Fariba Hajamadi

Fariba Hajamadi has been involved with making photographs for more than three decades. Her Brooklyn studio, the place where she currently works is also the site of her back catalogue. On a daily basis she confers with this sedimented archive of photographic technologies and histories that have shaped her studio practice.

Making, as in manufacturing, crafting or fabricating, is so often the invisible piece of photographic work. The photograph on the wall, or on the page, more than any other artifact of cultural production unobtrusively conceals its having been made. It seems to just present a yonder ‘there’ to us. Ever more so is this the case with the machinations of the digital image-world where the work done, in Photoshop say, can be seamlessly slipped past our reality testing antennae. And, in an age when it seems one can digitally print, with ease, any image to any size on any surface, it is hard to remember that until quite recently to produce a large format photograph meant you either paid through the nose at somewhere like Duggal or you jury-rigged the whole operation yourself.

In the early 1980s Hajamadi would, to produce large format photographs, work through the night (no light) in her blackened-out loft in pre-fashionable Chelsea. Vats and trays of chemicals, ranging from large to enormous in size, lay on the floor and saturated the space with fumes. For flexible, unstretched canvases the method was to roll them through the large trays of chemistry while larger wooden panels, up to four by eight foot, would be laid in trays built to fit. To print on such panels and canvases Hajamadi would prepare them with a liquid photo emulsion that could be painted onto porous surfaces. After a great deal of test exposures and dodging and burning Hajamadi’s hands would caress the image into being by washing the chemicals across the prepared surface in the morbid Halloween glow of a safe-light. It was all a very messy, physically taxing, hands-on process.

These days on the lower level of her double decker studio she produces all the work digitally from an array of screens, laptops and plotter printers. The redundant technologies, old cameras and enlargers, accumulate as their own ironic museum collection.

Throughout, from the creaky Chelsea loft to the Brooklyn duplex, Hajamadi’s endeavor has required her to make a reflexive turn and to observe herself as the observer, the spectator. In this there is an examination of how we as spectators are guided to see, read and locate cultural knowledge. Her practice, her research mode, is to stroll the aisles and corridors of museums photographically recording their artifacts, their spaces, their modes of display and their architecture. Hajamadi has done this across the board. From encyclopedic to specialist museums, she tirelessly catalogues the already catalogued. In this there is an examination of museum culture, an enquiry about the choices made, the histories told and also the ones not told. Thus it is an enquiry about how the museum’s spatio-temporal organization under scrutiny renders a series of omissions and blind spots as well as a series of representations.

In effect the viewer has turned the prerogative and authority of collecting on its head, i.e. Hajamadi, the viewer, does the curating, and the de-accessioning. While back in the studio Hajamadi, the artist, then works to make literal cracks or fissures appear within the spatio-temporal continuity that she has just been trawling through in the museum.

Her hands-on process has long relied on collage and image manipulation. Both processes, previously executed, in fact, by hand—cut and paste and then cautious airbrushing of the images retrieved from museum visits. Nowadays it is all digital. Thus photographs of museum artifacts, displays and architectural features are assembled into, in the earlier instance, a hand made maquette to be re-photographed to make an inter-neg. While, more contemporarily, the images are PhotoShopped into Hajamadi authored dalliances with one another.

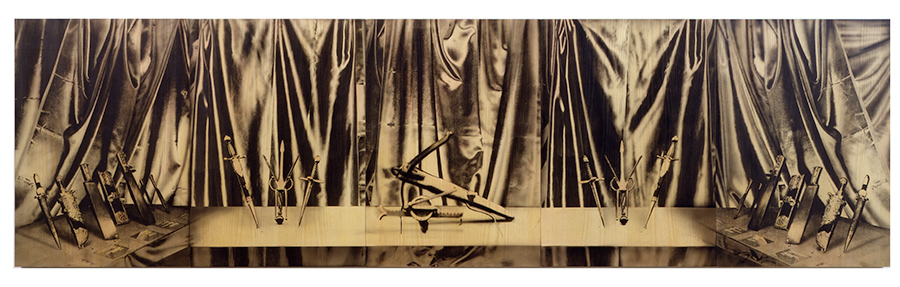

Often a collaging of sorts has also shaped the final presentation of the work. Images will be presented, or installed, for example, as suites of large panels. In Until the End of the World, 1991, two four by eight feet wood photographic panels lean, as if bodyguards, against the wall on each side of a wall-hung three by six foot panel. Or in a more complex reinvention of the museum space itself, in a 1996 installation in the entrance of Neue Galerie in Graz, Austria, Hajamadi contorted the iconographic logic of the museum space with wallpaper, of her own manufacture, titled Rape. The wallpaper bore images borrowed from Goya’s Disasters of War and Käthe Kollwitz drawings of war victims.

