Brian Gaman

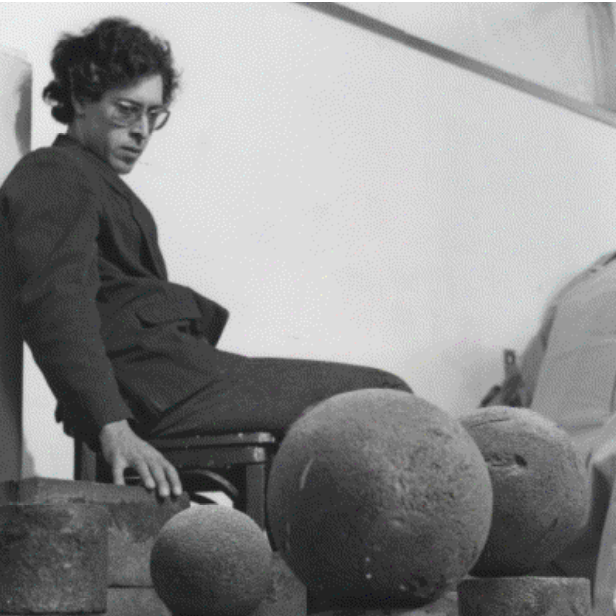

In 2014, Brian Gaman, one of the founders of Romanov Grave died. We miss his exacting intellect and his rigorous vision for art but hope this page will help us and the art community remember him. A friend of his once said he was a fringe dweller. It turns out fringe is the place where inventive art is produced. As Terry Sultan has written “Although [Brian] left us too early with his unexpected death in 2014, his artwork and intellectual acumen remain as his legacy.”

JEEPERS, CREEPERS, AND PEEPERS

by Jeanne Silverthorne

Brian Gaman once tried to make eyeglass lenses by casting the glass himself. They cracked; he left them unpolished. He kept the bridge and arms off the frame, leaving just two black-rimmed circles. And, oh yes, did I mention that he made them nearly two feet high each? They lean casually against the wall. You would never guess their true identity. Likewise another pair of spectacles, also from the late 1980s, just as impaired, with a cataract of nylon mesh across the lenses. This time the frame is complete but disguises itself as a Jean Prouvé–style bench or coffee table. The steel legs fold under and in, the structure ready to be put away or taken out of a hypothetical carrying case. All these clues to its identity and still this shape is slow to announce itself as eyewear, nor does the title allude to such a thing; nevertheless, once you “see” the sculptures as pairs of glasses it is like the hag in the drawing of the beautiful woman—that old chestnut of a perceptual double entendre. Easy to miss, but having seen it you can’t unsee it. So, too, once you take in Gaman’s blinkers, the ghosts of Harold Lloyd and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s T. J. Eckleburg, the optician whose sign hangs over the famously symbolic ash heap, never depart from Gaman’s work. Comedy and dread, inextricable, an aversion to certainties and warranties, produce what Alexander Nemerov has called “an existential standoff.” These works, despite their shy claims, pun on Gaman’s long-term goal, to enlarge the field of vision. Trouble is—like all the best artists—Gaman was bedeviled by a dybbuk of doubt. So everything attempted had to be undone or effaced. Sometimes you can even spend time watching the vanishing, as in the 1970s video he made tracking the shrinking into a dot and subsequent disappearance over the horizon of a friend running away into the desert.

