Matt Freedman at Studio10

Interview: Larry Greenberg on Matt Freedman with Tom Butter

Tues. March 9, 2021

How did you begin at Studio 10?

When I decided to open Studio 10 in 2011, my friend Adam Simon got Matt and some fellow artists together and met at the space. I got some beers, I didn’t know what I was doing, they were going to give me some guidance. This was my first contact with Matt. I was jumping into the deep end of the pool and I was trying to figure out what to do, it was a sink or swim kind of thing, very exciting. We all started talking and I realized at the end of this session that I would have to figure things out. I walked out of there more confused than when we started. The important thing was that it felt like everyone wanted the gallery to be successful. And that I wasn’t going to be doing it alone.

In that group, how did Matt fit in?

He was thought of as a person with experience and knowledge. He was a curator and an artist, he was respected. I have talked with people about some of the shows he did. There was this one he did called “Twin Twin”, it was right after 9/11 and first shown at three different locations. First at Vertec List, second at Pierogi, and third at Kate Teale’s space- Big and Small. This was before I knew him, but that was an historic show. People talked about that show as having the effect of “breaking the fever” after 9/11. I started working with him after that. He was the kind of person, if you emailed him, he emailed you right back. He made a point of coming to everything.He had a tremendous generosity. I don’t mean to exaggerate, but this is true.

This was part of his natural curiosity, no?