Hajamadi‘s collage has never relied in the sort of hard, declarative juxtapositions of early Dada, such as Hanna Hoch. Hajamadi’s assembled images, instead, tippy-toe back toward the look and feel of the seamless spatio-temporality of both photography and museological discourse while, quite deliberately, never getting there. Thus it can be said that her collage practice deliberately looks as though it is going to restore or be faithful to the logic of seamlessly rendered space that is photography’s signature. But, by not quite getting there, it is as if seamlessness is restored and undone simultaneously. At the last moment or perhaps better put, at some unanticipated and unnoticed edge within the visual field, it becomes apparent that this is a hand made space. It becomes apparent that the photographic scene one is looking at does not have a single corresponding referent —a ‘there’—in the world beyond. In turn it is made apparent that the taxonomic scheme of the museum is not transparent and natural. Simultaneously the made-ness of photography and the made-ness of the organizing discourse is revealed. In this stirring of the historical and ideological pot —or plot— gaps and cracks are exposed in the baton-passing continuity of represented history. Importantly, the museum-as-knowledge-machine is never entirely undone, that is not the purpose, indeed the museum’s look and feel is often mimicked, but its machinations are laid bare.

That she returns the objects, approximately, to a museum mode of display is then Hajamadi’s backdoor. Having stolen/borrowed the museum’s artifacts, she makes them her own, and in this act of vandalism, politics, or curatorial gall she mixes and matches from different institutions and cultures of display. We need to hold onto the recognition that the perceptual-cognitive dissonance that Hajamadi cooks up in collaging is subtle. Double and triple takes abound as cultural artifacts are re-displayed as cultural artifacts shoe-horned into conversations with one another, different than those in the authoritative museological discussion.

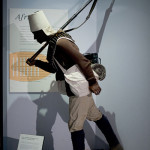

In a recent series of works where the collaging hand feels more restrained, attenuated, this presence of the museum chatter is given a ghostly presence. By simple adjustments in point of view, focus or camera position –the photographer, say, stepping a couple of paces to the left– she lets the official narrative trip over itself. These are all images shot by Hajamadi at the Imperial War Museum in London. Photographs of human scale mannequins dressed in the uniforms of various armies loyal to the British imperial enterprise. They are mannequins of British soldiers or of what were known as the ‘colonial troops’ —the natives of India, British Somaliland, Ireland, etc.— who fought ‘loyally’ for the Imperial power.

This series of Hajamadi’s photographs are printed on stretched canvases of around 3 x 4 feet size. In most images museum informational texts, wall labels and captions, are visible yet largely illegible. The text, or we could say the official context, has slipped just beyond the range of the camera’s focus. The feel is not of a treacly Vaselined lens exactly, more a Sfumato softening where the images’ edges are beckoned toward somewhere other than the museum’s plan. Through this ‘move’ we know there is an authoritative discourse with which to situate the tableaux we are seeing and we also know that Hajamadi has photographically escorted the mannequins away from it. The juxtapositions, from image to image along the wall, or sometimes within the image via reflections in vitrines or glimpses of other discrete objects in the background provide the collage-effect. The original tableaux are offered by the museum as a 3D simulation of a specific moment, as if they were a proto-3D print of history. However, absent the fullness of text, affiliations and loyalties are opaque. This soldier could be for or against, heading to the front from either side or indeed retreating. Indeed who is that soldier fighting for? In some images Hajamadi photographs the mannequins from behind, she turns their backs on us. Even the way of seeing, as anticipated by the museum, becomes un-guaranteed. The taxonomic logic, which brought all these soldiers together, already brittle, is now, with a pulled focus here, and sneak-a-peek from behind there, tilted off kilter.

To some extent Hajamadi’s entire project is another voice in the conversation about who is history’s author. Who can interrupt the speech-maker most often could be one way to think of her voice? But Hajamadi is intent on doing more than simply heckling the cultural archive. In her most recent body of work she has joined the tourists traipsing through the labyrinth of Pennsylvania’s Eastern State Penitentiary. Formerly a prison, the model prison of Eighteenth Century Quaker reform, the building is now a hugely popular museum. Designed and built as “a machine for reform” where prisoners were held in permanent solitary confinement the better to promote penitence. Hajamadi’s images offer a view in toward where each solitary prisoner would live. The walls are crumbling, a ruined monument to the changing face of cruelty. Shone down from above, within each image, is a hard shaft of natural light delivered by a single glass skylight. The skylight represented the “Eye of God”, suggesting to the prisoners, it was held, that in their total isolation, God would always be watching them. God’s sort of upside down panopticon indeed, though Hajamadi’s images reveal an architecture that would surely bedevil any occupant. The difference one feels with this body of work is, I think, all about the place. Not a former palace revolutionized into a museum, not a purpose built museum but a museum where the site itself is the object, container and contained all in one. More or less Hajamadi’s ally, the museum that looks back at itself.

http://www.faribahajamadi.com

Wonderful article.