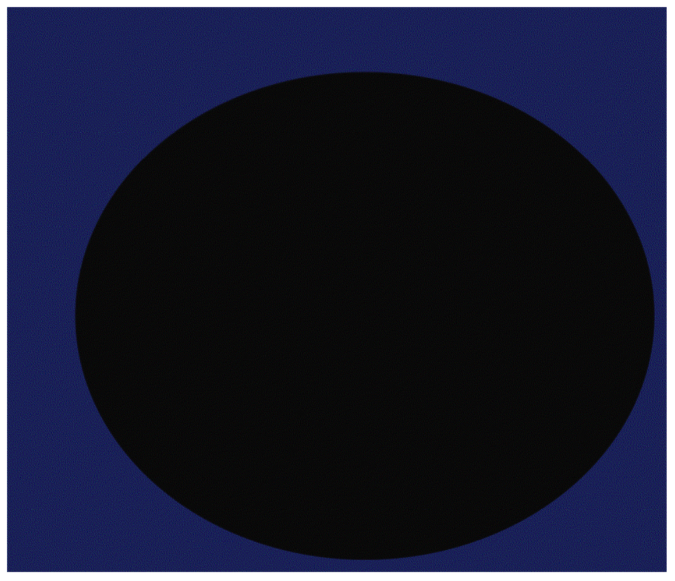

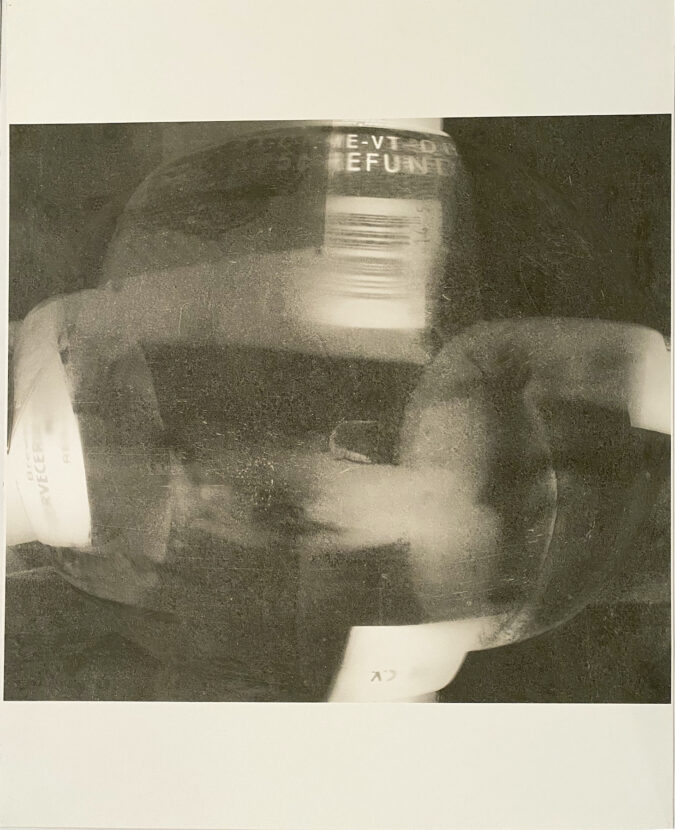

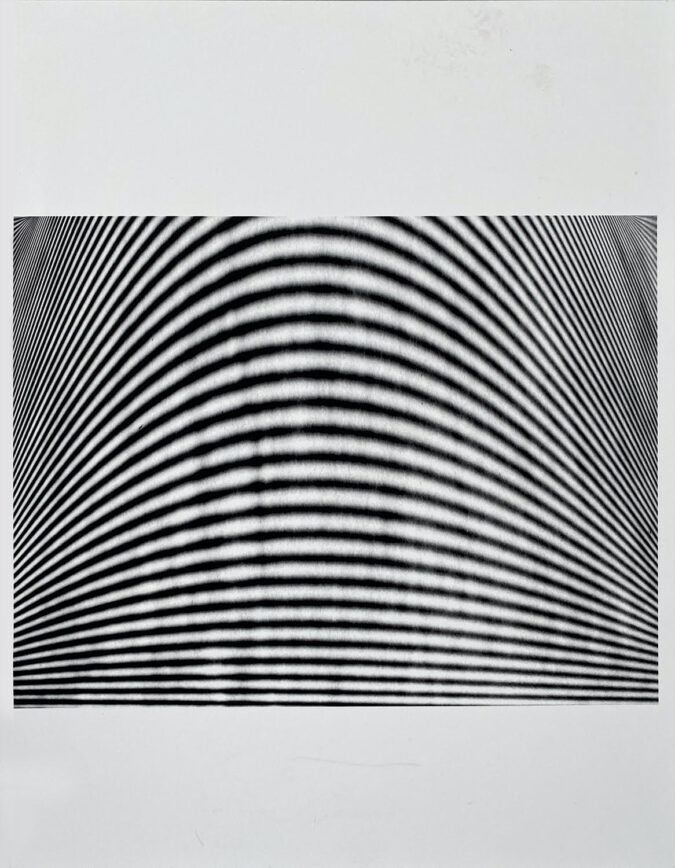

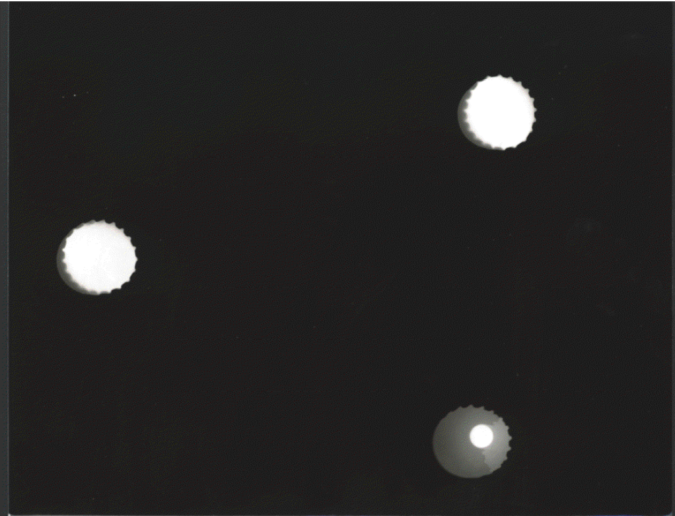

Dots and circles are everywhere in the work—floaters of shortsightedness or spots in front of eyes strained by looking into the sun. In grad school at Yale, Gaman was interested in artists concerned with the gap between knowing and saying. That means neither knowing nor saying. So the work is terse bordering on mute—hence the difficulty of discovering that occasionally those spheres are actually bubbles of hilarity, hiccups escaping from a Beckettian black humor hole. Indeed, inebriation is the genesis of pieces from the late ’90s. Having made a series of inverted tables, including one with a ROUND aluminum cup for the gum that would normally be stuck underneath, he developed a “parallel pictorial item for what would happen on those tables.” He put beer bottles on photosensitive paper, scanned in the image to files, and enlarged it to 36 by 44 inches, in other words, expanded the visual field to the threshold of incomprehensibility. Blind drunk. Not to mention that beer bottles leave rings on tables. He is literally making a point, or a series of points. If the point is warped by, say, its own peripheral vantage, that’s part of the fun: When is a point not a point? Ultimately, however, with a silver print photo of a black circle, 50 by 94 inches, distorted so that the edges go in and out of focus, the humor has dried up to a speck and blown over into the land of minimalist gravitas.

For a certain generation of sculptors, conscription into the minimalist army required some deft draft-dodging. Gaman’s strategy, not surprisingly, turned out to be a sort of neither/nor impulse: neither the ephemerality of Irwin’s optics—despite an ongoing concern with opticality—nor the clenched fist of Serra’s panzer brut, despite the heavy use of iron and often rusted steel. Instead he produces a “strong misreading,” an ironic collapse of antithetical terms, rendering the iconography of ethereal perception in iron.