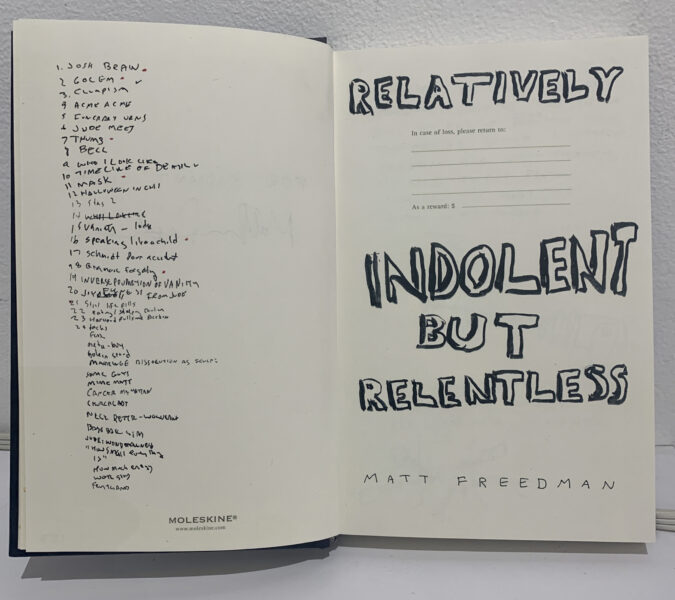

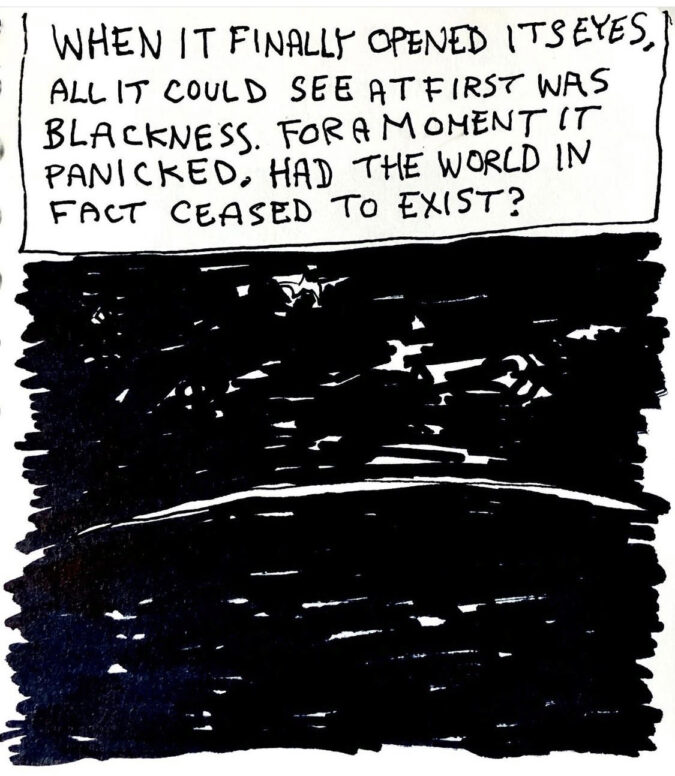

Yes but also he wanted to carry his practice out of the studio and be engaged with the community. He was very community-oriented. There was a reading at Studio 10, I was standing with him and Tim Spelios, and Matt said, “I have this pain in my ear”. This was late 2011 or 2012. He said he had talked to his brother, who is an MD, and his brother told him to get it checked out. Matt said he was going in to see a doctor in a few days. A week later I called Tim, and asked how Matt was doing. He was diagnosed with the worst kind of illness, he was going down that road. This was the basis for this book we later published- “Relatively Indolent, But Relentless”. The cure can be worse than the disease, medieval almost. But it did keep him alive, he had to go to Boston to get it.

Yeah He had a special mask he had to wear to avoid the radiation.

The mask and the other stuff involved with his therapy became art props, he talked about that. He integrated his experience, and filtered it, and came out with these wonderful uses for things. Some people hide under the covers and sit shiva. He didn’t do that. Matt would always ask, with everything he had going on, “How are you doing?” He would ask about you, it was remarkable! But if you asked him about himself, he would give you a full accounting. How he was feeling, what he was going through. He was totally open about his illness.

He talked about keeping up his calorie count, and resisted being put on a feeding tube which he ended up having the last few months of his life. Two years they say is the average survival for this illness, he went for eight. I think a lot of that had to do with his drive to keep going. He had a will. An amazing will. He was soft-spoken, didn’t seem tough, but he was fucking tough. To go through that, ugh, would bring down a lot seemingly tougher people than him. I had no idea what I would do in this situation. He would just say, “Well you know, this is what it is, some people breeze through others don’t.” For a while he was doing performances and stopping by the gallery. He made more journals. His condition kind of normalized, everybody said, “Well, he seems OK.” You can go back and look at performances recorded at Studio 10, and elsewhere, he looked great! Five years ago, four years ago, he was in good shape, high functioning.

What do you think the community meant to him as a totality? What was it like for you to be in his community?

There are wonderful people in this community, he was an outstanding member. He did move out into the bigger world beyond the arts community. I believe he knew many accomplished people with different interests. Around the time I was getting to know him I saw his “Golem” show at Fred Valentine. I was so amazed at that show, I thought, “I want to do this, I was almost jealous!” It was an incredible show. Definitive. He did a movie. The narrative was that they found the film in the synagogue purchased with his partner, Jude Tallichet. They called it “the gogue”. He did the film in black and white and it looked like it was made by amateurs back in the ’30’s. He had people dress up in period costumes. I was totally convinced, I thought, “This looks really real.” The mythology of the Golem goes way back. There is a famous story about the Golem involving a rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, a late-16th-century rabbi. Matt made it very convincing with props and sculptures, marvelous works scattered around the space. I was completely charmed by the experience. There was a set of dogs in a cave in the show that Matt told me was from the story from Diogenes: the cynic’s search for an honest man. The closest he could find were dogs!

My first show with Matt was “The Holiday Show“ in 2012. It was planned as open-ended play between Matt and Mike Ballou. Mike has a magical relationship with light and darkness. For him, Christmas is a joyous, wonderful time. I had the mistaken belief that because they seemed similar to me with their production and the way they thought about the world, that they would be a compatible duo. The show could be a collaborative event. Matt had just come from having his first therapy in Boston, his neck was a red as a beet. He was wiped out, but he insisted on doing the show. He was carrying boxes, and we kept saying, “Matt what are you, crazy?”. He didn’t even want to sit down. His will was so strong he just kept going, you know? He said this funny thing, about the sentimentality of Christmas. That the holiday was such bullshit, he really was aggravated. For the show he brought in a basket full of severed heads that were from a performance he had done about the French revolution and these monstrous little dolls. Also a rack of lights that go on the top of police cars. When turned on, the lights would pulsate and move back and forth. The lights were so intense they could set off an epileptic attack. Of course these lights over-powered Mike’s lovely twinkling lights and little motorized bags that scurried around. Mike pulled me aside diplomatically, and with empathy said, “You have to talk with him.” I talked with Matt, he took them out, he was cool, replacing them with these yellow warning lights, the kind they use on highways, they didn’t blink. But it was funny. It was a side of him exacerbated by his discomfort.

