Stephen Maine

Stephen Maine is a New York painter who lives and works in West Cornwall, Connecticut. His work has been seen recently at Odetta Gallery, Hionas Gallery, the Clemente, Westbeth Gallery, and Silas von Morisse Gallery in New York City, and at County Gallery (Palm Beach), Kenise Barnes Fine Art (Kent, Connecticut), Icehouse Project Space (Sharon, Connecticut), Calendar (Albuquerque), Five Points Gallery (Torrington, Connecticut), and the RE Institute (Millerton, New York). His solo shows have received coverage in ARTnews, Artcritical.com, the Brooklyn Rail, The New Criterion, and Twocoatsofpaint.com. He has received support from the New York Foundation for the Arts (2000) and Yaddo (2012) and is a longstanding member of American Abstract Artists and the International Association of Art Critics. Maine’s recent writing on art has been published primarily on Hyperallergic.com. He has been on the faculty of the School of Visual Arts, Parsons The New School, and Hartford Art School; currently, he is Chair of the BS in Visual Art program at Purchase College, SUNY.

QUESTION:

Increasingly you have given up the traditional mode of authorship and control of the artist. As you say in your note about the Residue Paintings, “conveying paint to canvas by means of a system that uses printing plates instead of brushes would save a lot of time and trouble.” You let a painting happen rather than willfully making a painting. The most extreme example of letting go of control is found in “Fire and Ice,” where the audience cropped and stretched portions of your room-sized painting. They made the final paintings rather than you. Your work is far from “deskilled,” but you have devised a way to evade mastery. Do you plan to go to the extreme of “Fire and Ice” again? How did that piece affect your studio paintings? How important is the evasion of mastery to you? As you play with a range of control in your painting process, how do you “work” at loosening the reins? Can you talk about your evolution as an artist in terms of how much control you exert over your work?

ANSWER:

The savings of time and trouble applies specifically to the process of conveying paint from my mixing pots to canvas. I micromanage the paint itself—its color (obviously), surface (I like a waxy sheen), viscosity, and opacity. I test samples of paint for those characteristics on small panels, and I then work with it on paper to better understand what I’m concocting.

It is true that I “let a painting happen,” but it happens as an outcome of a protocol that accommodates failure. By the time the paint is tweaked I have a small pot of it which, using a wall-painting roller, I slather over a printing surface roughly the dimensions of the painting. My “hand” is nowhere evident. With a minimum of finesse, I drop the wet printing surface down onto the canvas.

Procedural happenstance and the texture of the surface determine how the paint is distributed. The deliberate crudeness of this technique ensures that I don’t control aspects of compositionality (other than my palette). I like surprises; actually, I insist on them. It doesn’t matter to me how the painting looks, as long as there’s something there to look at.

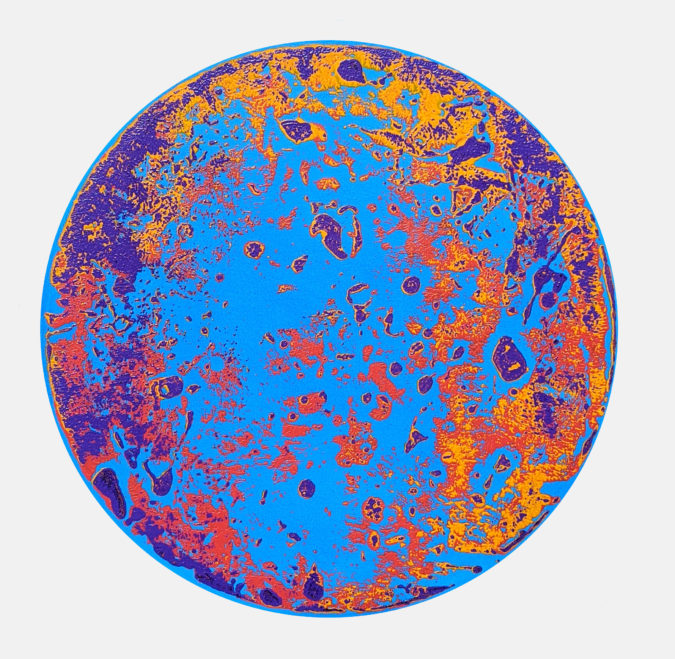

Once you stop worrying about doing things correctly, the possibilities are endless. “Fire and Ice” was a site-specific painting in acrylic on canvas, ten feet high and 45 feet long, lining the inside of a small wood-frame structure that originally functioned as an icehouse. The title refers to the two-part palette: diarylide yellow (which leans heavily toward orange) and a very cold blue I make by mixing phthalo blue green and cobalt Bermuda blue (a color I get from Guerra Pigments).