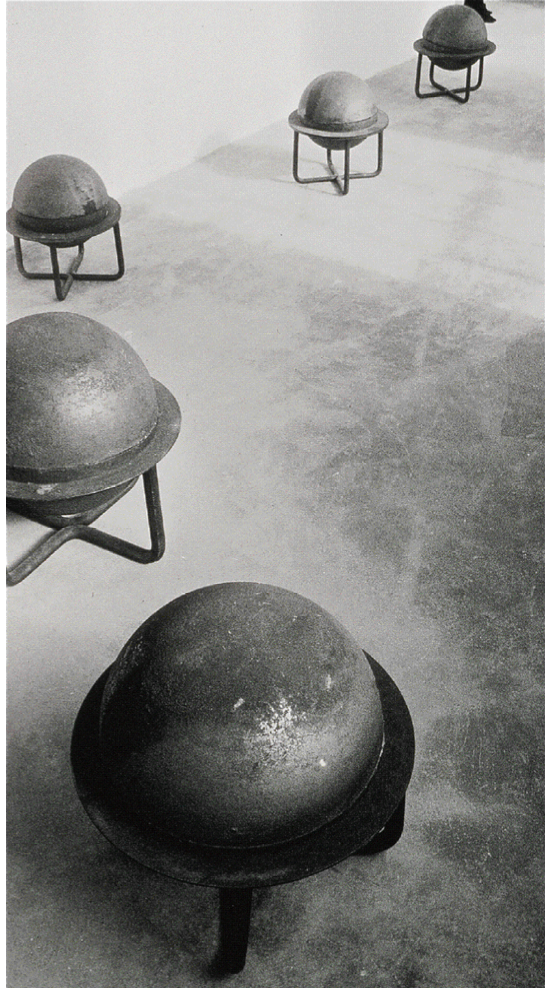

Somehow this seems like what would happen if you persistently took the long view of things. Maybe that’s why, from the long view, an icon of forward-looking modernist furniture design will seem antiquated, rusted. And maybe that’s why, in 1987, Gaman turned to making globes, literally “iron-bound,” as well as featureless. You need a distant perspective to see the world whole. These worlds, saturnine, and in fact ringed, are more often than not shown in pairs and are as flinty, stony-eyed, and blank as the orbs of blind Tiresias. Would it be fanciful to say they apply the seer’s doom to world affairs? Perhaps. After all, the globes are emphatically simple shapes, suggestive rather than specific. But what of that other, most recent curve? This time so small a segment of so large a circle as to appear almost flat. Christopher Columbus! Four of these were under way before Gaman’s untimely death, made of thin cast aluminum, a metal, but lighter. It is as though to be farsighted and so able to see the world as a whole is to be philosophical, historical, but iron-bound and reductive; to be nearsighted, peering so closely at only the smallest of areas, is to be IN IT, phenomenological, experiential, but also astigmatic and distorted, like so many of Gaman’s printed black circles. Near and far, of the moment and of history—this dialectic consistently informs Gaman’s enterprise. And so most recently he was scanning old drawings and printing out a few pixels to heights of seven or eight feet (the results, however, are far from pixilated). He was appropriating corporate logos and ads from the business section of newspapers featuring images of infinity in the form of endless water or sky, tilting them, of course, to skew the perspective. In a “purpose-driven, achieve-ment-obsessed” world, Gaman’s economy is spartan. Deadpan. It’s a little like hearing this phrase come out of Lloyd’s straight, affectless face: “Jeepers, creepers where’d ya get them peepers?”

INSTALLATION AT LONGHOUSE RESERVE, EAST HAMPTON, NY, 2012. UNTITLED, 1987, CAST IRON AND STEEL, 22 × 20 INCHES EACH, OVERALL DIMENSIONS VARIABLE

Gaman was self-effacing to a point rarely encountered, especially in the art world. That that world, now so completely immersed in its own special robber-baron era of plunder, should be so shortsighted as not to be able to “see” such an extraordinary artist as Gaman simply because he was incapable of making a spectacle (except his own cracked comedic renditions) is a sad paradox, given Gaman’s emphasis on the kind of attention and discipline necessary for “seeing” anything. One of his poignant worries was that his work was “not crummy enough.’’ Well, no, it is not crummy. It puns on the connection between being blindsided and being blind. But some of us are not blind. This is an elegant, fierce, rigorous, funny, and smart life’s work by an artist of the most intelligent consistency of, pardon the pun, vision.

Brian Gaman’s Wavelength

by Fintan Boyle

So the hope is that the work is both engaged and aloof.

—Brian Gaman

The work Brian Gaman made public—reticently so, it could be noted—centered on his production of sculpture and, more recently, large-format photography. The photographs maneuver their way around degrees of legibility, and opacity. They squeeze large amounts of digital information in and out of large territories of paper. In doing so they stage a problematized relationship between the image and the world the camera is pointed toward. One backstory to much of this work was Gaman’s immersive, though highly selective, interest in film.

In writing about Gaman’s work, my point of departure was to delve into the texts, occasional written pieces, notations, and journal entries where it was his habit to often directly address film. My thought was that in his writing some element of the cranky intellect that guided his choices in film, and also shaded his sculpture and photo work, would surface. The intellect was always sharply there in the work, of course. But the cranky edge, it seemed, was smoothed over by the cool to austere sheen of photography and the implacable, gnomic presence of the sculpture. Crankiness for Gaman was analytical—an interrogative mode. Perhaps crankiness needs to be caught on the run, relationally, in exchanges between people, or between people and their journals—in what they say.

Sifting through this material, the first title that caught my eye was “AGAINST BRROKLYN.” It seemed perfect. The spelling was everything—intentional, surely? A sly censure of hipster Brooklyn? But alas, when I opened the document, there it was: “BROOKLYN.” Gaman knew how to spell-check after all.