But also that he had an opinion about things, and he wasn’t giving in. He was fighting, both the illness and his limitations. People didn’t know what to make of the show but they loved it.

He spoke about thinking about how myths operate, and what is behind them.

Yeah, myths, big ones and small ones. With this show he wasn’t giving in. He was competitive, he wanted it to be real for himself, he was establishing his presence in the show even if he was only working at, say, 25% capacity. I thought it was a wonderful show: it was chaotic, full of magic. People came in and didn’t know what to make of it. They would shake their heads and say, “This is incredible.” It was one of the wildest things we had here. After the show, when things settled down, Matt was getting into a routine. But still he was suffering, he couldn’t taste anything. He had to eat to keep his strength up, it was very important to keep his calorie count and weight up. He came by with a copy of the illustrated journal he was keeping throughout the course of his treatment. It was titled “Relatively Indolent But Relentless” which was the medical description for the type of cancer he had. He asked me, “What do you think of this?” I looked at it and said, “This is amazing! We should do a show around this.” And he said he was happy to do a show but he didn’t want to do a show about a “cancer boy”.

So we did the show. It was called “The Devil Tricked Me”. We made 220 books of the “Relatively Indolent But Relentless” journal. Matt made a bookshelf out of 2X4’s that looked goofy and cartoony but also just right. It was beautiful the way the books sat in it. The show had 13 aspects of bad luck. There was a ladder you had to walk under set in the middle of the space, a cup of water with the Moon reflected in it. If the Moon’s reflection is visible in a cup or glass that’s bad luck. Esoteric stuff. He had a couch his father had used for psychotherapy, I think the original, or maybe be a cast of it. And on the couch was a hat. Also, the sailor’s warning about red sky in the morning…open umbrellas, etc. The image for the show was a cast hand holding the cards Wild Bill Hickok had when he was shot in the back: 2 Aces, 2 eights.

Matt’s intellect and curiosity were the most pronounced things about him. For him it wasn’t hierarchical, he was curious about everything. If you would tell him something about yourself or have a story to tell, he wanted to listen. Often bemused. It was always a pleasure to tell him a story. I only knew him tangentially before his illness. When he got sick we set a course together here at Studio 10. I knew him as someone who had cancer, from early on, to the very end. The way he dealt with it was by facing it. Whether it was death or simply the inevitability of the cancer, I don’t know. He filtered the experience by facing it as an artist. I think being an artist should make you curious. You want to know about stuff.

He didn’t talk much about his illness, although towards the end he became more vocal. I am going to make a guess here. There’s the subject, and the object, in life. If you take a step back and look at it. But the subject is the disease, it’s terrible to accept that you are going to die soon. There’s a due date, and a cost. We don’t know when. He was given 2 years, but he went 8, thank God. Still, 8 years is not that long. That was an act of will and an act of optimism, I think. Matt was a very physical person, very strong. He was on the crew at Harvard, a rower. That’s a tough sport, he was in great shape. This whole thing was the luck of the draw. I am thinking about when we were talking earlier. Even the last days of his life, before he started losing consciousness, he was illustrating and making up a story about a bear that becomes a fish. It was mystical, it talks about transformation in a profound, under-the-radar way…almost like a children’s book.

With mythological overtones?

