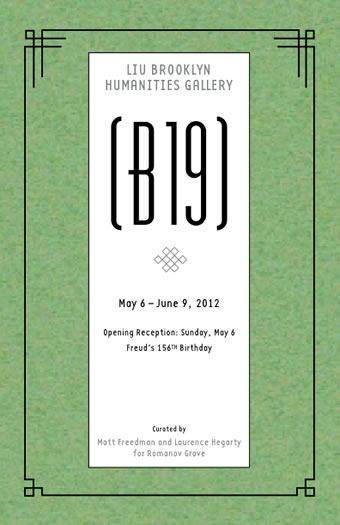

(B19) The Psychic Life of Objects

by Matt Freedman and Laurence Hegarty

Below is the essay which accompanies the exhibition (B19) at the LIU Brooklyn Humanities Gallery

May 6 – June 9, 2012

Download the catalog (pdf, 1.6MB)

catalog designed by Jennie Nichols

Read David Brody’s review of (B19) – Meth Lab of the Modern Psyche: Dr. Freud’s Consulting Room

Matt: I’m thinking perhaps my attachment to this show about Freud’s office comes, as is only proper, from still percolating issues with my late psychoanalyst father and from the strange family dynamical confluence of home, office art and furniture that animates my childhood memories.

In the middle of our apartment here in New York now is the therapeutic couch my father bought almost 60 years ago to launch his career in private practice. It was hardly ever used for its intended purpose after my family moved to Chicago. We had no furniture save four items from my father’s office: the couch, a liquor cabinet he used to house recording equipment during his sessions, his therapist’s chair and ottoman and a writing desk. The cabinet returned to its intended purpose, the chair became the centerpiece of the living room and the writing desk became a platform for houseplants. The couch moved around the house a lot and functioned as a kind of sofa manqué. I was sitting on it with my older brother watching the live television broadcast when Jack Ruby shot Lee Harvey Oswald. My brother jumped up and ran out of the room shouting, “I’m an eyewitness! I’m an eyewitness!”

Several years ago my partner Jude Tallichet made a bronze cast of the couch for an exhibition called Sub-Royal. There was some staining and tearing of the fabric of the couch during the casting process that we haven’t gotten around to fixing. At the moment it’s covered with books and papers. The mold for that piece is the basis of Jude’s contribution to (B 19). Family and coincidence are twinned themes that run though this show.

My father’s study on the third floor of our house in Chicago was filled with knickknacks and art works. In layout and density it evoked the images of Freud’s office as seen in the famous photographs taken by Edmund Engelman just before Freud’s flight to London. My father’s study had a fireplace at one end and on the wall above the mantelpiece was a framed photograph of Judge Learned Hand, a man my father greatly admired. They worked together on a revision of the Model Penal Code and the inscription reads, “With gratitude for light that a little penetrated much obscurity.” There were also a series of small prints he collected, including two long Chinese watercolors. Freud too had prints on his wall, most notably the one of Charcot ‘exhibiting’ a hysteric. And we know that it is in response to this print that Peter Drake has created his video for (B 19). My father also had many small sculptures on his enormous desk that fascinated me. The most interesting was a small plaster figure of a creature with the torso of a man, the head and webbed feet of a frog and the tail of a snake. It was painted to look like bronze, but one of its arms had been broken off years before, revealing that it was actually a hollow plaster casting. I’m not sure, but I believe it had once been part of a series of figures that when placed side by side executed a somersault. The catastrophe that had robbed the figure of its arm had destroyed the rest of the series entirely, making it possible for my father to purchase the single maimed survivor, I think.

Across the street from us lived the Morrison family. Kate Morrison, the mom, was the granddaughter of Carl Koller, a colleague and rival of Freud’s in Vienna. Both men were involved in exploring the uses of the new wonder drug cocaine, to which Freud eventually became addicted. While Koller went on to develop its use as an anesthetic Freud went on to hone his ambitions in psychoanalysis. Here, in (B 19) Koller’s great grandson, Bill Morrison, has made a film pondering their complicated relationship.

My father’s office at the University of Chicago was also filled with interesting things. Its geography was complicated, though I suppose probably not as complicated as Freud’s. My father’s office held several Persian rugs for example, while Freud had Persian rugs galore. In fact they seem to be a mainstay of the psychoanalytical edifice and for (B 19) Elana Herzog is employing rugs to remap the architecture of the psychoanalytical office that we are superimposing upon the gallery. Similarly, Natalija Subotincic has created architectural drawings for (B 19) that perfectly reproduce every object in Engelman’s photographs of Freud’s office. I imagine we could use Natalija’s drawings to locate evidence of Freud’s habit; the one that killed him that is, the tobacco, not the cocaine. But we need not, as this has all been addressed for us by Kyle LoPinto. Kyle has re-created Freud’s cigars for (B 19), presumably without metaphor, while Allan Wexler has supplied a work that evokes the chairs Freud used when writing his texts and when interviewing new patients.