The text is short, drily funny, an almost-joke. Gaman leads you in, sets it up as if he is going to do the genre straight: “A guy walks into a bar”—almost. A Polish joke—nearly. But it is also (sort of) about interloping Californians, sunny Californians visiting the unsunny, ethnic neighborhoods of Brooklyn. It has the self-consciousness, the meta-dialogue, that defines his work. As one reads the “joke,” the sort ofs and almosts pile up and then the whole thing trails off into a non-territory. It becomes something we don’t recognize.

The story of the wood block. I know this guy who had a greenpoint [sic] studio. This story that he and his wife more than twenty years ago go to a Polish restaurant oil cloth and fluorescents and see this guy at the next table after eating alone gives the waitress a block of wood and no money to settle things up. The guy says I don’t know what kind of sense this story makes but about five years ago he and his wife take visiting California friends to a sort of new (bistro) candlelit in greenpoint and when the bill came he asked the young waitress if the tab could be settled with a block of wood. Something about the difference. Maybe the light.

As I have already noted, the piece is titled, in correct spelling, “AGAINST BROOKLYN.” However, the piece also has what one can only consider a subtitle: “With apologies to some acknowledgements to some.”

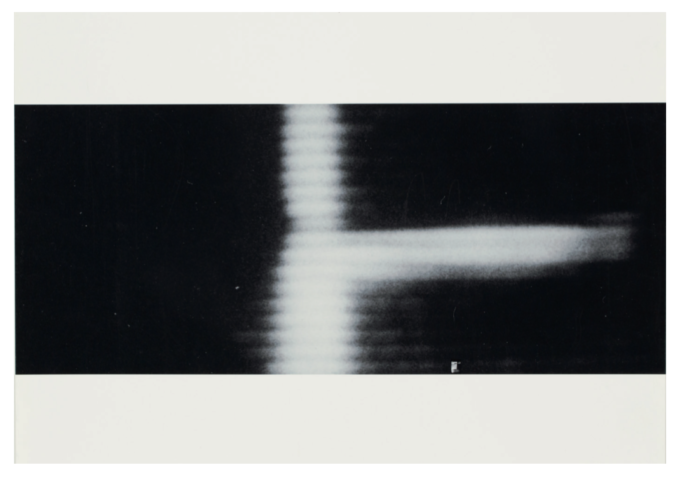

Let us remember that sometimes one apologizes and sometimes one acknowledges. Atop the page of “AGAINST BROOKLYN,” seizing half the page, in fact, is an uncredited, unidentified, unacknowledged photograph. Black-and-white, it shows an interior space, a loft space with tin ceilings, wood floor, and four large sash-hung windows along the far wall. The image is instantly recognizable to anyone versed, as Gaman so thoroughly was, in 1960s avant-garde film. It is a still from Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967). Wavelength was the film that stationed itself at the boundary of what cinema can be, the film that polemically challenged one to recognize it as cinema.

In Wavelength, so much is happening when nothing appears to be happening. Over the course of forty-five minutes the camera slowly zooms in at a lazy dawdle toward the wall of windows we see in the uncredited photograph in Gaman’s text. As the camera zooms across the eighty-foot length of that 1966 loft, it dismantles the formal, thematic, and conventional world that classical narrative cinema spent the preceding seven decades building.

A lot happens in Wavelength—a burglary, a murder; it is almost a policier, a cop show—its just that we are not directed to see any of this content as the prime focus. Rather, we must pay attention to the relentless grinding, the formal operation of the camera. Snow’s camera will not be distracted from its duty by mere narrative incident or trivial content. The aforementioned events of the film collide with that relentless camera movement, but the camera will not pay these “events” any mind. It just continues on its driven course. In due time, the work of the camera is done. The zoom, the formal operation, arrives at its terminus, the oceanic far wall of the loft. Wavelength closes on a photograph casually affixed to what was that far wall. It is a photograph that shows little or much, it is hard to say. One could imagine it having been the material for one of Gaman’s own photographs because of how much information it simultaneously provides and elides. Not a photograph of a block of wood exactly, but kind of close. The photograph offers the enigmatic presence of an unidentified ocean, waves breaking near shore.

Gaman’s recent photographic work is layered in the history of his studio practice. (For many years his studio was a loft like the one in Wavelength.) Scavenged fragments, burrs off the studio floor, crumpled beer cans, “old bits of drawings and other stuff saved for no good reason.” The stuff you might idly pin up on the studio wall became the material, the starting point for what would become Gaman’s large digital images. He wanted, in his words, to make images “that don’t look like much . . . in an effort to make current digital media push against itself.” Or to put it another way, Gaman wanted to push against the easy verisimilitude of digital rendering—to make things unrecognizable.