Yeah. There is a smallish sculpture standing over here in the gallery that Matt made of a blue figure, with six arms each holding a skull, red lips, and what looks like a grass hula skirt, with a kind of bovine head and a gold Russian hat. The kind worn in winter. You see what it is but you don’t know what it’s supposed to be. It could be a combination of many things, like Shiva, figures from Tibetan Thangka paintings that are standing on skulls and flayed bodies, Bosch-like creatures, or some prop from an early Tarzan movie. I think the objects and drawings he made were intended to convey a narrative whether oblique or specific. It was humorous!

There’s another aspect of Matt: he was very funny. A lot of his work contained humor. His “Clumpism” manifesto, for example, was about being “deskilled”, not being “gummed up” or inhibited by technique. Even without the draftsmanship, which he had plenty of, his work always looked good. He had an intellect that flowed into his hands when he made work, it came through with humor and gravity. Maybe it was through struggle, maybe not, who knows? I would sit with him before the “Endless Broken Time” performances would start and he’d be drawing, it was so smooth the way it came flowing out onto the page. He pursued the ideal of being natural, of not being “gummed up”. But of course, he was so aware and knowledgeable about history, myth, and art-making that the idea of “natural” was very conscious. “Consciously natural” if that’s possible!

I think of him as an academic lecturing, but in a different way. Usually the lecturer has a blackboard, but Matt’s was on his chest…usually the blackboard is at a distance, it objectifies, but his is right on top of him…

That’s right, he wore it, drawing upside down, with a tablet hung around his neck…no laser pointer, ha. He was one with the lecture.

With a certain modesty, as well.

I don’t think he was modest, he thought well of himself, but not egotistically. He knew his worth and his strengths. He knew who he was. He chose to do what he did. He could have done many things, a person like that, coming out of Harvard.

Did he ever explain what being an artist meant to him?

No. My discussions with him were generally not intellectual. The kind of interactions we had were meaningful to both of us. I functioned as a catalyst that enabled him to jump off of, and then do stuff. I had the space and I was happy to have him explore and perform his work. I was delighted when he wanted to do something. I was always asking, “When’s your next show? Let’s do another one.” I was always pushing him along to do it. That started with his first show we spoke about called “The Devil Tricked Me”. We ended up doing 2 more shows and 50 or 60 performances over the years. He was very open. His profoundly curious nature, coupled with his intellect could be intimidating. Some people told me that. I never found him that way. It was just interesting to hear him talk, to be around him. And I’m curious, hopefully, in the same way he was. I think this is how one should be. He took things with people at face value, until proven otherwise, and allowed them to be themselves. Get through the initial stuff, find out who people are, and then decide if you are compatible or not.

This is maybe off-track, but in your case I sense a tremendous belief in the object as being a “final position” you take. You think a lot, but the object is where you stop.

Yes everything I think is held within the object. The process of making the object is interesting to me, the process of arriving at a place. Matt’s book (we spoke about it earlier) is an object. Arriving at the narrative, and containing it in a book, along with his drawing. That’s very much object-based. As are the props around the narrative. The performances are actually having the experience. Not something I would or could do, but something I found fascinating. Part of why I started this space was to find out about the unfamiliar. To satisfy my curiosity about how many ways there are to make work. What you do and what you’re curious about can be two different things.

Tim Spelios played the drums accompanying Matt’s performances. There was always a banter back and forth between them. Tim punctuated what Matt did with his speaking and drawing. They would start with a premise. “The Bee Dance”, for example, was about bees, but from that they could step off into a huge realm of subjects connected to bees. In another, he did a piece about “The 39 Steps”, the Hitchcock film, using “Mr. Memory”, a character in the film, as the subject. Matt made a tee shirt of the guy for his performance! I have one. As Matt spoke, there would be so much information involved it would overwhelm you. You can go to the website- endlessbrokentime.org – and watch what went on, it’s really interesting. It’s about how Matt thinks, totally. He’s not inventing a persona, he wasn’t like one of those professional storytellers. He wasn’t telling a story, it was something else. It was poetic, a stream of consciousness, it was encyclopedic. Mention a subject, Matt could spew information about it.