My father often interviewed men accused of horrible crimes whose lawyers hoped to mount an insanity defense at their trials. Once when he was occupied elsewhere he asked me to administer a basic multiple-choice test designed to measure the baseline level of mental competency of a man who had kidnapped, tortured and murdered a young woman. The man, notably small in size and meek in demeanor, was led into the office in leg shackles and handcuffs by a huge cop who dumped him in a chair, unlocked the shackles and announced, “you have half an hour,” before leaving the room. I sat while the accused man tried to fill out the form on a board balanced on his knees while still handcuffed. Every few minutes his pencil would fall on the floor and I would track it down and put it back in his hands. I felt so terrible for being part of an operation that so humiliated another human being that I kind of lost sight of what he had done in the first place. I stared out the window and tried to imagine I was someplace else. Half an hour later the cop barged back in, and without even looking up slapped the shackles back on the prisoner and dragged him out to the van.

That was effectively the end of my career as a therapist. My father was a consulting psychiatrist for the trial of John Wayne Gacy, the man convicted of murdering over 33 boys in his home. My father said Gacy was the most manipulative individual he ever met. After his conviction and death sentence Gacy, trying his best to influence anyone he thought could keep him out of the electric chair, would send my family handmade holiday cards from prison. There was always a bland winter image painted on the front of the card with an equally innocuous note written carefully inside, “A Joyful Holiday to You and Yours”. On the back was a handmade logo: “Gacycard”. Slipped inside the card was another note on notebook paper; “Hey Doc, how’s it hanging?”

My father had been an amateur sculptor, studying with a professional named Franc Epping. Our house had a Polynesian style self portrait he had carved in wood, a plaster head of my mother he later cast in bronze and several oil clay heads that kicked around from table to table. I still have one. As a child I began attending ceramics classes at the Hyde Park Art Center and for years afterwards I brought home a steady stream of heads, figures, urns and plaques, most of which reflected my fascination with Greek and Renaissance sculpture. My parents approved of these figures. By the time I left for college all the windowsills were filled with them, and several shelves had been erected to hold the overflow. The plants on my father’s old writing desk had been pushed aside to make room for more pieces. Freud always seemed to find more room for his objects without losing his plants or incapacitating his writing desk. Rob de Mar has taken on the challenge of reincarnating the vegetation Freud lived with.

After my father died, in addition to the couch I hauled back to my studio the not- inconsiderable collection of plaques from his office. For several years I hung them on the walls in my studio as I contemplated their possible evolution into a work of art. I still haven’t figured out what to do with them, but as I recall, Laurence, you noticed the plaques during a studio visit and that initiated the conversation that eventually led to the (B 19) show.

Laurence: The plaques? Yes, I remember them. But I think I am now most moved by the image of you and your brother – perhaps others were there too, I do not know – ‘on the couch,’ as we say clinically, watching Ruby murder Oswald. It seems perhaps that your brother, the “eyewitness,” hijacked your memory-to-be the way Ruby hijacked Oswald’s 15 minutes. I wonder indeed how you feel about it, but I do not want you to tell me.

That your memory was ‘on the couch’ anchors our concerns here with this show, (B 19), in the aesthetic: the look, the feel, the texture -not the words- of the psychoanalytical encounter.

The couch is many things. Freud famously used the couch because he did not like to be stared at by his analysands. But I have always felt a certain disingenuity to that conceit. The couch is, at its best, the agent of psychoanalytical reverie; detached from the relational context of talking with another, one sinks into its texture and comfort, one’s body unfolds its rigors and muscles and thoughts freely associate – or so the theory goes.

Wikipedia, I have come to think, with its hypertext links, is also a mode of guided free association. I was inspired by your letter to dig a little on Ruby. And as you undoubtedly know he was, like yourself, from Chicago. He was a man with a past more checkered than yours or your father’s (as far as I know). He is alleged to have worked for Al Capone and to have been involved in corrupt union practices or perhaps in the practice of corrupting unions. Given what I already knew of him none of it was that remarkable. Then, trawling through a bio of his I came upon this,

“Jack Ruby left this job and found employment as a salesman. This included selling plagues (sic) commemorating Pearl Harbor”

What would you say is the most popular image of Psychoanalysis? Perhaps it is the couch? Quite possibly so; or maybe it is the analyst’s beard, or cigar. I really don’t know, but surely somewhere up there is the parapraxis! The Freudian slip!