In another text, earlier, from the 1980s, Gaman poses a thought from his intellectual archive of the “Anxiety that there might be nothing to say?” (And he adds—very meta—“Weren’t we all supposed to be reading Baudrillard back then?”) And speaking of his earlier sculptural work, he finds it “scuffed, scratched, dusty and soiled”; “crummy, degraded looking works . . . a take on the decay of minimalism. A take on the world as fallen.” So it is not just a crumbling patina that seduces him, that brings him to a pause around this work, these images and films. It is the fact of a fall. Our postlapsarian fate in an art world where we fear there is nothing to say.

But then, what if there was no anxiety about there being nothing to say? What if saying very little was the proximate truth of mid-century contemporary art? There was, I felt, always in Gaman’s work a cranky disappointment that Minimalism, modernism itself perhaps, had failed, fallen. Minimalism was a strangely Edenic moment erupting in mid-century (though doubtless the history of modern and contemporary art could all be seen as a history of proposed Edens) that then fell or was banished to the theatrical.

In another journal entry, Gaman invokes Snow’s masterwork of 1971, La région centrale. This is Snow’s film of landscape as untrammeled but unwelcoming Eden. Shot over a period of five days in rugged northern Quebec, the film sparsely records the minimal operations of a mechanized camera in remote terrain as it obediently rotates through 360-degree pans in all directions, rendering the landscape as a three-hour narration without narrative. Gaman invokes the Snow film to cudgel or perhaps soothe the “Anxiety that there might be nothing to say?” He is soothing (cudgeling) artists who project on the landscape what Snow’s film refuses to find there in its unabating scrutiny. I think what Gaman was onto in the writings, the insight he had hit upon as he meandered around a landscape of fractured cinema and broken studio practices, was that poetry is, if not after all, impossible, at least sometimes hard to pin down.

I wonder, then, what Gaman made of Snow’s endgame in Wavelength. Of the way Snow scavenges—without apology or acknowledgment—an image of poetry from the ruins of a narrative cinema he has just destroyed?

For his part, Gaman pulls apart the soul and brain of photography, its capacity to faithfully render the world placed before the apparatus. Having done so, he ends up with a potent quotient of visual pleasure as large expanses of digital marks accumulate into strangely beautiful surfaces scavenged from the ruins of the studio. Gaman was perhaps a tenant in the late modernist moment of verisimilitude’s final bankruptcy, and as such I don’t think he was proposing any of this as a form of ontological truth. More problematically, it is simply the corner that history has photographed or filmed us into.

BRIAN GAMAN’S WORKS: THINGS NEVER DIRECTLY ENCOUNTERED

by Saul Ostrow

Although this text may try to explain too much, I think Brian would have liked its brevity. He liked things to be succinct—almost to the point of being terse. He was not concerned with the anecdote, the metaphor, or analogy. He instead privileged conclusions, yet he did not find it necessary to explain his reasoning or intentions. He also had a wry sense of humor; one always sensed that he was amused—by what? No one was ever sure.

The works that Brian made were visually simple things. They were reductive, enigmatic, and appear to be relational. They seem to be supported only by the aesthetic framework that guided the organization of their materiality. Yet, regardless of medium, material, mass, scale, or process, his works are contradictorily rigorous, delicate, considered, and capricious. While the results are often casual to the point that they verge on appearing to be found objects or readymades, they are recursive and discursive. As such he should not be thought of as a minimalist or a formalist, but as a structuralist.

As you will note, I represent my subject as “Brian’s works”—which refers to the products of his thinking and making as well as his oeuvre. My reason for not wanting to call what Brian made “sculptures,” “artworks,” or even “pieces” is that this would bind them to a discipline, a category of objects, and a history that I believe he sought to escape.

Brian’s works are not about objecthood. They can best be described as things, which by means of their index-ing reveal their complex nature. The diverse things Brian made constitute a form of presentation rather than representation. Despite the literal nature of what he made, his works function as puzzles, meant to be thought through. In turn, he puts his work before us as things that may be of interest.

His degree of personal investment and commitment to each project was in keeping with his personality, ethos, and aesthetic. In turn, it took Brian an inordinate amount of time to get his works right, because of the degree of technical and conceptual comprehension that each entailed. These works served Brian as a way to delve into the work (labor) of art.