I applied the yellow in blotches and blobs to the blue field in my usual cumbersome way, using a contraption I made to print paintings that measure 125 by 100 inches. It’s literally too big to use properly. The colors sang, but the print quality just kind of mumbled. It looks good in photos, fortunately. Cutting it up on closing day was exhilarating. Anyone could take any section they wanted, as long as they brought the stretcher. It was like sawing up an enormous block of ice. We watched it all melt away.

“Fire and Ice” closing performance and cut-up party, Icehouse Project Space, Sharon, Connecticut. November 3, 2018. Photo: Katherine Manning

I recently did a project in Albuquerque that was designed to expand on the operating principle of e unum pluribus. The artist Jonathan Hartshorn, who’s been in Albuquerque for several years, often repurposes the gazebo in the backyard of his house as an exhibition venue called Calendar. For my show there, titled “Shrinkwrap,” I painted contiguous kite-like shapes in solid colors on a 35-foot-long plastic sheet, which Jonathan wrapped around the entire structure, even sealing off the entrance. He made it like a giant nightlight, with lanterns inside. The work was subject to the effects of weather, particularly the desert wind.

The idea was that at the end of the show, neighborhood kids could cut it up however they wanted and make actual kites out of it (or costumes, or flags) using sticks and string they’d bring to Jonathan’s house. I envisioned creative anarchy. The pandemic put an end to all that—the circumstances were beyond our control, ha-ha.

I like doing audience-participation projects, but they’re ancillary to the main thrust of my work. It’s interesting and fun to mount spectacles using prop-objects that qualify as “paintings” on the basis of their material fabrication, but collaboration doesn’t interest me as a long-term strategy. What with interaction of color, the figure/ground relationship, the spatial dynamics of the picture plane, and the neuropsychology of visual perception I’ve got enough on my plate as it is.

“Shrinkwrap” installed at Calendar, Albuquerque, New Mexico. March 28–May 2, 2020. Photo: Jonathan Hartshorn

So, other than the technical challenge of working on an architectural scale, I don’t think those projects significantly affect my studio work. I’m a believer in an art/life distinction; I quite like the “white cube.” On the other hand, if a project like “Shrinkwrap” motivates a kid in Albuquerque or somewhere else to paint his pup tent with polka dots or make a spaceship out of plastic bags, that would be great.

The flip side of control is chance. I’m attracted to the idea—Joe Bradley, maybe, did this—of dragging a raw piece of canvas across the dirty studio floor, stretching it, and calling it done. The conceptual implications of that procedure are profound, even though (and precisely because) the visual result is mundane. I’ve developed strategies to relinquish control of color, but because mundanity of color is so dispiriting, I haven’t made much use of them.

Several years ago, I read through the text of the Aeneid (Fagles translation), noting the sequence of named colors and color descriptions (e.g., purple sandals smudged with dust; night-darkened sails; tawny wolf), of which there are hundreds. I extracted them from the text to use in paintings. The objective was to compel myself to depart from habit and taste by outsourcing my palette to Virgil and Fagles. I like the idea way better than the paintings I came up with.

Part of the problem, certainly, is that language is inadequate to describe color. Saul Leiter told me he believed that, in a photograph, “something has to be in focus.” In the paintings I make, the color has to be absolutely deliberate, because the rest could fall apart. Color is the sun, and everything else revolves around it.

I love the concept of “outsourcing my palette”. Making decisions by not making them. Is there such a thing? In my youth I thought pot would help but it didn’t. It would be interesting to have a collection of artists’ personal stories on color. Just on color, what it means to us to work with color, its importance, how it has evolve in the course of ones practice and primary experiences. Well, carry on and thanks for your photos and the visit!