In March of 2015 Matt and Tim did a show at Studio10 called “Once Upon A Broken Time”. Matt produced like 500 drawings through the course of the show which consisted of a performance each week. Tim brought in 8 drum sets, one for each performance. After 8 weeks the space was covered with drawings and filled with drum sets. It didn’t look anything like what one would expect an exhibition should look like. People would poke their heads in the door and ask if this was a show. The performances started out as fun, engaging and ad hoc. Not thinking about the quality of the video recordings or sound quality. But, we did get serious, and with the expert help of David Weinstein we mic’d Matt and Tim up for sound.

The last year or two, Matt’s health was getting worse. Before the performances he would have trouble speaking, so much going on in his throat and eventually his lungs. He would be sitting here, preparing for the performance, planning on putting so much stuff into it, in his way that was encyclopedic, going in and out of subject matter. Everything connected, looping. When he got up to do it, Matt was transformed, he could project very well. There were all sorts of theories about that: getting up allowed him to breath better, etc. But I think he just was in the moment, everything dropped away, and he became one with the whole experience, with the subject.

You said when you met Jude and Matt they had a kind of glow or aura.

There was a kind of radiance coming from both of them. Jude is beautiful and spritely and Matt was tall with these black rimmed glasses. Cool personas. But they looked kind and approachable. Interesting, like people I’d like to get to know and connect with, which was unusual for me.

How about in art school?

In art school I was so young. And it was very competitive which turned me off. When I met people like Matt and Jude it felt like I was in the right place. These were people who thought like I do. I think a lot of different ways but at my core they were people I could identify with. There was a sense of authenticity, of being yourself, whoever you are or wanted to be. A freedom to invent, and reinvent. Also there wasn’t much gaming, we weren’t playing a zero sum game. There were possibilities for collaboration. Of course there were the artists’ egos but it wasn’t the kind of ego of rapaciousness. There was a sense that a synergy could occur where the whole is bigger than its parts. I wasn’t interested in being in front of Studio 10. I wanted to fill up the space with peoples’ expression. It was all about content. I got a lot out of it. If asked about getting into the art world I’d say, “Start a gallery.” My take on art, coming out of the NY Studio School was a mashup of DeKooning and Giacometti, which I still carry with me. I was only interested in painting. When I opened Studio10 my only criteria for doing shows was I had to be engaged in the work and find it interesting. No matter what it was, once I felt that way I was going to go with it, get behind it all the way.

With Matt, do you think that he presented you with a way of expanding yourself?

Well, he wasn’t the only one…but he was important. I could see the level of talent and ability out there. I thought, “This is low hanging fruit.” Also it helped that Bushwick became a center for artists and galleries. Deciding to show certain artist’s’ work or not wasn’t even a question. I could see right away, it was so clear. It was like, “Yes!” There were plenty of times where it wasn’t a “yes”, of course. But when it worked it was a gut reaction, it felt instinctual.

Matt was a leader among the people involved, right?

He had a following, people adored him. Tim Spelios loved Matt, and Matt reciprocated. I think it was very hard for Tim to lose Matt as a friend and collaborator. I think Matt felt the same way, he reciprocated. My relationship with Matt was work-based, doing stuff together. I knew him only as being ill, he had cancer from the very beginning. I was really fond of him, I enjoyed his company, his mind. I’m really sad about what happened. I think it is a tragedy. Sometimes I wonder if part of our coming together was a kind of fate. I served as something for him, in giving him this place, Studio 10, carte blanche, to use. Encouraging him.

Well for example, you suggested the subject of “bad luck”, that’s huge.

Yes I think so. He liked that idea right away, he was ready to go. People have said to me how important it was for him to have the opportunity to do his performances. It’s hard for me to take credit for stuff that I didn’t have much to do with, his experience resonated so strongly. We arrived together at a moment in his life, and I in mine, where I could do for him. But he did for me too, you know! It wasn’t one-way. I got a lot back. I loved doing it, I loved having the people here, I loved the attention he brought to the gallery. It’s not about the person, it’s about the project. That supersedes everything, it’s the most important thing- he understood that.

Matt seems to have occupied a very structured, analytic environment.