The indexes that can be compiled from his works are peppered with facts, ironies, paradoxes, and a perverse sense of space/time. From the inconsistencies of these indexes, it is apparent that Brian’s works operate within multiple zones. The differing fields in which Brian’s works operate serve as lenses that amplify differing nuances and absences within and outside of each work. The boundaries between these zones are infinitely porous, resulting in their diverse qualities that mingle and form hybrids. Because of this, the qualities imparted by each zone lose their discrete identities. The melding of the varied zones that Brian’s works are to be found within can be likened to Marcel Duchamp’s idea of the infra-thin, which denotes those differences, or elusive intervals that define shifts in the states of a thing’s being.

The infra-thin as an interface cannot be perceived for the characteristics of transition from one thing to another are similar to the boundary between warm and cold bodies of water. Like the infra-thin, Brian’s works represent a moment of instability or uncertainty characterized by heterogeneity and mutability. Each work, in its own way, blurs the boundaries between multiple states of being. These may be thought of as comparable to the difference between a clean shirt and the same shirt worn once, or the lingering taste in one’s mouth of smoke that has been exhaled. Consequently, as things they do not coalesce into cogent objects, but are defined by a set of conditions.

Like the doors, windows, piping, light switches, et cetera that make up a house, Brian’s works might all be thought of as “in-between things,” in that each can be isolated, but when they are serving their function they lose their identity as discrete objects. This dominion of uncertainty and transition is what Brian sought to make palpable by converting the interstices between things into tropes. In doing so, Brian’s works mark the boundar-ies of the attenuated territory from which viewers posit with certainty that the thing before them is not “this” or “that,” while in the same moment they are not able to assert definitively what it is. It is the forever unknown and indeterminate space of the viewer that Brian’s works make tangible by emphasizing the indeterminate nature of perceived reality. Brian’s work asserts that what we experience is in all ways merely an approximate “model” of a world we never directly encounter.

As with Duchamp’s Large Glass, by joining and separating things from the space around them, Brian’s works serve as a portal—an opening onto the undefined space of potentiality, where presence exists “beneath” per-ception. This is the real that haunts us, that space where things happen without reason or logic. By producing an “uncanny” simulation of the real, Brian’s works paradoxically bring us closer to an understanding of reality as something based on a restricted amount of sensory input and data, which, in our isolation, we come to imagine we are capable of comprehending.

Caught in the flux between losing their virtuality and becoming fixed objects, Brian’s works, by implying that the passage from one state to another is always taking place, articulate transitional spaces. So, if they are about anything, Brian’s works are perhaps about the process of discerning how one comes to acquire information about things. This destructuring of the idea of the thing-in-itself, having a prior fixed meaning, in turn seems to reveal that the “work (labor) of art” is always contingent on the conditions of its reception. From this, we may speculate that Brian’s ambition was to afford those who engage with his things an ability to view themselves and the world a little differently.

INTRODUCTION

by Terrie Sultan

Brian Gaman conceived the territory of art as the contradiction between the physical world and our shifting attempts to define that world. Like Knausgaard’s concept of the “vanishing point” in humanity, Gaman’s creative process strove to demarcate the distance between reality and our perception of it. His wife, the curator and artist Bonnie Rychlak, describes him as “a man of few words,” and it is true that he wasn’t particularly effusive when speaking about his art. His approach, which combined Samuel Beckett’s oblique theatricality with the rational simplicity of 1960s Minimalism, can be seen in his writing, which is punctuated by statements like “No one has seen it before and no one will see it again. No one thinks it is dystopian and no one thinks it is inevitable.”

Yet lest we think of Gaman as a reductive existentialist theoretician, it is important to realize that his artistic production involved not only sculptural and photographic media but also his own innovative design and subsequent construction of his Springs residence and studio buildings. I was introduced to Brian in 2008, shortly after I became Director of the Parrish Art Museum. Although we occasionally met socially and talked during several casual studio visits, it wasn’t until 2013, when Brian was selected by Keith Sonnier to participate in the Museum’s Artists Choose Artists exhibition, that I fully recognized the clarity of his reductive approach to art-making. Gaman began making art in the mid-1970s, embarking on a highly personal exploration of the nature and process of perception, which became a sustaining theme throughout his career. One video from this period tracks the perspectival diminution of a man running away from the camera until he shrinks into a tiny dot on the horizon, a notion of diminishment and disappearance that recurred more than twenty years later in Gaman’s large-scale works on paper. By the late 1980s, he had moved into the rough physicality of object-making, creating sculpture that reshaped industrial cast-offs into intricate, almost magical machines. These mysterious untitled objects, materially and compositionally minimal, did in fact refer to the real world in form (especially eyeglasses), but were imbued with suggestive observations about the nature of perception.

