Ars longa, divorce brutale.

I rode the subway. To see Robert & Ethel Scull: Portrait of a Collection that is. To have stepped onto the curb at Acquavella gallery, 59th just off 5th, and paid a cab fare would have been, well, tasteless. The Sculls have long been positioned as the Ur collectors of contemporary art in New York. And the drawn out and messy narrative of their lives together –and then apart– is often rendered as one of class ascension via collecting art. It is an oft-told tale of the crass, that would be Bob Scull, embracing the fine, that would be art, and in doing so demonstrating yet again the fungibility, thus irrelevance, of class in America.

Tom Wolfe told the tale perhaps not first and perhaps not best –but it was concise– in The Pump House Gang. Bob the working class boy from the Bronx/lower east side (his provenance is never clear) meets and marries the rich girl Ethel. Thereafter versions of the story differ in detail but, all take route through the parties of chic 5th avenue New York in the 1960’s, as the Sculls climb from rank outsiders of the WASP cultural elite to being hosts to scenes where Walter Di Maria and Larry Poons slug back the Champagne with Dean Acheson and Prince Michael of Greece. Along the way an enormously important achievement of the Sculls was to recognize, usually with an uncanny prescience, the work of people who came to be the important figures of Pop Art, earth art and kindred developments of the New York art world. They bought Jasper Johns in bulk before anyone else knew who he was. They sponsored Di Maria, and Michael Heizer in improbable sculpture projects. They commissioned work by Warhol, Segal and others. They gave artists stipends and developed relationships with dealers who would shape careers for many of the artists the Sculls anointed. Whoever is writing the story it always seems to stumble badly in 1973 with the auction of 50 pieces from their collection (the Sotheby’s catalog famously calling it his collection -you can see where this is going) that hauled in more than $2 million. Said auction and the stratospheric profits are frequently seen to herald the art-as-loot reveries of today. The train wreck is complete with an acrimonious divorce in 1975 and a brawl between the Sculls played out in the courts and in the press –who owned what art? – well into the 1980’s. The whole grisly affair is finally laid to rest with a court ruling in 1986 a short few months after Robert Scull’s death and about the same number of months before Gordon Gekko’s pronouncement on greed and America.

The exhibition space for Robert & Ethel Scull: Portrait of a Collection is itself is a paradigm of opulence. Acquavella’s townhouse galleries, a stones throw from the Sculls old pad at 1010, 5th feature a dramatic curved staircase, high molding adorned ceilings, tiled hallways and posh neighbors. It also tends to jumbles questions of fiscal value and intellectual or cultural worth by showing the work, with its given history, in the given real estate.

The dying shadow of, and I suppose the dying but didn’t yet know it art movement of, abstract expressionism is still there in this rendering of the Sculls collection. De Kooning’s, ‘Police Gazette’ (recently sold by David Geffen for between $63.5 and $135 million -depends who you read– to hedge fund manager Steven Cohen), Clifford Still’s ‘Untitled 1951-T, No. 2’, and a smallish Guston hold court in the front room of the townhouse. But fairly soon the installation gives over to what has come to define both the Scull’s collection and the relationship of the newly rich, at a particular historical juncture, to the art world: Pop Art.

John’s Target and map paintings hover not far from their abstract precursors reciting the history lesson of one brilliant mid century rupture in American art following close upon another. The Johns’ are iconic by now, the stuff of posters; a recognized shorthand for Pop Art. Iconic and popular in a way the particular De Kooning in question –unlike say the woman series- never was, and Clifford Still never would be.

It has always been the case that the subject matter of pop art –perhaps also that it in fact had subject matter– implied the possibility of a particular audience. It courted a certain visual literacy if you will. Here part of the Sculls story is relevant. That Bob Scull brought this particular artwork to the specific social milieu through which he was climbing is made much of by Wolfe and others. The climb, accompanied by such art, has Scull as a self propelled Trojan Horse travestying, in one moment, the tastes of Saville Row tailors (see Wolfe on this) and the cultural knowledge of the ruling class the next. In a way this is the story of Pop Art’s assault on culture writ small. It is that assault dragged very personally by the Sculls through the drawing rooms of 5th avenue. There are numerous reasons for the popularizing of culture from a historical juncture near mid century. But that the images could be so readily known is part of the deal. The images have currency. They circulate in a known catalog of points of reference. The Sculls just helped circulate them that little bit further up the economic ladder.

