Cyrilla Mozenter

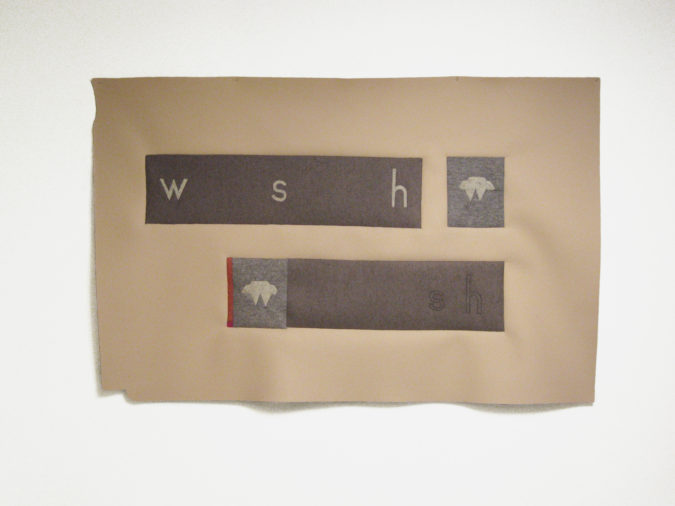

Cyrilla Mozenter is known for her gouache-painted, pencil-drawn (and written) works on paper and hand stitched industrial wool felt freestanding and wall pieces that include the transplantation of cutout letters, letter-derived and pictogram-like shapes. These works hover in the space between two and three-dimensions. Many of the titles and words that appear in the work come from Gertrude Stein’s writing. They are playful and absurd, defying singular interpretations. Solo exhibitions include See Why and the failed utopian, Lesley Heller Gallery, NY; the failed utopian & Other Stories, FiveMyles, Brooklyn; warm snow, Adam Baumgold Gallery, NY, and the Garrison Art Center, Garrison, NY; More saints seen, The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT; and Very well saint, The Drawing Center, NY. Octave, her bilingual collaborative book with photographer Philip Perkis, was published this spring by anmoc press, Seoul. A 2020 Guggenheim Fellow, she has also received two fellowships from the NY Foundation for the Arts and two project grants from The Fifth Floor Foundation. She has been in residence at Pianpicollo Selvatico, Dieu Donné Papermill, and Instituto Municipal de Arte e Cultura-Rioarte. Her work is in numerous public collections including the Brooklyn Museum and the Yale University Art Gallery. She taught for many years in the MFA program at Pratt Institute.

QUESTION:

Some of the felt shapes look like they are leftovers. After cutting out shapes intentionally you choose the remainder, the shape that happens after other intentions have been completed. The single letters are also a kind of leftover. A “y” can be used in “happy” or in “dysfunctional”. A single letter exists before meaning. Without spelling a word, a letter is outside of intention, a remainder like some of the felt shapes. How did you become involved with leftovers and remainders? What draws you to composing with elements that are before explicit meaning and circumvent intention?

ANSWER:

As a young child I drew with scissors, imagining hidden creatures released from their construction paper ground. This many years later, I am interested in both sides of the cut. Increasingly in the ‘other’ side because it subverts my expectations and puts me off-balance. My inner resources surface when I’m scared.

As a teenager I ice-skated. I liked to be at the end of a line of kids playing the whip, requiring an improvisational moment-to-moment attentiveness in order to maintain balance. The resulting lines incised in the ice constituted a mapping of the experience: physical drawing.

Letters are not the remains of words. I see letters of the alphabet as ideal forms with iconic power. They need to have lives of their own, aside from being ‘team players’ in forming words and sentences. I mouth their sounds as I work. (Wool felt, like snow, is an insulator and therefore quieting.) I am both performer and audience.

My works are evidence of the experience of making them. Nothing is not important. That includes quality of gesture. The gestures emanate from impulses that could be seen as alternately reckless and lady-like. I aim to be precise and unhesitant. I cut felt with élan and I stitch/stab with conviction. The quality of the cut is described by the resulting shapes on either side of the scissors. I can tell if the cuts or stitches or placements are good by sensing my gestures as I make them. I want to imbue the work with maximum energy.

The process of making my work is an adventure. I appreciate getting lost. I’m not interested if I know the way. If I don’t know either the way or the ultimate destination, I have to be very attentive to the subtlest clues that the process reveals. And to chance (help from the outside). I watch. What does the work want to be? What is it calling for me to do? Do I dare? What needs to be turned upside down, inside out or backwards? If I have pre-conceptions, I subvert them. I want to be surprised. I am, though, looking for a quality of inevitability. (A lawfulness.) That it couldn’t have been any other way, given me and my materials in that space and time.

Cyrilla’s narrative is informative and incisive –

like her art.