I want Ruby’s sale of plagues to rhyme somehow with those plaques from your father’s office, with the ceramic plaques, with the ‘steady stream of heads, figures, urns and plaques’ that you brought to the family home as a child. I imagine the eager proto-artist in you cluttering the home with your collection, aestheticizing the family scene with curios and adolescent meanderings upon classical culture.

There is a strange tale, most probably entirely untrue, spun by Lacan about Freud and his cadre as they were arriving in New York for that lecture series at Clark. (At the end of which journey the Boston neurologist-psychologist James Putnam gave Freud a bronze porcupine for his collection, and now Putnam’s great-grandson George Prochnik has contributed to (B 19) a mad monologue from that porcupine, whose image is in this very catalogue). Jung reported to Lacan that in 1910, as he, Jung, sailed past the Statue of Liberty with Freud at his side, Freud turned to Jung, half glancing back at the great statue and said, “They do not realize we are bringing them the plague.”

A plague upon the American house of psychoanalysis is the subtext to Lacan’s fictional trifle. But nonetheless this recurrent motif of the plague come plaque intrigues, does it not? What would Ruby have on his own memorial plaque? What would Gacy want on his?

Your father might of course have suspected complete untruth from John Wayne Gacy. Or perhaps better put, one might expect a series of masks; masks like those manipulating holiday cards. In one sense to imagine those cards from Gacy is silencing: breathtaking. And then I imagine that hand drawn “Gacycards” logo; turning so deftly, so creepily upon a notion of the unconscious of Hallmark. All of this is perhaps to say that the aesthetic – the face of the card as much as the legend inscribed within, the plaque as much as what it signals – is as important as language in the shrink’s office.

And so I suppose we have asked our 19 artists to explore the psychic life of objects. We have asked them to ruminate upon Freud’s knickknacks, his antiquities, his rugs, pictures, tchotchkes and chattels; we have asked them to toil diligently in their studios because we know that the aesthetic expresses the unspeakable.

I mean why is that extra detail, the aesthetic detail, “as we sailed past the statue of Liberty” needed in Lacan’s tale? Because Freud’s alleged words bounce off the great aesthetic gift of the French people to America. Similarly I imagine the analysand’s words ricocheting off the clutter of Freud’s or your Father’s overstuffed office. Did you know Freud was inclined to show and tell the figurines to the patients, at least by HD’s record he was. And surely thus he inserted them in the patients’ thinking: into their analytical ramblings. Athena was his favorite he confessed to HD. Athena the Goddess of “wisdom” and, among other things, “Just Warfare”. When HD bends to pet Freud’s beloved chow Yofi -despite Freud’s express instruction that she not touch the dogs- is Athena her secret ally?

So here we, you and I, have Matt Blackwell diligently toiling to reincarnate the chows -parent and pup- which probably won’t bite but I’m betting their shaggy coats have lice. While Joe Amrhein renders his version of the plaque that adorned the Herr Professor Dr’s door at Berggasse 19. The plaque that gave entré to, or concealed, depending upon your point of view, what lay within.

And, appropriately perhaps, we do not even know what half of the artists are going to produce for the show -we simply know their starting point, the Freudian artifact they began with. As with free association, we do not know what is coming next, a hostile yelp or a benign and tender eulogy. Jane Irish is reconfiguring Freud’s Urn. That urn. The one he is still in. The one that sat in his office for many years and in which his ashes are to this day interred. We know too that Peter Kreider has made a version of the Roman citizen’s bust that stood behind Freud’s analytic couch. We know too that unlike Freud’s bust, Peter’s is motorized, miniaturized and spins.

And we know that David Humphrey is busily reifying the visual layers of horizontal and vertical spaces in the office and kitchifying Freud’s antiquities. So mysteries are going to unfold as the work is delivered.

Yet the rhymes and echoes are all there: Freud, your dad, your chairs, tables and manacled men. And you know the chair Francis Cape is making for us for (B 19), that is the chair that would be equivalent to the one you sat in to interview the manacled man. And now it rhymes too with the chair Freud sat in to listen to disconnected fragments from the discontented bourgeoisie.

