into the foliage as if in a martial genuflection to the tropes of Modernism. The camouflage didn’t help them much as it all ended rather badly with millions left permanently morphed into the mud of Passchendaele and The Somme. Now, dawn of the Twenty First Century, camouflage is the mark of the NRA patriot. The very centered white, male, Republican subject. He knows his identity and it is pretty much an I’m-not-a-black-man-in-the-white-house-kind-of-guy identity. Identity’s coherence challenged again, this by time the wrong person being in the wrong place at the wrong time –though that does sound a little like camouflage– camo becomes the redoubt, the guarantor of stable subjectivity.

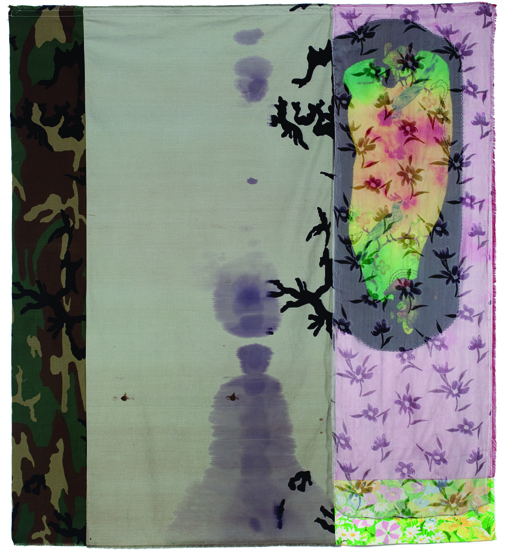

Satori, the Budhist term for enlightenment, is the title of one of Shoatrom’s pieces. Down the left border of the entire piece is a strip of U.S. woodland camouflage (Yes camouflage patterns have names). Down the right hand half of the same work is a wider band of vaguely ‘eastern’ patterned lilac fabric. Between, if not betwixt, is a neutral off white sequence of fabric with soiling, stain marks. The black camouflage splotches migrate from woodland camo at left to the Orientalist textile at right. Battle metaphor? Formal slippage? Neutralize one with the other? I don’t even want to pin it down. And, if it is not quite the smell of victory, we are seeing it is some kind of territorial spat nonetheless. If Camo culture wants to hide from the urban sissies and contagious, mongrel mixings that it fears, then Shostrum allows it a hiding place that, here, is feminized.

It is not that without the camouflage Shostrum’s work is just a museum of the traditional domestic and craft practices of women. It most certainly is not. But it is the case that by inducting camouflage into her formal repertoire she is starting a rumble. It plays out as a formal rumble but throw in a title –in the way artist’s are wont to do– and it shifts gears. Insurgency, 2006, one of the largest pieces in Shostrum’s show, edges the entire bottom section and half the run upward in the left side with a, perhaps, 8 inch strip of grey to white U.S. woodland camouflage. This strip halts the formal movement of the predominantly orange to black large panels it borders in a corralling movement. The entire piece is as a camo blanket for hunters –to wrap their kill in perhaps. And I imagine it no accident that a rural resident like Shostrum uses orange, or, in the lexicon of camouflage, “blaze orange” in the piece. Blaze orange in camouflage works to make the hunter visible to other hunters but, because most game animals are dichromatic –see orange as a dull not bright color– invisible to the prey. Shostrum’s deft formal lassoing of cultural signs draws the lines for a current generation’s so called ‘culture wars’. My prediction: it will be the rumble in the suburbs not the jungle. The camo crew are scared to go to the cites, the urbane too busy with, what is it? Chablis, to bother going out to the woods.

I enjoyed your thoughts about my work. You seem to know a lot about the PA half of my world. If you are in NYC, I am in a group show opening Thursday Feb. 17th 6-8 at Salmagundi Club 47 5th ave. (11th & 12th). It’s another camo piece, “Swansong”