Kathy Grove

Question:

For many of us who have followed your photography over the years, the retouched images from the late 80s/early 90s are your most iconic work. Your fans have not had many opportunities to see much of your new work. How does your retouched photography from that feminist/appropriated period impact or inform your current work? In other words, what is the trajectory of your practice, as it may or may not relate to the earlier above mentioned work…if there is a trajectory?

Answer:

Broadly speaking my work has always been engaged with how an individual artist addresses the socio-political issues that govern our public lives. The personal is political. My aim is to address issues as an artist by covertly asking questions, not by overtly giving answers. Feminism has given me a frame of reference to take on the inequities embodied in the culture in which we live and mores with which we grapple. As a woman I am part of and apart from the general culture.

A trajectory implies a plan, a predetermined course. The work from the late 1980’s followed a path once the conceptual framework became clear. Prior to that project I had not worked in a series and now for the most part I work only in a series. Usually my path is not clear until well into the work.

As a child, every visit to my grandmother was an opportunity to forage in and cut up her giant trove of magazines and make new pictures. Those magazines ran the gamut of topics and points of view, from Life and Look and Time to fashion magazines, pattern books, knitting and gardening manuals and Sears and Roebucks catalogues. Her collected images became the means for me to concoct new scenarios and narratives.

Despite this background, for many years I rejected the notion of using photography as anything other than a way to be informed about the world. To me, photography was note taking, a means to an end. I took snapshots. I took pictures of details to facilitate my painting. I do not possess the type of eye essential to capturing the “decisive moment”. The technical information required to make a “good photograph” intimidated me and did not stick in my mind. I now think of myself as a maker of collages and gradually the way I made my living began to affect the way I made pictures. My snapshots and those of others became a way of linking private memory to a collective history.

Retouching became a more lucrative way to make money than my prior jobs. I had the necessary skills; the ability to mix and match color and to draw in a photographic style. I had been trained in printmaking, a respect for craft, and was temperamentally suited to detail oriented work. Retouching made me very aware of how women were used to sell us everything, even ourselves. Nothing was perfect enough. Advertising cynically made use of and re-enforced the very cultural norms that the women’s movement was trying to overturn.

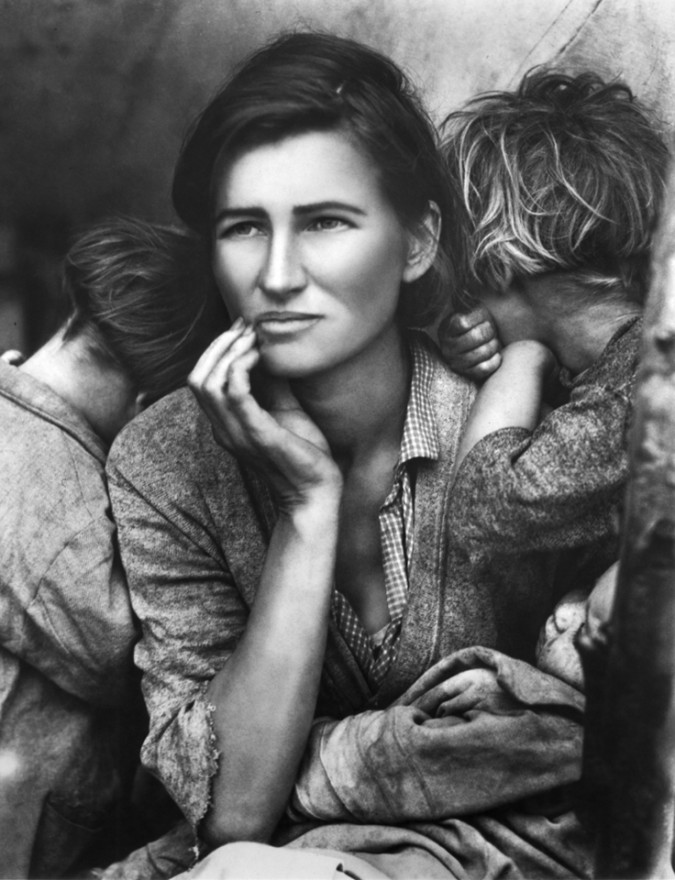

The Other Series was, in part, a reaction to and a result of the skills and insights I acquired as a commercial photo retoucher. It was a reaction to the way history is written, revised and engineered; a meditation on photography and its ostensible depiction of the truth, a reflection on the incomplete way we receive information and a political project that could address the construction of female archetypes as portrayed by artists throughout the history of painting as a representation of the natural order of things.

In The Other Series I chose to use the images from art history because they were a publically accessible record and had become the visual backdrop that formed a part of everyone’s collective unconscious in western culture. I used iconic images, images everyone knew, or thought they knew. They were seemingly very “clear.” What was enigmatic was specifically what had gone missing, what I made disappear from the image.

In Flotsam and Jetsam, I have been trying to layer abstract shards and fractured bits of contemporary imagery over private, personal images from my past or my extended family’s past. The newer works combines rather than removes information. In these, what has disappeared is the entire age that the images portray.

The internet has brought us all together but, in certain respects, it has blown us all apart. We exist as tiny disassociated electronic bits of images, scattered like chaff across a digital universe. It is as if we are all brought together to witness the visual horror and wreckage of the most current atrocities. We are offered up a heightened, unrelenting sense of mortality.

Almost exactly a century ago artists were trying to extricate themselves from the horror and wreckage of war and artists like Kurt Schwitters said that the effort, in both art and life, was to piece together a new world from the leftover scraps and wreckage. Today we seem to exist in a state of perpetual war, the locus of which is always changing.

Scraps, wreckage, and mortality mingle in The Outtakes, the works I compose entirely of the photographic wrinkles, cracks, and blemishes I digitally remove from fashion photos. From afar, they look abstract. At close range, the viewer sees the pimples, lines, dust, and stray hairs that were deemed unacceptable. These works, which are still about women and women’s bodies are related to The Other Series.

Human beings seem to crave certainty, answers and order. The public seems increasingly drawn to blockbuster action movies where scenarios such as they see daily in the media are somehow brought to successful closure. However, my work is more a “drawing from life” in that it will always be imperfect, incomplete and will elude closure.

For a number of years I have also been working on a flower series. Cultivated ornamental flowers, like art, have no overt practical purpose. They have been selectively bred for beauty. Flowers are most often associated with femininity, sex, decadence and death, which explains their universality as a subject.

Although they are inherently ephemeral, we scramble to keep them alive. We imitate them in wire, beads, plastic, paint, paper, ceramics, silk, et cetera. Flowers are used to commemorate and memorialize both public and private occasions. I have paired the flowers I photograph with silhouettes of the principals in political events from my youth to mimic the sanitizing and valorizing process that occurs as the body politic distances itself from catastrophe.

Rather than trying to control the fact that everything is impermanent, everything is imperfect, and that everything is incomplete, I want to highlight and celebrate the beauty in change and disintegration. I subscribe to Francis Bacon’s observation that the whole point of cut flowers is that we know they are beautiful and we know they will die.

One Question/One Answer is a series of very, very brief conversations about art and life between Romanov Grave and a variety of extraordinarily interesting artists.