Yes he was a teacher, teaching was very important to him, that’s true. He was loved at University of Pennsylvania. Some of the memories students have are very moving. Students were inspired by him. There was room in his life for lots of stuff. His and Jude’s house was always open to people, they put people up. As chaotic as that place was, it was a shambolic place. Everything there was in motion, art everywhere. A tremendous feeling of art in progress, of creativity, ongoing. One piece taken out and looked at would be very interesting. He was a collaborator and a curator. He and Jude are the most collaborative people I have come across. I saw them operate together, it was always impressive. He would never impose himself, he had a very light touch. If you want to get involved, great. When it does work out, it’s very worthwhile. If not, that would be fine too. I took a little of that from him. I was open to collaboration, I was willing to let things play out, and not mess with it too much.

Matt chose the life of an artist, he could have done many things. This was what he chose to do. And he didn’t have the kind of success he should have had. He had all the ingredients. But why he made this choice has become clearer to me, now that we have talked about it. I have been thinking about what a fool’s mission it is to be an artist. I say that in a very respectful way. I’m involved in it. But think about how much more meaning art has than a numbers thing, or a quantitative thing. He chose to continue working during the last days of his life, to continue to make these drawings. Jude said that as long as he could keep drawing it was worth it to him to stay alive. It was that important. There are many things you can’t control in life, but there are some things you can control. Realizing your fantasies is one of them. You can make it the way you want to make it, and insist on it being that way. You don’t have to answer to anybody.

Matt’s choice involved being realistic about how and where he could be most effective. Even though he was dying, and not knowing what would happen with his stuff, he was driven to make these drawings. On one hand that seems really crazy, and on the other, it seems optimistic, really great. It goes to the absurdity of it all. A beautiful position of absurdity. I think Matt’s life, and his subject matter was about a beautiful absurdity. That’s the best thing I can say.

A great tribute to a great artist. There’s a lot here that strikes me as profound and makes me think about being an artist a bit differently than perhaps I ever have. Kudos to Larry and to Tom Butter for making it possible. Matt and I were once tasked with curating an exhibition for a university gallery. We couldn’t come up with a cohesive statement about what we were going for, no elevator pitch, but we had fun imagining. The show never happened.

Loved this, Larry. The memorials have looked at Matt from literary, historical and sculptural angles so far. With pictures and spoken word, we find Matt’s best and highest form.

Thanks to you and Tim Spelios for keeping Matt going artistically in his final years. If you provided the opportunities, Tim provided the discipline. Watch “Thrush” from 6/28/20 to see Tim in his role as full collaborator.

Thank you Larry and Tom for this beautiful remembrance regarding Matt, and much else.

I want to share some thoughts I jotted down last year about my meeting Matt. He was

unforgettable, he touched us all in profound ways.

I met Matt for the first time in the late 1990s. He was teaching at Penn and looking for a NY teaching gig.

Parsons, where I taught, seemed the right fit. My friend Jackie Brookner (also deceased) introduced us. Matt

and I had lunch in Chinatown. He regaled me with stories about the Synagogue, Jude, his dog.

He was one of the most kind, original, delightful people to have ever crossed my path — and funny,

very funny. He taught at Parsons for a number of years until there were some drastic changes in the

personnel at the school. All very unfortunate. He was missed.

He became sick, I gave Jackie the book her wrote on his illness as I sought to console her while

she was sick. For a long while I would see Matt at events, including a “We Make America” demonstration

at Castle Clinton. And, of course, at Studio 10 for performances.

Generous to a fault, wildly original, smart, very smart, creative in art and life, illness and death.

We miss him already so much. He showed us the way.

Thank you Jude.

Lenore M.

This was a wonderful, moving thing to read. Thank you for it. Matt was a dear friend and we miss him all the time. I learned a tremendous amount from him, as so many did. He understood the importance of accepting whatever limitations where at hand, even finding ways to work within those to incorporate them into the very framework of what he was doing. And he carried the flag for many of us who believe, artistically, that humor is one of the most vital and serious tools one can work with as an artist. Exceptional role model.

We love you, Matt. I hope there are some nice cats and dogs and an unlimited supply of Sculpey wherever you are nowadays.

Nina