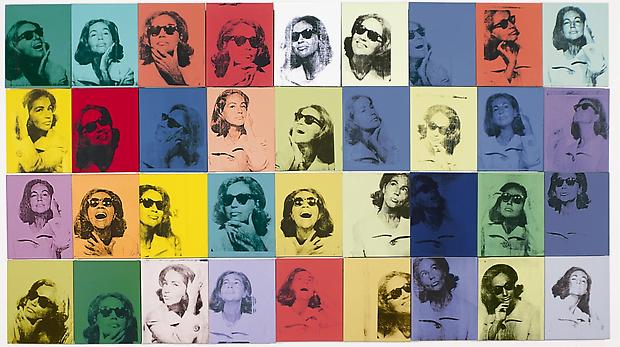

In the collection as a whole there is one artist/assailant who trumps Johns, in this regard of exploiting the recognizable. Unsurprisingly it is Warhol. There is a large, all but overwhelming flower painting of his. Two large –one pink, one red– very flat flowers (impatiens I beleive) grotesquely enlarged on a black and green scratchy ground; Pop icons that Warhol invented rather than borrowed. But Warhol is there most famously, and gratuitously, perhaps, with “Ethel Scull 36 times”. The artist and collectors were friends and Robert Scull, so the story goes, commissioned Warhol to do a portrait of Ethel. James E. Breslin, in his Rothko biography, tells how Warhol called to say he was coming over. “Upon arrival artist and subject hailed a cab” –they taxied no less– “to Times Square where Warhol put Mrs. Scull into an automatic photo machine and began feeding quarters into the machine”. More than one hundred images later Warhol is back at the factory generating a signature painting of 1960’s New York. It was the perfect date, the artist who was obsessed with celebrity and the collector who pined for it.

In an over the top show of excess, with a historical and gossip baggage of the same burdensome weight, Warhol’s air mail stamps catch the eye. The modesty of the work is the hook, and perhaps the modesty is all the more attractive in the immodest setting. It is work that is not trying to compete in size with abstract expressionism or Times Square hoardings (Rosenquist is here too). Modest in image because you cannot accuse it of cow towing to any celebrity thrill. It comes wrapped in what is in many ways a lost romance, that of travel and the mails. It hails from a time when air travel was still exotic and the missive home was an intimate relationship staged through yearning space and immutable time. Rather than the very brief tagging born of texting’s hurried truncations. It is the shows masterpiece because it refuses to be implicated in the grandiose dramas of the Sculls rise and fall. (OK, Oldenburg’s ray guns ar the other masterpiece.)

I’m not sure who is being rehabilitated here at Acquavella. I’m not sure who needs to be rehabilitated here at Acquavella. The snarky gossip mongering of the period up until the final divorce and Robert Sculls death in 1986, reads as a sad tale of what it meant to climb the class ladder in mid century New York. While the gossip column attention bespeaks an adoration of inequality overcome, even though that is largely a lie.

The Sculls, or at least their reputations, are easy to not like. And their paradigm of collecting as it pertains to today’s practices is not endearing. (Buy low sell high; ask Robert Rauschenberg’s ghost what he thinks about it all.). The title of the show – Robert & Ethel Scull: Portrait of a Collection– inevitably invites an appraisal of the Sculls as much as of their art. It, the title, wants to court a displacement of focus for the portrait away from the Sculls (and all the gossip) to their art. That the art will presumably give the more complex portrait of its era than the gossip will is perhaps the hope. But I think not. The complexity of the cultural moment is far more available in the relationship of the art to its moments of class antagonism, its moments of economic history, its moments of conspicuous consumption and its very many moments of narcissism. The show panders to the notion that to collect art is to enable culture and that culture, returned thus to the public viewer as spectacle, will mask the conditions of its production, consumption and circulation. It will not.

ROBERT & ETHEL SCULL: PORTRAIT OF A COLLECTION

April 13 – May 27, 2010

Acquavella Galleries, Inc

18 East 79th Street (between Madison and Fifth Avenues)

New York, NY 10075

212-734-6300 Phone 212-794-9394 Fax