From the late 1990s until his death in 2014, Gaman experimented with photography. Working outside the medium’s mainstream representational tendencies, he expressed himself in two dimensions by mining older work for images, digitally scanning them and enlarging them massively until the image deliquesced into an unrecognizable, atmospheric expression. Pioneering modernists such as László Moholy-Nagy and Aleksandr Rodchenko proposed similar uses for photography, with more concrete imagery as their starting points, but Gaman’s near abstractions, enigmatic and evanescent, question our reliance on photography as a means of understanding reality by fixing an approximation of everything we can hope to see, from a comet in space to a subatomic lattice structure, even as we realize that those images do not convey the totality of what they attempt to depict. Similarly, Gaman’s large-scale works suggest that emotionally compelling meaning can be teased from the simplest of visual gestures, even as recognizable images grow fleeting and unknowable, like physical form shrouded in mist.

The essays above were originally published in the catalog for the exhibition, Brian Gaman: Vanishing Point, at the Parrish Museum in Southhampton, New York.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Parrish Perspectives is conceived as a series of concentrated exhibitions that offer the Museum opportunities to respond spontaneously and directly to unique ways of thinking about art, artists, and the creative process. We are proud to have the opportunity, in Vanishing Point, to explore more fully the broad trajectory of Brian Gaman’s work. Although he left us too early with his unexpected death in 2014, his artwork and intellectual acumen remain as his legacy.

Brian Gaman: Vanishing Point would not have been realized without the dedication of many individuals. We acknowledge with much appreciation the enthusiasm and sponsorship of the Leadership Committee, whose generous support facilitated the organization and presentation of this exhibition and accompanying publication: Elizabeth Segerstrom, Lionel Sanders and Teddi Berger, John Alex, Claudia Camozzi and Terry Kemper, Susan Dunne / Pace Gallery, Bob and Lynn Lipman, Linda and Steven Miller, Shoji and Tsuneko Sadao, Nicholas Sands, Amy Wolf and John Hatfield, Dietl International, Natalie Gliedman, Rachael Horovitz, Robert Sundheimer, Barbara Starr, Leah Sanders, and those who wish to remain anonymous. We deeply value the public funding for the Parrish from Suffolk County. The Museum’s programs are made possible, in part, by the New York State Council on the Arts, with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, and by the property taxpayers from the Southampton School District and the Tuckahoe Common School District.

We are especially grateful to Bonnie Rychlak, who worked for more than a year to organize and catalogue Brian’s entire oeuvre in order to make the full trajectory of his artistic career available for study. She has shared her insights as a curator and artist in contributing to this undertaking. This partnership was enhanced by Eileen Boxer’s sensitive approach to the conception and production of this book, and her generous support in contributing her design services. The essayists, Fintan Boyle, Saul Ostrow, and Jeanne Silverthorne, have illuminated Brian’s creative process and provided diverse pathways for understanding his work. We thank Anna Jardine for her copyediting.

At the Parrish, members of the staff worked diligently to bring this endeavor to fruition. We are indebted to Alicia Longwell, Lewis B. and Dorothy Cullman Chief Curator, Art and Education; Registrar Chris McNamara; Preparator Robin Klopfer; Curatorial Assistant Michael Pinto; Andrea Grover, Century Arts Foundation Curator of Special Projects, and curator of the 2013 Artists Choose Artists project; Director of Communications Susan Galardi and our colleagues at Fitz & Co.; Cara Conklin-Wingfield, Education Director; Scott Howe, Deputy Director for Administration and Institutional Advancement; Eliza Rand, Associate Development Officer for Foundations and Major Gifts; and Barbara Jansson, Administrative Assistant—all of them indispensable in the realization of Brian Gaman: Vanishing Point.

Finally, we acknowledge with profound gratitude the Parrish Board of Trustees, under the skilled leadership of Fred Seegal and Peter Haveles, whose confidence and encouragement allow us to pursue such ambitious projects.

T E R R I E SU LTA N