Jennifer Coates

Jennifer Coates is an artist, writer and musician living in New York City. She currently has a one person show, “Carb Load” at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia which is up through July 17. She also has an article entitled “The Goo of Paint” in the current issue of Modern Painters.

Question:

Until several years ago you were painting lyrical works frequently composed of a lattice work of small shapes hovering in a nameless landscape-inflected space. Now, by contrast, your paintings are made using a clear, simple, bold, frontal composition, almost a non-composition. The shapes are big, practically reaching the edge of the canvas. And your subject declares itself without disguise as the all-too-pervasive junk food. While I am curious about the change of form and subject matter, as separate issues, I want to ask you about what, how and why it was necessary to fundamentally transform both form and content together.

Answer:

I love this question! It has many component parts to it so it might take a minute to answer…After working the way you describe for several years, I began to feel restless, and rather hemmed in by the labor that went into building these amorphous tessellations. I spent almost one entire year on a 4 x 5 ft canvas, nursing these little forms, painting and repainting their edges and getting them to nestle up against each other, all the while kind of hating myself for working that way. For months after that painting I stomped around angrily in my studio saying to myself “I need ideas!” I was looking for a way to be more specific and maybe incorporate humor (something that came easily to me in writing, but was absent from my paintings). I had also been doing all kinds of research into the origins of shapes and patterns, digging deep into the evolution of symbolic thinking in humans. I’d also been looking at structures that appear at all scales in the world and in the universe – including tessellations – trying to infuse concrete meaning into my obsession with certain patterns. Painting has to be about more than what my hands and body want to do in relation to the colored goo, it has to be a manifestation of consciousness somehow, or at least aspire to be that. While stomping around, frustrated, looking for ideas, alert like a detective, almost paranoid in my desire to connect seemingly unrelated things together, I had a series of revelatory experiences that led me to my current body of work that focuses on food.

Clipper, 40 x 30 inches, acrylic on canvas 2007

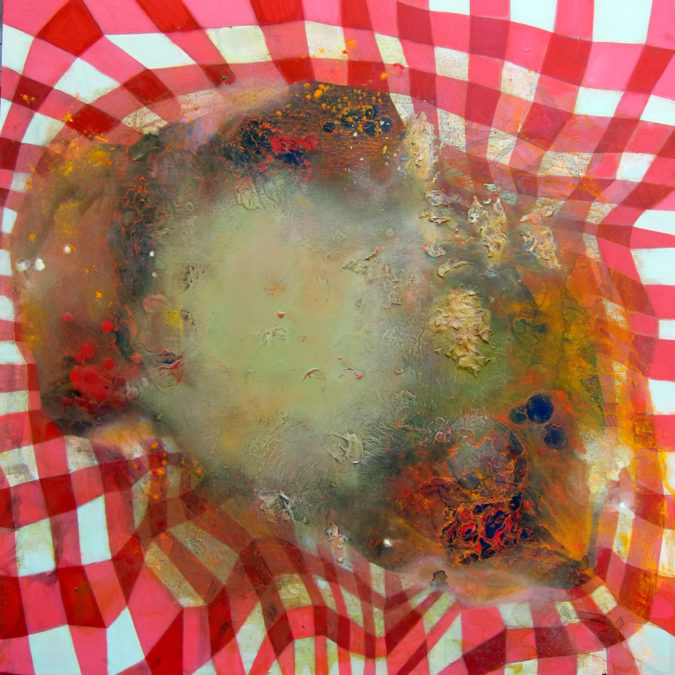

I visited Nicole Eisenman’s studio about three years ago. She had a painting in which several people were hanging around in a living room and there was this huge salami on a table. The inside of it was painted with all these little dots, a magical cluster of fat flecks and meat. She joked that I could have painted that part (another motif of mine in addition to the lattices was clusters of dots). That really left an impression on me. I thought how funny, a salami that looks light-filled and atmospheric, like a portal to another world. Then I saw Dike Blair’s vacation photos from Iceland, with its primeval, sublime, other-worldly landscape – the type of spaces I had been interested in evoking in my earlier body of work – but here they were interspersed with images of Dike and his wife, Marie, eating sausages and snacks by the side of the road at picnic tables. I thought, hmmm, that would be interesting to play with. What if the sublime erupted from something truly banal and everyday like…lunch? A few days later I was flipping through an Artforum and came across an image of a Claes Oldenburg sculpture of a typewriter and was blown away – here was something that was modern and recognizable, but looked ancient and like it had been dug out of the earth, made thousands of years ago. I started also obsessively looking at his early food sculptures. Something clicked in my mind. Maybe I could find forms that were recognizable but imbue them with a sense of something ancient and give them a radiant sublime quality as well. The recognizable everyday could be a portal back in time and through space. I had an unfinished painting in the studio – a warping grid erupting goo and spills – and I decided to just see what would happen if I painted a gingham pattern onto it, instead of this generic structure. So it would be in some ways the exact same painting, but be culturally very specific. I changed nothing about how I was painting, just anchored it to reality. The gingham did something really exciting – the erupting goo and spills, these automatist moves became stains on a picnic blanket and were immediately food related. The stains weren’t just abstract painting moments, they could carry content. While the food paintings I am doing now appear at first to be quite different from my older work, there is a continuity in terms of how I approach paint. I still sometimes pit very detailed, almost psychedelic patterns against more freely applied areas of liquid or oozing paint. I still use heightened light effects and toxic glow.

Blueberry Danish, 30 x 40 inches, acrylic on canvas, 2016

As for the shift in “composition” – I have always had a hard time with this word and what it means to make a composition. I have always wanted to get around it somehow. I have never been particularly interested in or good at the machinery of the picture. Marshaling forms and creating pictorial hierarchies in the figurative painting tradition is not in my skill set, let’s say. In my older paintings, I would make amorphous fields out of tiny marks, I thought of it as growing the painting like a slime mold, not constructing a composition. There was always a sense of something singular, monolithic, a phenomenon that pushes to the front while playing with ideas of deep space. It was always a singular event or hole hovering somewhere near the middle. In the food paintings I wanted to just embrace my aversion to composition fully and think about things like icons and idols, Paleolithic venuses, Neolithic pottery, ancient symmetrical shapes and how to merge my more abstract sense of space with the devotional object. The dumb object. The debased subject of food. Try to tease out my need for the sublime from that. It seemed more me, easier, more fun, funnier.

Picnic, 48 x 48 inches, acrylic on canvas, 2013

The form is now in support of content that more directly engages with ideas about the world we live in. Junk food is a problem for the gut and the planet and yet it represents the need for hand held transformational objects as well as easy comfort. Convenience food and its shapes and packaging is a descendant of portable rock art. It brings joy but also has menace embedded within it. To elevate the debased but pervasive junk food to an object of worship, an image of contemplation is to see within it the resonant forms that humans have always lived with – yet it is also to see its seductive and problematic nature.

The spiral is a pastry as well as a symbol in the caves. Cheesy sauce is a color field painting. A checked tablecloth is a Renaissance floor pattern. Convenience food, for me, is the convergence of art history, nostalgia and ecocide.