Yet it is through all this clutter that the analyst’s office becomes filled up with thoughts, actions and ideas that circulate in the exchange between the participants. Things get said and even if they are not particularly fragmented the analyst’s mode of listening fragments them. This, what the patient just said, is not necessarily true or false, we tell ourselves, instead this is the way the patient needs to organize, to present, what he tells us – i.e. it is the analysand’s way of aestheticizing. So turn that around. What is the analyst Freud telling by the way he needs to organize his aesthetic display? What is your father telling us with a Polynesian style self- portrait or with a small plaster figure of a creature with the torso of a man, the head of a frog and the tail of a snake?

So are we back in the office yet? Our office of (B 19) that is; back with a bunch of New York artists riffing upon Freud’s aesthetic choices on the occasion of his 156th birthday? Jude, you tell me, is casting your dad’s couch again. This time it will be pink? Jennie Nichols has refigured the antiquities collection in wax: but this time Easter bunnies cavort with Catholic priests and frogs: don’t ask. We have no one to blame but ourselves. We have asked them to explore the psychic life of objects. We have asked them as artists to ruminate upon Freud’s antiquities, geegaws and doodads; we have asked them to toil diligently in their studios because we know that the aesthetic speaks the ineffable. And if the whole affair of (B 19) reminds one of a wake I imagine Jeanne Silverthorne’s dead rubber light bulb will cast a suitable mourning shadow over the whole affair. This is appropriate, psychoanalysis has been pronounced dead more times than painting has.

I am drawn, again, by that comic image, the memory of the two brothers watching TV and history unfold from the analytical couch, to ponder where do psychoanalysis, history and aesthetics collide? Memory makes stories. What are we to make of the Morrison family lore of Oedipal victory over the great man himself? In (B 19) we can turn a glance, through Bill’s film, to the now empty edifice of psychoanalysis’ invention. While in a perverse return we shall scrutinize Berggasse 19 being looked at through the transparent glass walls of the LIU gallery. It puts me in mind of you, staring out the window of your father’s office to avoid looking at and being seen by the manacled man. That puts me in mind of Jonggeon Lee’s windows. The reconstructed windows of Freud’s office at Berggasse 19, rebuilt for (B 19) and through which we can all look at the work of the other artists in the show. Framing and veiling has evolved, doubly, as a motif of the show and as a means to address the architecture of the gallery. Thus it is good that the most substantial stab at architecture in the whole of (B 19) comes from Letha Wilson. She is building the walls to blind the glass walls of the gallery but also to literalize the archeological metaphor that Freud so loved. Ripped apart -yet left to stand- her walls are manufactured from used and discarded sheetrock and studs. The past is thus restored in a reworked form.

You know Matt, with Natalija’s drawings we could of course have recreated the office as-was. Right down to the floorboards. But that would be mere verisimilitude: a hideout at best. Much preferred then is the aesthetic reverie over the genuflection, the artist’s interpretation over the manifest: the hidden rather than the offered.

Matt: I think Jude’s new couch is red, not pink. One last family and coincidental theme to throw into the pot – just a few weeks ago my old neighbor and (B 19) contributor Bill Morrison brought his friend, the writer Lawrence Weschler, to my studio. When I happened to mention this show in passing, Weschler, a master of serendipity and convergences, blithely mentioned that he was a distant cousin of Engelman, the photographer whose work provides (B 19) with many of its visual cues to Freud’s office. After allowing me an appropriate gasp, he calmly continued, “I can top that. Engelman’s son Ralph is the head of the Journalism Department at LIU.” And so he is. We are most grateful to Ralph, who has contributed an original print of one of his father’s photographs to promote this exhibition. One last, smaller coincidence I forgot to mention to Mr. Weschler, but I have to get it off my chest. The cousins, Lawrence and Ralph, were brought together when Lawrence won the prestigious George Polk Award for journalism, which is presented by Long Island University. The award named for a correspondent killed during the Greek Civil War in 1948. George Polk’s surviving brother, William, lived across the street from our house in Chicago, directly behind the Morrison’s.

Laurence: A red couch! This is unheard of in the analyst’s office, and is thus an excitedly anticipated perversion. But you are right; all these circulating coincidences around your home hearth in Chicago are riven through with layers of weirdness upon weirdness. In His essay, The Uncanny, Freud’s German word is translated, as the title has it -“the uncanny”. But there is a lengthy passage pointing out that the more accurate translation of his German would be “unhomely”. Freud’s essay is in the end a rumination upon how the homely is that which is familiar and known, but also, simultaneously that which is hidden from view, that which is masked and unknowable.